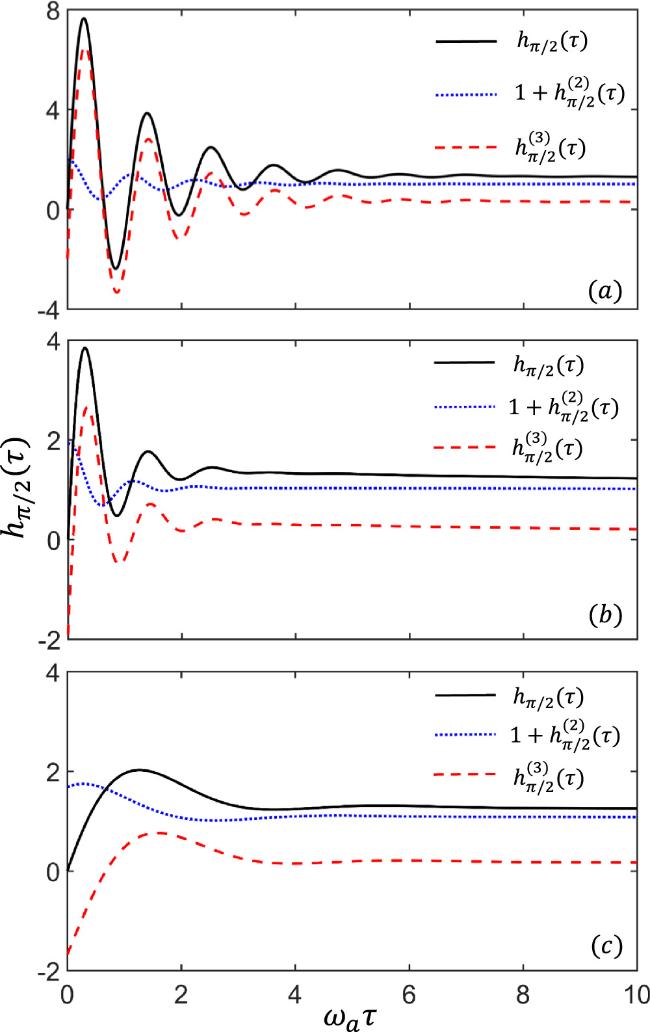

For the case of avoided-crossing with

g/

ωq = 0.2, the analytical results of the intensity-amplitude correlation in the USC regime are shown in figure

3, which align well with the numerical results in figure

1. The dominant oscillation frequency is Ω, as illustrated by the dashed red curve in figure

3, which originates from the transition channels ∣+⟩ → ∣−⟩ and ∣−⟩ → ∣+⟩. It also represents the Rabi oscillations between ∣

$Psi$0⟩ and ∣

$Psi$3⟩. Evidently, the damping becomes faster as the decay rate (2

A + Γ

30)/4 increases, and the frequencies of

hπ/2(

τ) decrease with the decreasing driving strength

ϵ. Furthermore,

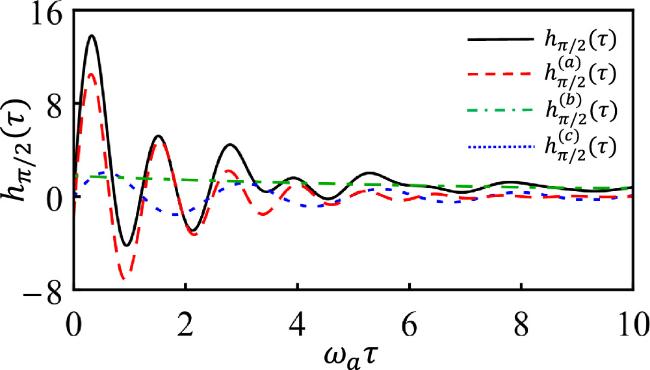

${h}_{\pi /2}^{(b)}(\tau )$ (dash-dotted green curve) illustrates the evolutions caused by the narrow peaks at the center of the spectrum. Due to the zero frequencies of

${\lambda }_{1}^{\pm }$, there is no oscillation. Furthermore, compared with the decay rate (2

A + Γ

30)/4, the decay processes with rates (

D ± Δ)/4 are much slower, leading

${h}_{\pi /2}^{(b)}(\tau )$ to barely evolve over time. However, as

κ increases in figure

3(b), it can still be seen that the decay processes will be slightly faster. Because

α03 ≪

α13, the evolution from

${h}_{\pi /2}^{(c)}(\tau )$ (dotted blue curve) is barely noticeable in the intensity-amplitude correlation.