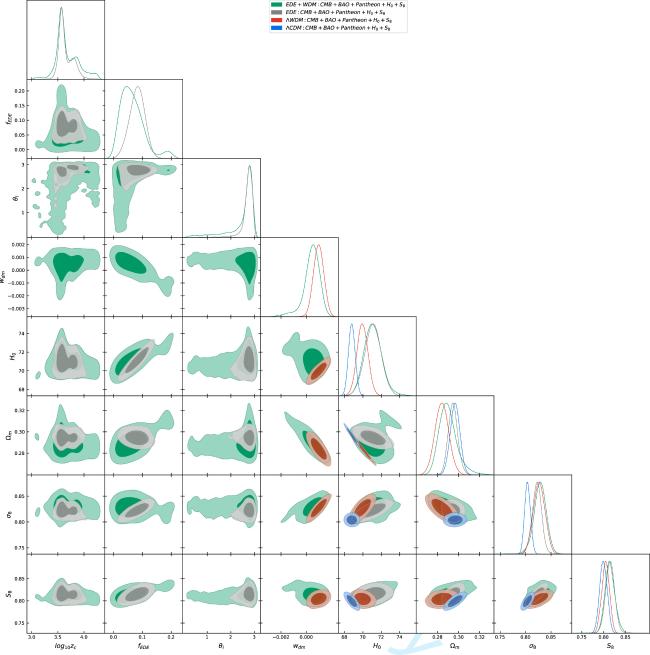

In table

1, we present the observational constraints on EDE+WDM, EDE, ΛWDM and ΛCDM based on the CMB+BAO+Pantheon+

H0+

S8 dataset. Figure

2 shows the one-dimensional posterior distributions and two-dimensional joint contours at 68% and 95% confidence levels for the most relevant parameters of EDE+WDM, EDE, ΛWDM and ΛCDM. From table

1, one can see that the values of parameters

wdm of both EDE+WDM and ΛWDM are very close to 0. This does not come as a surprise, since otherwise the LSS cannot be correctly formed. In addition, we find that the fitting results for the

H0 parameter in EDE+WDM, i.e.

${71.11}_{-1.0}^{+0.88}$ at 68% confidence level, are similar to that of EDE, i.e. 71.10 ± 0.90 at 68% confidence level. It still maintains the ability to alleviate the Hubble tension to ∼1.4

σ, which is a notable improvement compared to that of ΛWDM, i.e. 69.95 ± 0.60 at 68% confidence level (with Hubble tension ∼2.6

σ) and that of ΛCDM, i.e. 68.79 ± 0.37 at 68% confidence level (with Hubble tension ∼3.9

σ). However, unfortunately, we find that the fitting result for the

S8 parameter in EDE+WDM, i.e.

${0.814}_{-0.012}^{+0.011}$ at 68% confidence level, is also similar to that of EDE, i.e. 0.815 ± 0.011 at 68% confidence level, showing a ∼2.3

σ tension on the

S8 parameter, which is still worse than that of ΛWDM, i.e.

${S}_{8}={0.8043}_{-0.0084}^{+0.0093}$ 68% confidence level (with

S8 tension ∼2

σ) and that of ΛCDM, i.e.

S8 = 0.7994 ± 0.0086 68% confidence level (with

S8 tension ∼1.8

σ). We attribute the failure of the EDE+WDM model to alleviate the

S8 tension to the lack of a positive(negative) correlation between the

S8 parameter and the

wdm parameter, as well as a sufficiently large negative(positive) value of

wdm in this model. Although, as expected, there is a positive correlation between the

wdm parameter and the

σ8 parameter in this model, the negative correlation between the

wdm parameter and Ω

m leads to the lack of correlation between the

S8 parameter and the

wdm parameter. This is somewhat different from the situation in ΛWDM. Although in ΛWDM, the

wdm parameter is also positively correlated with the

σ8 parameter while being negatively correlated with the Ω

m parameter, it still results in a slight positive correlation between the

wdm parameter and the

S8 parameter. We note that even though there is a slight positive correlation between the

wdm parameter and the

S8 parameter in the ΛWDM case, such a model still exacerbates the

S8 tension compared to ΛCDM due to the positive value of

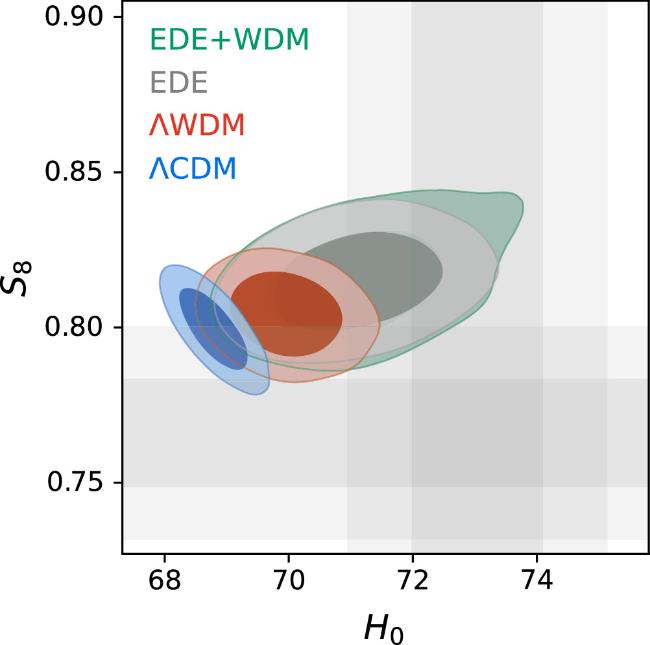

wdm. To visually illustrate the tension among the fitting results of EDE+WDM, EDE, ΛWDM, ΛCDM and the two priors included in the datasets (R22 and the Gaussianized prior on

S8), figure

3 reproduces the

S8-

H0 contours, incorporating the boundaries corresponding to one standard deviation for these two priors. It is worth mentioning that the above result is still obtained when using both

H0 prior and

S8 prior simultaneously. If we were to use only one of these priors, or none at all, the EDE+WDM model would face even greater Hubble and

S8 tensions.