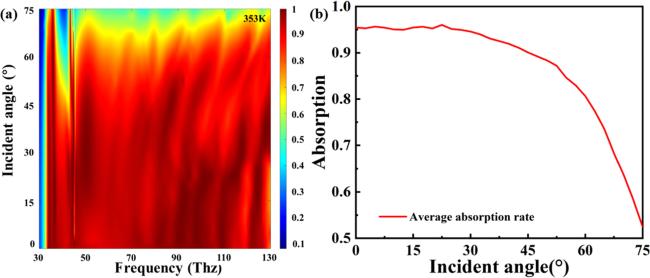

Figure

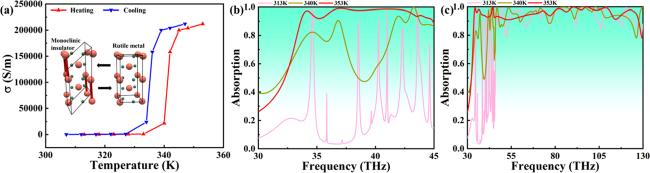

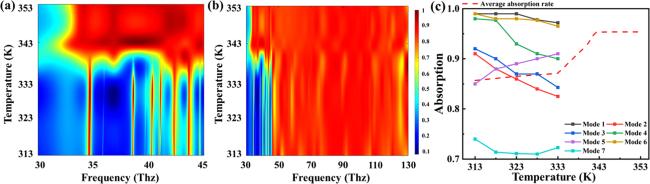

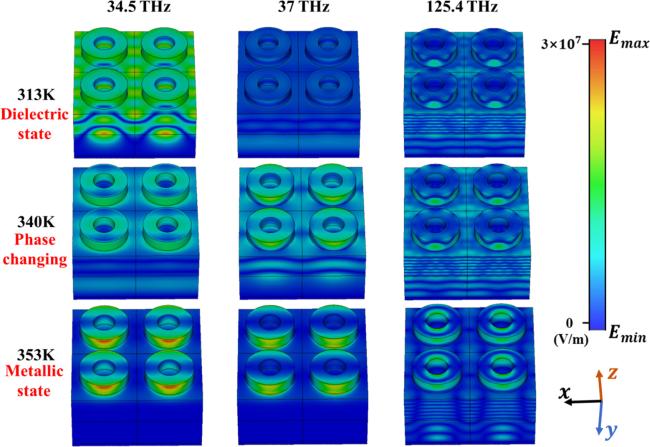

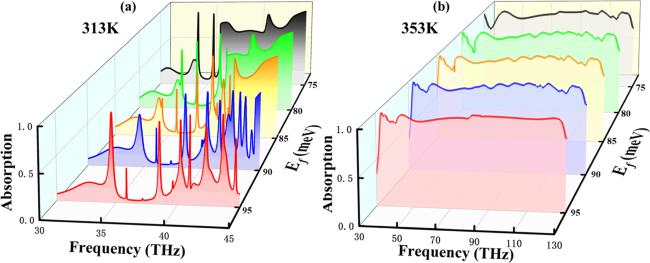

5 shows the scanning spectrum of the absorption film at 313–353 K (figure

5(a) in the 30–45 THz band and figure

5(b) in the 30–130 THz band). We can see from figure

3(a) that when the temperature reaches around 340 K, the atomic lattice of VO

2 will change from monoclinic insulator to rutile metal, and the macroscopic properties of VO

2 will gradually transform from a dielectric state to a metallic state. It is evident that in the 30–45 THz band, when the temperature gradually increases from 313 K to 335 K, the absorption film still exhibits a seven-band absorption optical response. Subsequently, as the temperature reaches 340 K, VO

2 gradually transforms into a metallic state, and the optical response gradually transforms into bandwidth absorption, reaching a stable state when phase transition is completed (at about 343 K). Figure

5(b) shows that when the temperature is lower than the phase transition temperature, the bandwidth of the absorption wave of the absorption film shows multiple defects with an absorption rate lower than 0.8. As the temperature increases, the absorption band of the absorber film gradually stabilizes. Finally, at a temperature of 353 K, the absorption rates of the absorption band are all greater than 0.9. Figure

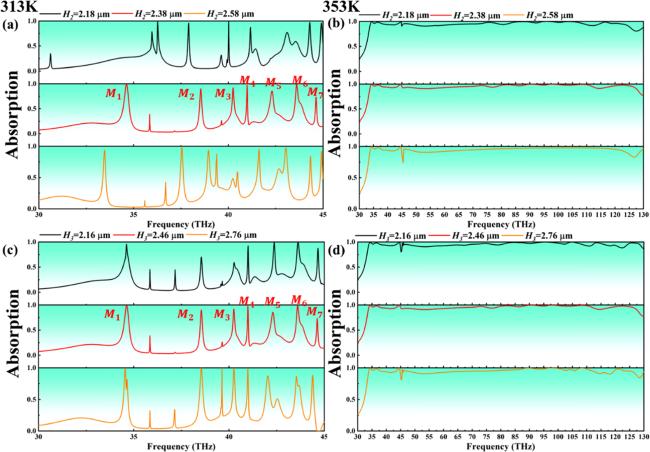

5(c) depicts the absorption rate of each mode as well as the average absorption rate within the 35–130 THz band. Notably, modes 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 exhibit a decrease in absorption rate with increasing temperature. This phenomenon can be attributed to the increased metallicity of VO

2, resulting in a weakened localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect [

48,

49]. Conversely, mode 5 displays an increase in absorption rate as the temperature rises. This suggests that as VO

2 transitions into a metallic state, the enhancement of guided-mode resonance coupling and electromagnetic coupling leads to higher energy absorption in mode 5. Additionally, mode 7 initially weakens and subsequently strengthens with increasing temperature. This behavior is due to the fact that, at a certain temperature, the gain introduced by guided-mode resonance coupling surpasses the loss caused by the weakening of the LSPR effect [

50]. Overall, as the temperature rises, the metallic state of VO

2 amplifies the effects of guided-mode resonance and electromagnetic coupling, thereby enhancing the overall electromagnetic absorption capacity [

51]. This gain can be more distinctly observed around the phase transition point (approximately 340 K).