1. Introduction

2. Theoretical model and procedure

3. Results and discussion

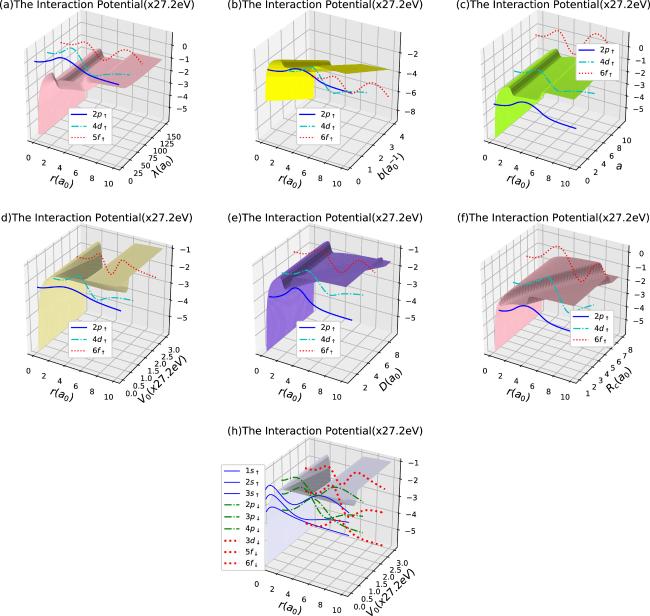

Figure 1. The interaction potential as the plasma plus endofullerene cage confinement and the relevant localized 2p − , 4d − , 6f − wave functions for: (a) b = 1/a0, a = 1, V0 = 20 eV, D = 3.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, Γ = 0.1a0, and R0 = 10a0 as a function of r and λ; (b) λ = 80a0, a = 1, V0 = 20 eV, D = 3.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, Γ = 0.1a0, and R0 = 10a0 as a function of r and b; (c) λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, V0 = 20 eV, D = 3.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, Γ = 0.1a0, and R0 = 10a0 as a function of r and a; (d) λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, a = 1, D = 3.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, Γ = 0.1a0, and R0 = 10a0 as a function of r and V0; (e) λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, a = 1, V0 = 20 eV, Rc = 2.5a0, Γ = 0.1a0, and R0 = 10a0 as a function of r and D; (f) λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, a = 1, V0 = 20 eV, D = 3.5a0, Γ = 0.1a0, and R0 = 10a0 as a function of r and Rc; (g) λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, a = 1, V0 = 20 eV, D = 3.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, and R0 = 10a0 as a function of r and Γ; (h) λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, a = 1, D = 3.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, and R0 = 10a0 as a function of r and V0, with some of the relevant s−, p−, d−, and f− wave functions with spin down. |

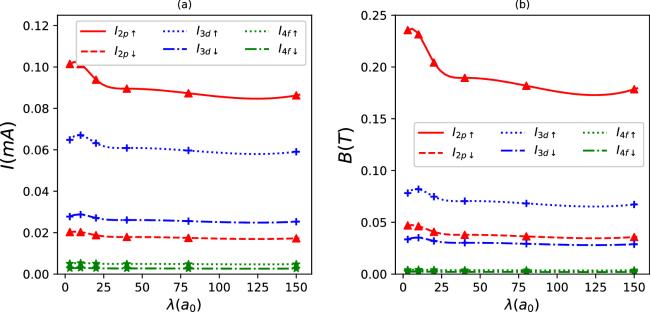

Figure 2. Persistent currents (a) and induced magnetic fields (b) as a function of λ for some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(a). |

Figure 3. The radial density probabilities of 2p (a), 3d (b) and 4f states (c) with spin up for different λ values in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 2, as a function of r. The colored regions are the endohedral cage locations. |

Table 1. Energy values for the λ-change variations of some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(a). |

| λ(a0) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (eV) | 3 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 50 | 100 |

| −E1s | 23.369 184 | 38.704 208 | 43.723 837 | 45.616 53 | 47.205 723 | 48.437 189 |

| −E2p↑ | 16.129 887 | 34.313 389 | 40.400 069 | 42.591 642 | 44.394 841 | 45.771 928 |

| −E2p↓ | 16.131 188 | 34.314 721 | 40.401 542 | 42.593 187 | 44.396 454 | 45.773 599 |

| −E3d↑ | 11.740 014 | 29.964 451 | 36.399 876 | 38.722 676 | 40.633 287 | 42.091 242 |

| −E3d↓ | 11.741 007 | 29.965 421 | 36.400 953 | 38.723 804 | 40.634 461 | 42.092 453 |

| −E4f↑ | 6.663 161 | 24.726 202 | 31.475 002 | 33.922 509 | 35.937 320 | 37.474 900 |

| −E4f↓ | 6.664 184 | 24.727 182 | 31.476 073 | 33.923 620 | 35.938 475 | 37.476 074 |

| −E5g↑ | 18.855 542 | 25.889 311 | 28.455 147 | 30.570 619 | 32.186 171 | |

| −E5g↓ | 18.856 632 | 25.890 469 | 28.456 333 | 30.571 829 | 32.187 398 | |

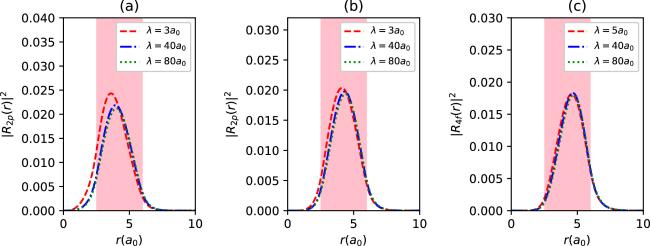

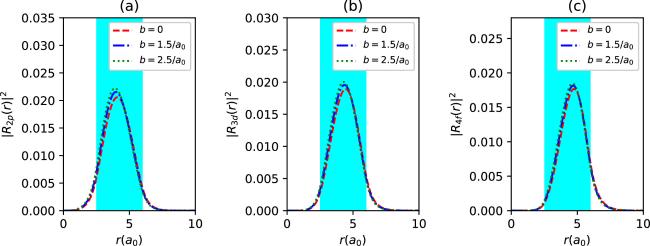

Figure 4. Persistent currents (a) and induced magnetic fields (b) as a function of b for some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(b). |

Figure 5. The radial density probabilities of 2p (a), 3d (b) and 4f states (c) with spin up for different b values in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 4, as a function of r. The colored regions are the endohedral cage locations. |

Table 2. Energy values for the b-change of some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(b). |

| $b({a}_{0}^{-1})$ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (eV) | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.5 |

| −E1s | 22.135 896 | 35.126 214 | 48.126 379 | 61.136 746 | 74.157 680 | 87.189 554 |

| −E2p↑ | 19.603 685 | 32.512 469 | 45.425 905 | 58.343 962 | 71.266 607 | 84.193 810 |

| −E2p↓ | 19.605 418 | 32.514 162 | 45.427 561 | 58.345 581 | 71.268 193 | 84.195 362 |

| −E3d↑ | 16.003 262 | 28.862 127 | 41.725 028 | 54.591 926 | 67.462 782 | 80.337 562 |

| −E3d↓ | 16.004 513 | 28.863 354 | 41.726 230 | 54.593 104 | 67.463 937 | 80.338 695 |

| −E4f↑ | 11.466 867 | 24.275 925 | 37.088 719 | 49.905 199 | 62.725 317 | 75.549 028 |

| −E4f↓ | 11.468 070 | 24.277 109 | 37.089 886 | 49.906 348 | 62.726 448 | 75.550 143 |

| −E5g↑ | 6.257 403 | 19.016 984 | 31.780 344 | 44.547 389 | 57.318 036 | 70.092 208 |

| −E5g↓ | 6.258 648 | 19.018 218 | 31.781 567 | 44.548 601 | 57.319 236 | 70.093 397 |

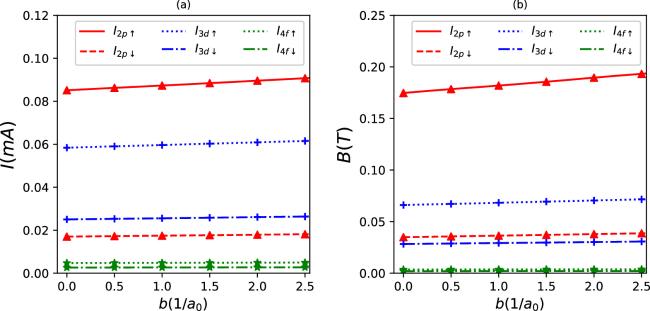

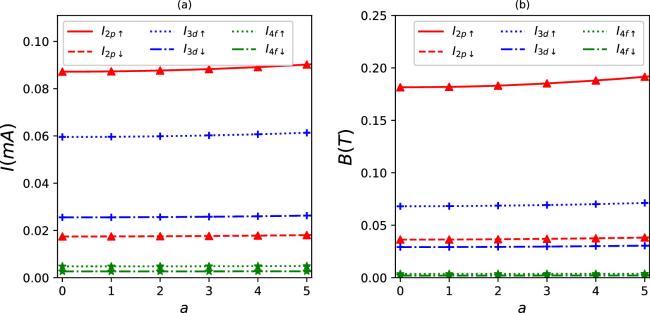

Figure 6. Persistent currents (a) and induced magnetic fields (b) as a function of a for some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(c). |

Figure 7. The radial density probabilities of 2p (a), 3d (b) and 4f states (c) with spin up for different a values in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 6, as a function of r. The colored regions are the endohedral cage locations. |

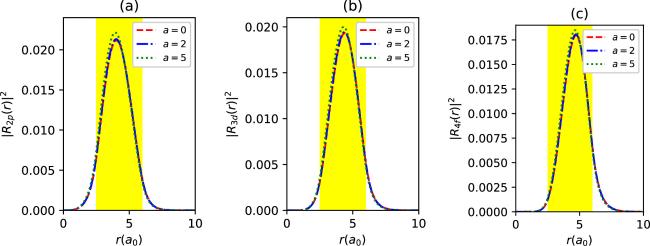

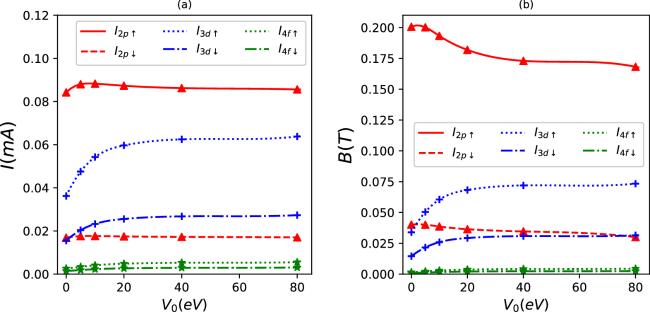

Figure 8. Persistent currents (a) and induced magnetic fields (b) as a function of V0 for some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(d). |

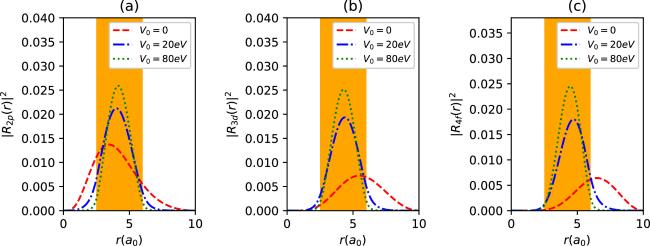

Figure 9. The radial density probabilities of 2p (a), 3d (b) and 4f states (c) with spin up for different V0 values in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 8, as a function of r. The colored regions are the endohedral cage locations. |

Table 3. Energy values for the a-change of some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(c). |

| a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (eV) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| −E1s | 48.162 304 9 | 48.126 379 | 48.019 211 | 47.842 604 | 47.599 517 | 47.293 989 |

| −E2p↑ | 45.469 877 | 45.425 905 | 45.294 458 | 45.076 916 | 44.775 521 | 44.393 286 |

| −E2p↓ | 45.471 536 | 45.427 561 | 45.296 102 | 45.078 542 | 44.777 123 | 44.394 858 |

| −E3d↑ | 41.774 405 | 41.725 028 | 41.577 395 | 41.332 970 | 40.994 129 | 40.564 061 |

| −E3d↓ | 41.775 609 | 41.726 230 | 41.578 589 | 41.334 152 | 40.995 293 | 40.565 205 |

| −E4f↑ | 37.143 814 | 37.088 719 | 36.923 983 | 36.651 231 | 36.273 084 | 35.793 054 |

| −E4f↓ | 37.144 983 | 37.089 886 | 36.925 144 | 36.652 382 | 36.274 222 | 35.794 176 |

| −E5g↑ | 31.841 425 | 31.780 344 | 31.597 747 | 31.295 528 | 30.876 724 | 30.345 358 |

| −E5g↓ | 31.842 649 | 31.781 567 | 31.598 966 | 31.296 741 | 30.877 929 | 30.346 552 |

Table 4. Energy values for the V0-change of some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(d). |

| V0(eV) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (eV) | 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| −E1s | 39.988 977 | 40.738 897 | 42.077 558 | 48.126 379 | 56.787 282 | 66.069 451 |

| −E2p↑ | 28.700 219 | 32.469 805 | 36.592 022 | 45.425 905 | 54.672 085 | 64.130 105 |

| −E2p↓ | 28.700 297 | 32.469 996 | 36.592 550 | 45.427 561 | 54.675 328 | 64.135 591 |

| −E3d↑ | 25.137 047 | 28.615 772 | 32.748 726 | 41.725 028 | 51.077 797 | 60.604 703 |

| −E3d↓ | 25.137 069 | 28.615 940 | 32.749 172 | 41.726 230 | 51.079 928 | 60.607 893 |

| −E4f↑ | 22.291 786 | 24.868 145 | 28.480 711 | 37.088 719 | 46.336 573 | 55.825 394 |

| −E4f↓ | 22.291 799 | 24.868 300 | 28.481 158 | 37.089 886 | 46.338 548 | 55.828 241 |

| −E5g↑ | 19.415 901 | 21.146 414 | 23.954 580 | 31.780 344 | 40.733 353 | 50.075 335 |

| −E5g↓ | 19.415 911 | 21.146 541 | 23.955 015 | 31.781 567 | 40.735 403 | 50.078 240 |

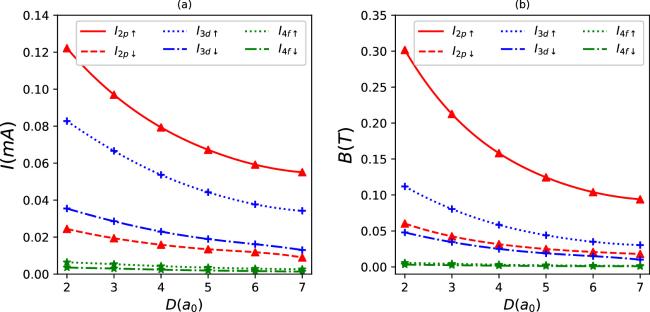

Figure 10. Persistent currents (a) and induced magnetic fields (b) as a function of D for some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(e). |

Figure 11. The radial density probabilities of 2p (a), 3d (b) and 4f states (c) with spin up for different D values in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 10, as a function of r. The colored regions are the endohedral cage locations. |

Table 5. Energy values for the D-change of some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(e). |

| D(a0) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (eV) | 2.5 | 3 | 3.5 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| −E1s | 46.921 265 | 47.627 100 | 48.126 379 | 48.474 227 | 48.877 592 | 49.059 312 |

| −E2p↑ | 43.371 295 | 44.577 101 | 45.425 905 | 46.027 627 | 46.763 044 | 47.132 761 |

| −E2p↓ | 43.373 663 | 44.579 078 | 45.427 561 | 46.029 019 | 46.764 042 | 47.133 480 |

| −E3d↑ | 38.786 692 | 40.478 537 | 41.725 028 | 42.653 036 | 43.878 439 | 44.574 271 |

| −E3d↓ | 38.788 304 | 40.479 927 | 41.726 230 | 42.654 078 | 43.879 225 | 44.574 829 |

| −E4f↑ | 32.999 393 | 35.305 532 | 37.088 719 | 38.475 516 | 40.419 585 | 41.617 762 |

| −E4f↓ | 33.000 807 | 35.306 821 | 37.089 886 | 38.476 571 | 40.420 444 | 41.618 414 |

| −E5g↑ | 26.419 586 | 29.370 098 | 31.780 344 | 33.724 784 | 36.562 074 | 38.392 075 |

| −E5g↓ | 26.420 898 | 29.371 389 | 31.781 567 | 33.725 928 | 36.563 055 | 38.392 846 |

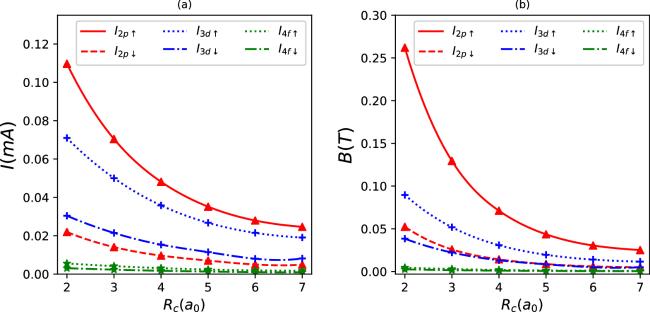

Figure 12. Persistent currents (a) and induced magnetic fields (b) as a function of Rc for some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(f). |

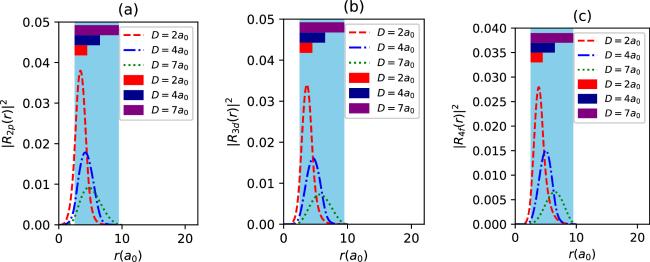

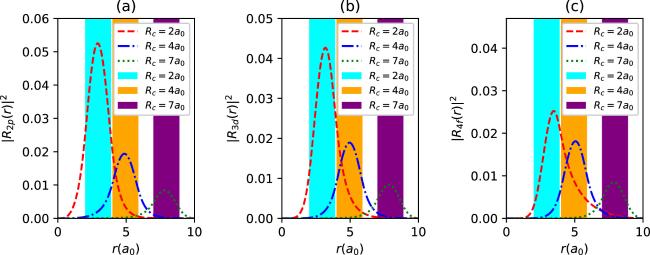

Figure 13. The radial density probabilities of 2p (a), 3d (b) and 4f states (c) with spin up for different Rc values in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 12, as a function of r. The colored regions are the endohedral cage locations. |

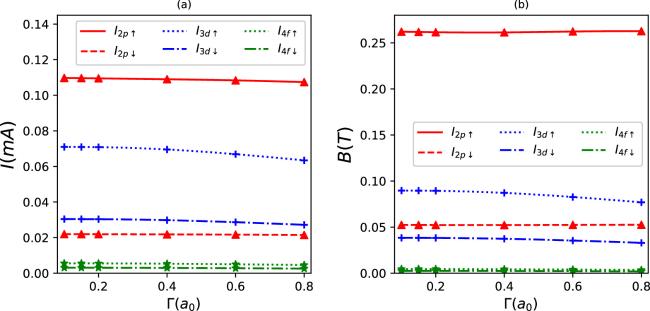

Figure 14. Persistent currents (a) and induced magnetic fields (b) as a function of Γ for some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1g. |

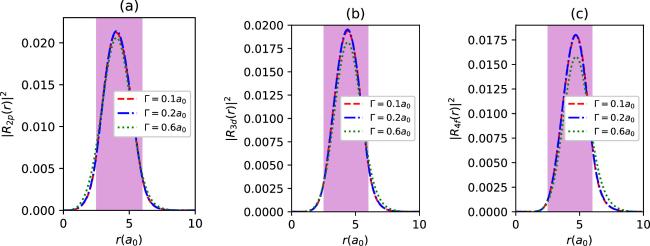

Figure 15. The radial density probabilities of 2p (a), 3d (b) and 4f states (c) with spin up for different Γ values in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 14, as a function of r. The colored regions are the endohedral cage locations. |

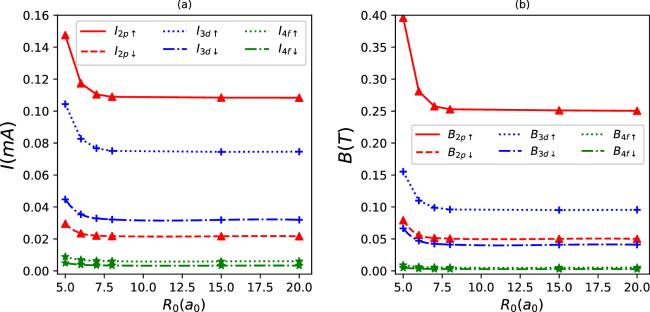

Figure 16. Persistent currents (a) and induced magnetic fields (b) as a function of R0 for some quantum states, when λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, a = 1, V0 = 20 eV, D = 2.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, and Γ = 0.1a0. |

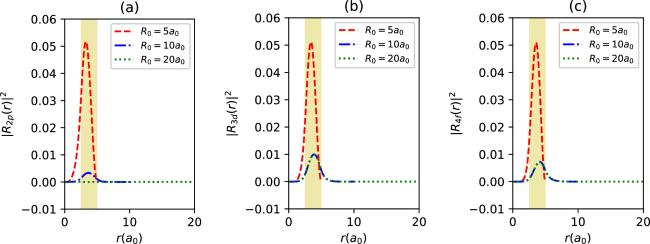

Figure 17. The radial density probabilities of 2p (a), 3d (b) and 4f states (c) with spin up for different Γ values, when λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, a = 1, V0 = 20 eV, D = 2.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, and Γ = 0.1a0, as a function of r. The colored regions are the endohedral cage locations. |

Table 6. Energy values for the Rc-change of some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(f). |

| Rc(a0) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (eV) | 2.5 | 3 | 3.5 | 4 | 4.5 | 5 |

| −E1s | 48.126 379 | 46.838 977 | 45.838 567 | 45.033 708 | 44.355 463 | 43.738 906 |

| −E2p↑ | 45.425 905 | 44.919 674 | 44.420 278 | 43.944 126 | 43.487 505 | 43.024 168 |

| −E2p↓ | 45.427 561 | 44.921 733 | 44.422 819 | 43.947 226 | 43.491 244 | 43.028 630 |

| −E3d↑ | 41.725 028 | 41.996 429 | 42.073 720 | 42.026 291 | 41.891 154 | 41.670 046 |

| −E3d↓ | 41.726 230 | 41.997 772 | 42.075 257 | 42.028 064 | 41.893 186 | 41.672 316 |

| −E4f↑ | 37.088 719 | 38.146 105 | 38.867 048 | 39.335 035 | 39.608 013 | 39.706 681 |

| −E4f↓ | 37.089 886 | 38.147 304 | 38.868 326 | 39.336 431 | 39.609 549 | 39.708 341 |

| −E5g↑ | 31.780 344 | 33.581 400 | 34.955 272 | 35.978 111 | 36.711 330 | 37.183 243 |

| −E5g↓ | 31.781 567 | 33.582 605 | 34.956 491 | 35.979 376 | 36.712 661 | 37.184 626 |

Table 7. Energy values for the Γ-change of some quantum states in synchronization with the parameter set in figure 1(g). |

| Γ(a0) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (eV) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| −E1s | 48.126 379 | 47.881 460 | 47.547 542 | 47.182 011 | 46.841 177 | 46.566 542 |

| −E2p↑ | 45.425 905 | 45.108 175 | 44.630 063 | 44.033 354 | 43.365 404 | 42.670 114 |

| −E2p↓ | 45.427 561 | 45.109 029 | 44.630 672 | 44.033 843 | 43.365 810 | 42.670 450 |

| −E3d↑ | 41.725 028 | 41.406 715 | 40.919 619 | 40.304 372 | 39.610 619 | 38.885 777 |

| −E3d↓ | 41.726 230 | 41.407 357 | 40.920 084 | 40.304 751 | 39.610 940 | 38.886 051 |

| −E4f↑ | 37.088 719 | 36.777 899 | 36.309 170 | 35.724 994 | 35.075 309 | 34.406 898 |

| −E4f↓ | 37.089 886 | 36.778 524 | 36.309 622 | 35.725 361 | 35.075 619 | 34.407 164 |

| −E5g↑ | 31.780 344 | 31.478 579 | 31.046 868 | 30.532 894 | 29.983 593 | 29.439 173 |

| −E5g↓ | 31.781 567 | 31.479 231 | 31.047 334 | 30.533 267 | 29.983 905 | 29.439 438 |

Table 8. Energy values for the R0-change of some quantum states when λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, a = 1, V0 = 20 eV, D = 3.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, and Γ = 0.1a0. |

| R0(a0) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (eV) | 3 | 5 | 9 | 11 | 15 | 20 |

| −E1s | 38.324 953 | 45.126 285 | 48.125 575 | 48.126 444 | 48.126 450 | 48.126 450 |

| −E2p↑ | 14.405 374 | 39.832 223 | 45.423 953 | 45.426 087 | 45.426 105 | 45.426 105 |

| −E2p↓ | 14.406 259 | 39.833 028 | 45.425 606 | 45.427 743 | 45.427 761 | 45.427 761 |

| −E3d↑ | − | 33.705 014 | 41.720 405 | 41.725 555 | 41.725 620 | 41.725 620 |

| −E3d↓ | − | 33.705 372 | 41.721 605 | 41.726 757 | 41.726 823 | 41.726 823 |

| −E4f↑ | − | 25.768 276 | 37.076 815 | 37.090 487 | 37.090 787 | 37.090 787 |

| −E4f↓ | − | 25.768 464 | 37.077 979 | 37.091 654 | 37.091 954 | 37.091 954 |

| −E5g↑ | − | 16.168 733 | 31.748 698 | 31.786 902 | 31.788 620 | 31.788 623 |

| −E5g↓ | − | 16.168 836 | 31.749 918 | 31.788 125 | 31.789 842 | 31.789 845 |

Table 9. The magnetic quantum number (m) effect on the PC and IMF, when λ = 80a0, b = 1/a0, a = 1, V0 = 20 eV, D = 3.5a0, Rc = 2.5a0, Γ = 0.1a0, and R0 = 10a0. |

| ∣nℓmℓms⟩ | I(mA) | B(T) |

|---|---|---|

| ∣111 + 1/2⟩ | 0.087 317 | 0.181 876 |

| ∣111 − 1/2⟩ | 0.017 464 | 0.036 404 |

| ∣122 + 1/2⟩ | 0.019 171 | 0.043 876 |

| ∣122 − 1/2⟩ | 0.002 130 | 0.004 875 |

| ∣121 + 1/2⟩ | 0.059 643 | 0.068 252 |

| ∣121 − 1/2⟩ | 0.025 561 | 0.029 254 |

| ∣133 + 1/2⟩ | 0.000 115 | 0.000 263 |

| ∣133 − 1/2⟩ | 0.000 008 | 0.000 020 |

| ∣132 + 1/2⟩ | 0.005 802 | 0.008 795 |

| ∣132 − 1/2⟩ | 0.001 582 | 0.002 398 |

| ∣131 + 1/2⟩ | 0.004 809 | 0.003 645 |

| ∣131 − 1/2⟩ | 0.002 671 | 0.002 024 |