Figure

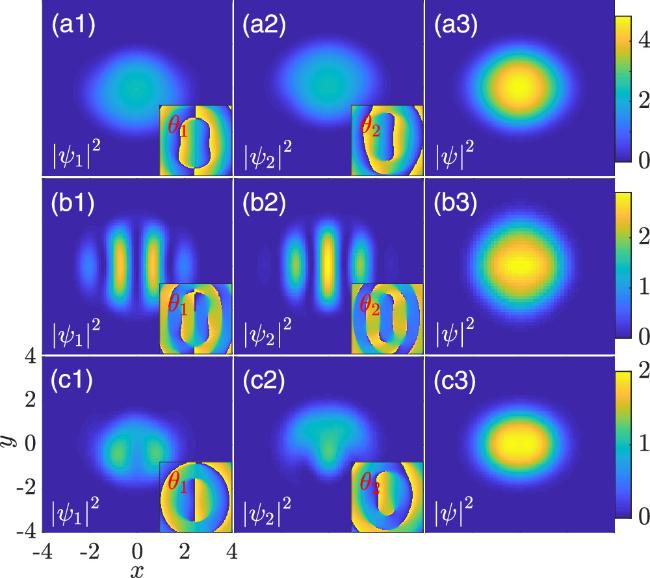

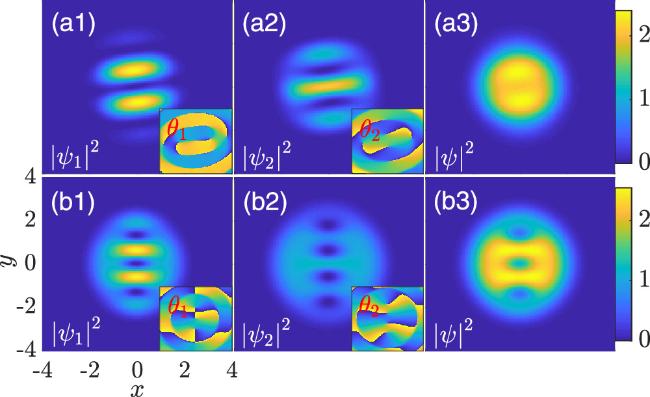

1(a) illustrates the PW soliton when

σ1 >

σ2. In figures

1(b)–(c) the density of each component exhibits a stripe structure, while the total density does not. Analysis of figure

1(a1) and (a2) reveals that the upper component of the soliton is slightly larger than the lower component. Subsequent examination of figure

1(a3) demonstrates that the total density of PW solitons is presenting a Gaussian shape. Figures

1(b)–(c) display the stripe solitons when

σ1 =

σ2. In these cases, the densities of each component exhibit a stripe structure, while the total density does not. The number of two-component stripes increases with

β, and the upper component consistently differs by one compared to the lower component. The stripe count is discernible in STR1, while the separation in STR2 is less pronounced. In STR1, the amplitude of the lower component is slightly larger than the upper component, whereas in STR2, the upper component is larger than the lower component. Significant differences in phase and total density are observed between the two types of stripes. While STR2 tends toward the PW phase, the phase diagram is not as distinct as in PW solitons. The total density in figure

1(b3) for STR1 is also presenting a Gaussian shape, while for STR2 in figure

1(c3), it is elliptical. From these perspectives, STR2 leans more towards the transition state between PW and stripe solitons. To better distinguish these three types of solitons, we represent the relationship between

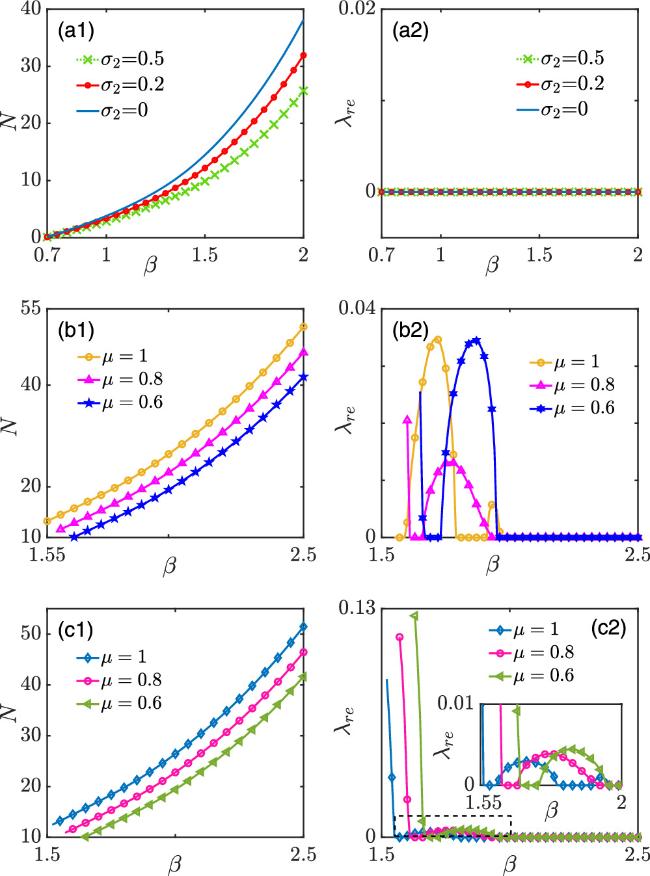

β and the number of particles

N, as well as the relationship between

β and the maximum real of the eigenvalues ${\lambda }_{{re}}$, in figure

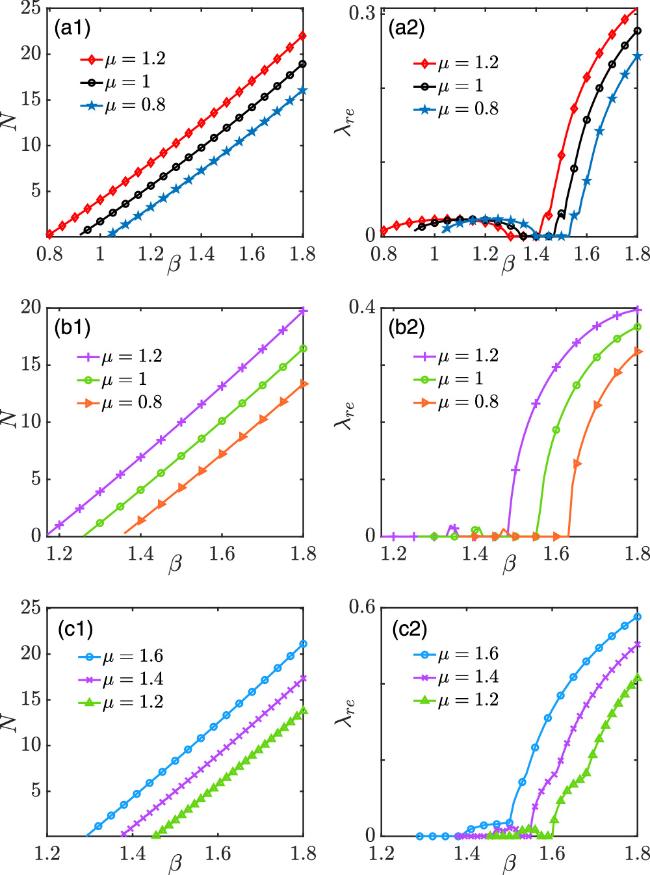

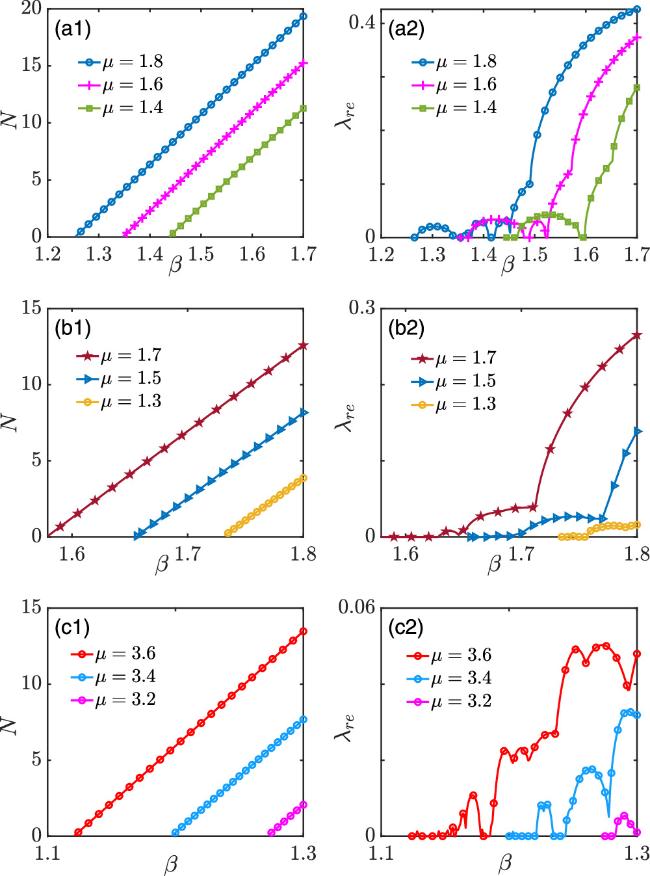

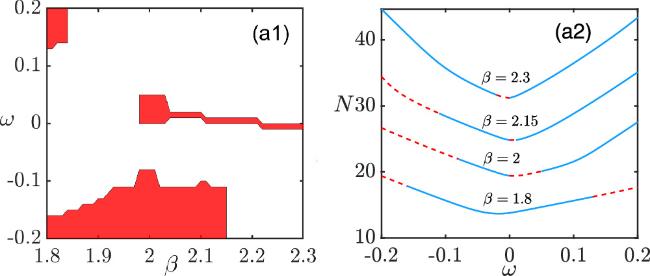

2. From figures

2(a1)–(c1), the

N of PW solitons increases with the increase of

β in different

σ2. The

N of STR1 and STR2 solitons increases with the increase of

β. Analyzing figures

2(a2)–(c2), we observe that all PW solitons in the system are stable. In contrast, stripe solitons exhibit instability at small

β values, gradually stabilizing with increasing

β, with STR2 demonstrating superior stability compared to STR1. Examining figures

2(b2) and (c2), we note that STR1 displays good stability at

μ = 0.8, while the stability of STR2 does not vary significantly at different

μ. This suggests that the stability of STR1 is influenced by both

μ and

β, whereas the stability of STR2 is predominantly affected by

β. Figure

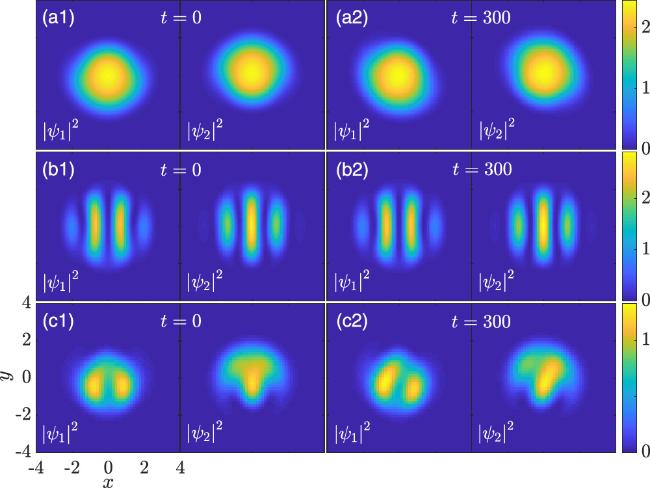

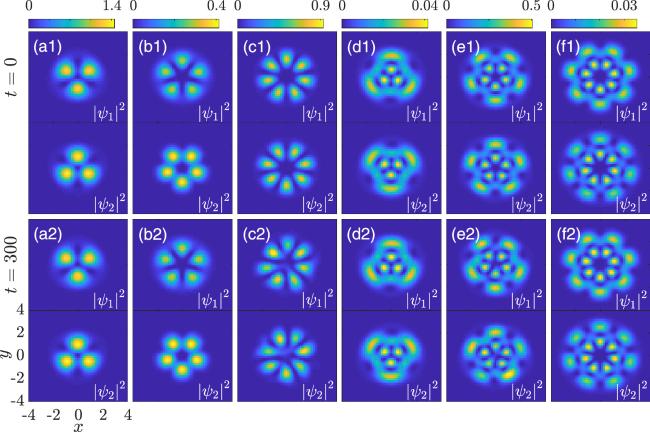

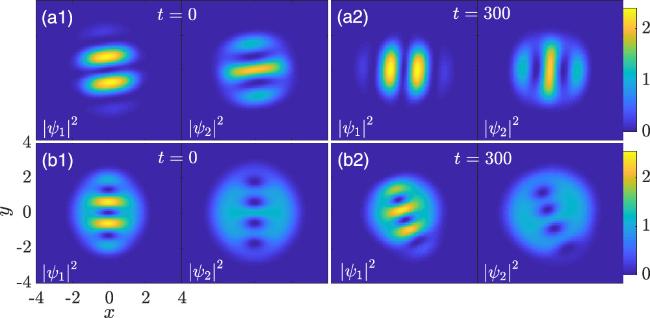

3 presents typical examples illustrating the evolution of both stable and unstable solitons, validating the aforementioned stability analyses. The illustrations in the left column, as shown in figures

3(a1)–(c1), represent the density of spin components

ψ1,2 at

t = 0, while the corresponding right ones, figures

3(a2)–(c2), depict the density after

t = 300. These density maps further affirm the stability of the PW solitons and the stripe solitons. We make both the linear stability analysis and the direct numerical evolution simulations on all discussed solitons, and these results are consistent.