1. Introduction

2. Brief description of the model

| a | (a) Central potential depth parameters: V0 = 49.6 MeV, κ = 0.86. |

| b | (b) Radius parameters of the central part: r0(p) = 1.275 fm, r0(n) = 1.347 fm. |

| c | (c) Radius parameters of the spin-orbit part: r0−so(p) = 1.320 fm, r0−so(n) = 1.310 fm. |

| d | (d) Strength of the spin-orbit potential: λ(p) = 36.0, λ(n) = 35.0. |

| e | (e) Diffuseness parameters of the central part and spin-orbit part: a(p) = a(n) = aso(p) = aso(n) = 0.70 fm. |

3. Results and discussions

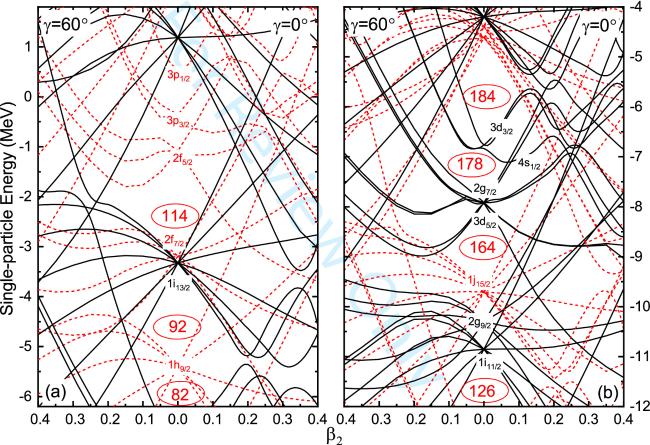

Figure 1. The calculated Woods–Saxon single-particle energy near the Fermi surface in the superheavy nucleus 294Og176. The solid (black) and dotted (red) lines denote the positive and negative parity levels for protons (a) and neutrons (b), respectively. |

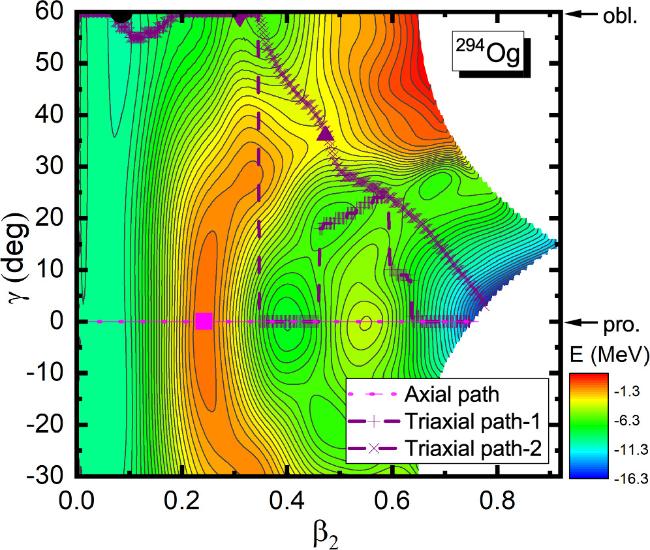

Figure 2. Calculated two-dimensional PES of 294Og in (β2, γ) space minimized over β4. The energy difference between the adjacent contours is 200 keV. The magenta dotted line with minus signs represents the axial fission path (axial path), the purple dashed line with plus signs denotes the triaxial fission path mathematically (triaxial path-1), and the purple dashed line with multiple signs stands for the triaxial fission path physically (triaxial path-2). The black solid circle denotes the ground-state point. The magenta solid square, purple solid lower and upper triangle represent the axial saddle point, triaxial saddle-1 and triaxial saddle-2. Further details are given within the text. |

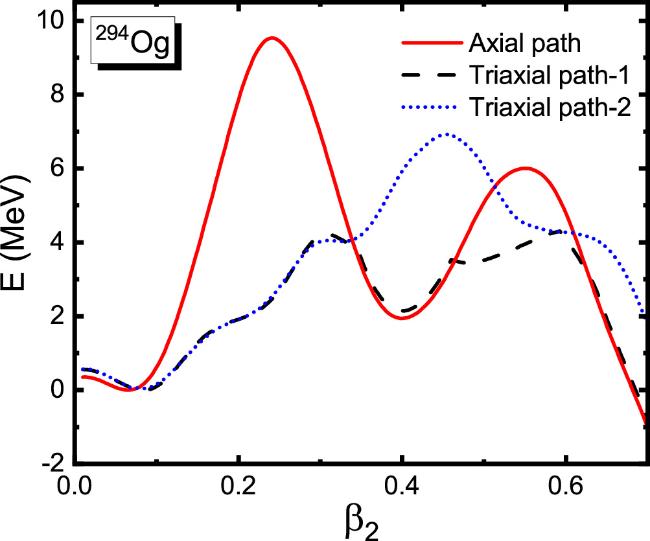

Figure 3. The calculated potential energy curves versus the primary deformation β2 for ${}_{118}^{294}$Og. The red solid line displays the potential energy curve for the axial path, whereas the black dash line shows the corresponding curve along the mathematically triaxial path-1 and the blue dot line represents the physically triaxial path-2. For the convenience of description, the energy curves are normalized with respect to the ground-state energy. |

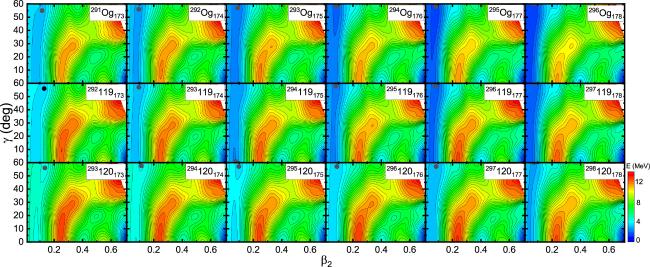

Figure 4. Similar to figure 2, but for 291−296Og, 292−297119, and 293−298120, respectively. For convenience, the energy is normalized with respect to the minimum of each PES. |

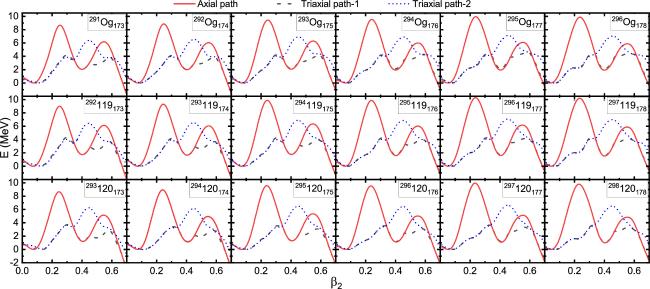

Figure 5. Similar to figure 3, but for 291−296Og, 292−297119, and 293−298120, respectively. |

Table 1. The calculated ground-state deformations β2 and inner fission barrier heights Bf for 291−296Og, 292−297119, and 293−298120. The β2 values with the FY+FRDM (FFD) [75], HN [13], SHFB [76], ETFSI [77] and CDFT [78] calculations, and the inner fission barriers Bf of the FY+FRLDM (FFL) [10], HN [13], SHFB [79], ETFSI [14] and CDFT [80] calculations, are given for comparison. |

| Nuclei | β2 | Bf | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PESa | FFD | HN | ETFSI | SHFB | CDFT | PES | FFL | HN | ETFSI | SHFB | CDFT | |

| Tb | A | A | A | A | T | T | A | T | A | A | T | |

| 291Og | 0.115 | 0.075 | 0.08 | 0.43 | — | — | 6.34 | 8.41 | 6.40 | 7.1 | — | — |

| 292Og | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.08 | 0.43 | −0.12 | 0.012 | 6.64 | 8.41 | 6.09 | 6.8 | 9.11 | 4.35 |

| 293Og | 0.090 | 0.075 | 0.08 | 0.43 | — | — | 6.97 | 8.53 | 6.62 | 7.4 | — | — |

| 294Og | 0.085 | 0.064 | −0.09 | 0.43 | −0.10 | 0.047 | 7.08 | 8.48 | 6.09 | 6.6 | 9.19 | 4.12 |

| 295Og | 0.083 | −0.084 | −0.09 | 0.43 | — | — | 7.38 | 8.46 | 6.64 | 7.1 | — | — |

| 296Og | 0.070 | −0.063 | −0.09 | 0.43 | −0.09 | 0.057 | 7.22 | 8.36 | 6.12 | 7.0 | 9.47 | 3.87 |

| 292119 | 0.130 | 0.086 | 0.08 | 0.43 | — | — | 6.31 | 8.05 | 6.55 | 7.1 | — | — |

| 293119 | 0.095 | 0.075 | 0.08 | 0.43 | — | — | 6.48 | 8.12 | 6.21 | 7.2 | — | — |

| 294119 | 0.078 | 0.075 | 0.08 | 0.43 | — | — | 6.80 | 8.29 | 6.95 | 6.8 | — | — |

| 295119 | 0.080 | 0.075 | 0.08 | 0.43 | — | — | 6.91 | 8.06 | 6.32 | 6.7 | — | — |

| 296119 | 0.080 | 0.064 | −0.10 | 0.43 | — | — | 7.19 | 8.07 | 6.71 | 7.2 | — | — |

| 297119 | 0.073 | −0.063 | −0.09 | 0.43 | — | — | 7.04 | 7.94 | 6.20 | 7.0 | — | — |

| 293120 | 0.135 | 0.086 | 0.09 | 0.43 | — | — | 6.13 | 7.44 | 6.06 | — | — | — |

| 294120 | 0.113 | 0.086 | 0.09 | 0.43 | −0.11 | 0.000 | 6.10 | 7.57 | 5.62 | 5.7 | 9.15 | 4.73 |

| 295120 | 0.098 | 0.075 | 0.09 | 0.43 | — | — | 6.41 | 7.71 | 6.28 | 6.1 | — | — |

| 296120 | 0.088 | 0.075 | 0.09 | 0.43 | −0.10 | 0.000 | 6.47 | 7.69 | 5.79 | 6.2 | 9.48 | 4.92 |

| 297120 | 0.085 | 0.064 | −0.10 | 0.43 | — | — | 6.74 | 7.54 | 6.02 | 6.7 | — | — |

| 298120 | 0.073 | −0.063 | −0.09 | 0.43 | −0.09 | 0.000 | 6.56 | 7.33 | 5.56 | 6.6 | 10.05 | 4.27 |

aThe calculated ∣γ∣ values are not displayed because the ground-state of these nuclei is very soft and near spherical shape. | |

bThe label ‘T' stands for the calculations with triaxial deformation and ‘A' denotes the axial results. |

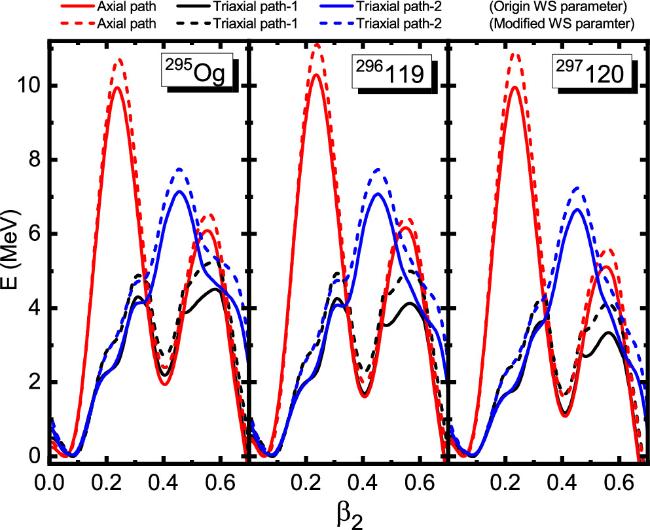

Figure 6. Similar to figure 3, but the potential energy curves compared with the modified Woods–Saxon (WS) parameter combination (ap = 0.73, λp = 38) for the proton-rich N = 177 isotones. All other potential parameters are still equal to those of universal values. |