1. Introduction

2. Model introduction

Figure 1. A schematic representation of the particles suspended in isotropic liquid crystal (2D). |

3. Results

3.1. Interaction between colloidal particles in 2D geometry

Table 1. A list of dimensionless physical quantities. Here, ${\bar{G}}^{(2)}$ and ${\bar{F}}^{(2)}$ represent the free energy and the effective force in the 2D case, and ${\bar{G}}^{(3)}$ and ${\bar{F}}^{(3)}$ represent the free energy and the effective force in the 3D case. |

| Dimensionless variables | Expression | Dimensionless variables | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| $\bar{x}$ | x/L0 | $\bar{y}$ | y/L0 |

| $\bar{z}$ | z/L0 | $\bar{r}$ | r/L0 |

| $\bar{H}$ | H/L0 | $\bar{R}$ | R/L0 |

| ${\bar{G}}^{(2)}$ | $G/\alpha {L}_{0}^{2}$ | ${\bar{G}}^{(3)}$ | $G/\alpha {L}_{0}^{3}$ |

| ${\bar{F}}^{(2)}$ | F/αL0 | ${\bar{F}}^{(3)}$ | $F/\alpha {L}_{0}^{2}$ |

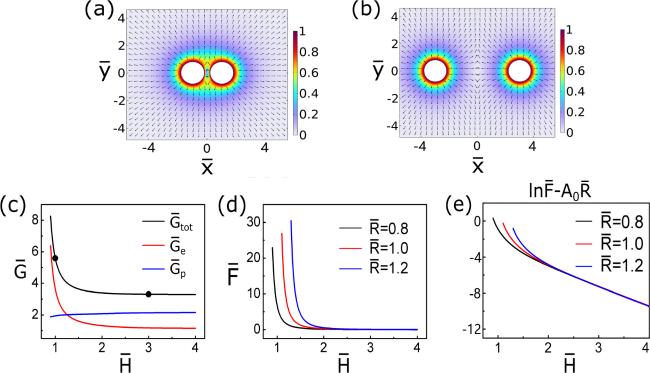

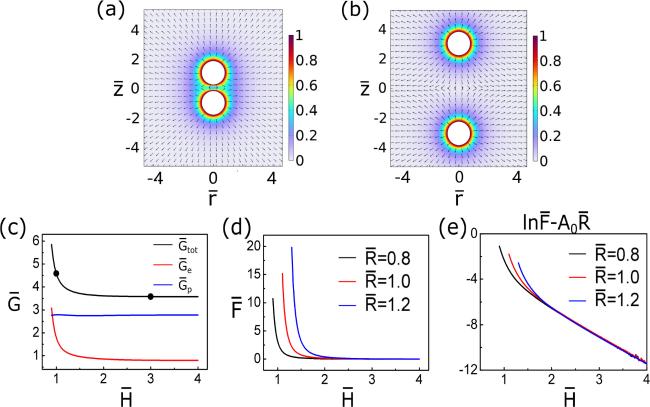

Figure 2. The interaction between two circular particles with symmetric homeotropic anchoring conditions in a 2D plane. (a, b) Distribution of the polar order parameter p around the two particles. The black arrows indicate the orientation of p, and the color codes represent the magnitude of p. The radius of the particles is $\bar{R}=0.8$, and the distance is $\bar{H}=1$ in (a) and $\bar{H}=3$ in (b). (c) The total free energy ${\bar{G}}_{\mathrm{tot}}$ (black line), elastic energy ${\bar{G}}_{{\rm{e}}}$ (red line), and polarization energy ${\bar{G}}_{{\rm{p}}}$ (blue line) are treated as functions of the distance $\bar{H}$ between the two particles. The dots in (c) indicate the corresponding points calculated in (a) and (b). (d) The relationship between the effective force $\bar{F}$ and the distance $\bar{H}$. The radii of particles are 0.8 (black line), 1.0 (red line), and 1.2 (blue line), respectively. (e) The relationship between $\mathrm{ln}(\bar{F})-{A}_{0}\bar{R}$ and $\bar{H}$. Here, A0 = 3.5. The radii of particles are 0.8 (black line), 1.0 (red line), and 1.2 (blue line), respectively. |

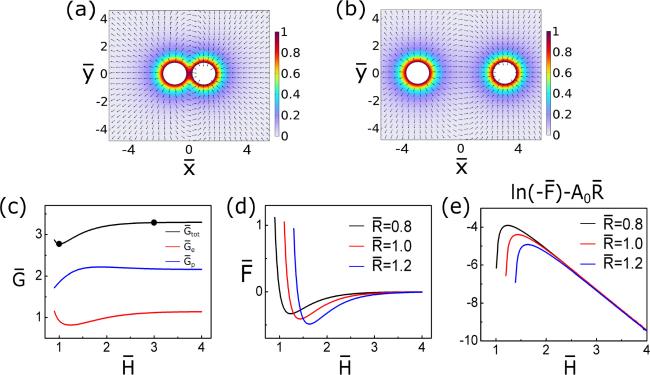

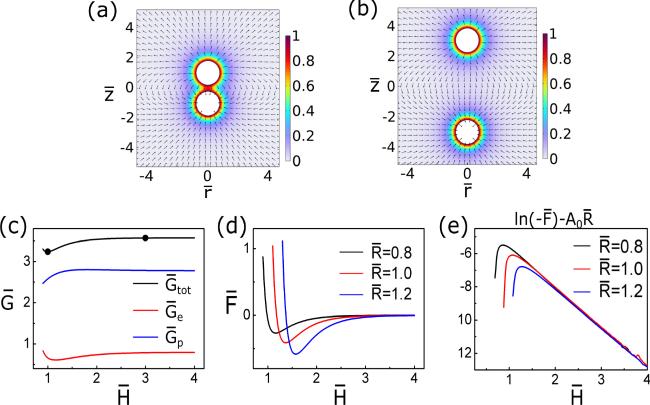

Figure 3. The interaction between two circular particles with anti-symmetric homeotropic anchoring conditions in a 2D plane. (a, b) Distribution of the polar order parameter p around the two particles. The black arrows indicate the orientation of p, and the color codes represent the magnitude of p. The radius of the particles is $\bar{R}=0.8$, and the distance is $\bar{H}=1$ in (a) and $\bar{H}=3$ in (b). (c) The total free energy ${\bar{G}}_{\mathrm{tot}}$ (black line), elastic energy ${\bar{G}}_{{\rm{e}}}$ (red line), and polarization energy ${\bar{G}}_{{\rm{p}}}$ (blue line) are treated as functions of the distance $\bar{H}$ between the two particles. The dots in (c) indicate the corresponding points calculated in (a) and (b). (d) The relationship between the effective force $\bar{F}$ and the distance $\bar{H}$. The radii of particles are 0.8 (black line), 1.0 (red line), and 1.2 (blue line), respectively. (e) The relationship between $\mathrm{ln}(-\bar{F})-{A}_{0}\bar{R}$ and $\bar{H}$. Only the parts below the x-axis are drawn. Here, A0 = 3.5. The radii of particles are 0.8 (black line), 1.0 (red line), and 1.2 (blue line), respectively. |

3.2. Interaction between colloidal particles in 3D geometry

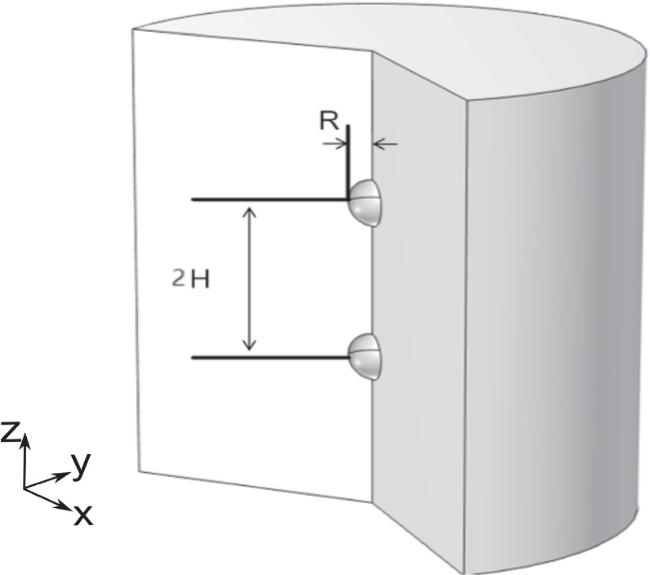

Figure 4. A schematic representation of the particles suspended in isotropic LC (3D). |

Figure 5. The interaction between two particles with symmetric homeotropic anchoring conditions in 3D LCs. (a, b) Distribution of the polar order parameter p around the two particles on a cross-section of the r-z plane. The black arrows represent the orientation of p, and the color codes represent the magnitude of p. The particle radius $\bar{R}=0.8$, and the distance $\bar{H}=1$ in (a) and $\bar{H}=3$ in (b). (c) The total free energy ${\bar{G}}_{\mathrm{tot}}$ (black line), elastic energy ${\bar{G}}_{{\rm{e}}}$ (red line), and polarization energy ${\bar{G}}_{{\rm{p}}}$ (blue line) are treated as functions of the distance $\bar{H}$ between the two particles. The dots in (c) indicate the corresponding points calculated in (a) and (b). (d) The relationship between the effective force $\bar{F}$ and the distance $\bar{H}$. The radii of particles are 0.8 (black line), 1.0 (red line), and 1.2 (blue line), respectively. (e) The relationship between $\mathrm{ln}(\bar{F})-{A}_{0}\bar{R}$ and $\bar{H}$. Here, A0 = 5.2. The radii of particles are 0.8 (black line), 1.0 (red line), and 1.2 (blue line), respectively. |

Figure 6. The interaction between two particles with anti-symmetric homeotropic anchoring conditions in 3D LCs. (a, b) Distribution of the polar order parameter p around the two particles on a cross-section of the r-z plane. The black arrows represent the orientation of p, and the color codes represent the magnitude of p. The particle radius $\bar{R}=0.8$, and the distance $\bar{H}=1$ in (a) and $\bar{H}=3$ in (b). (c) The total free energy ${\bar{G}}_{\mathrm{tot}}$ (black line), elastic energy ${\bar{G}}_{{\rm{e}}}$ (red line), and polarization energy ${\bar{G}}_{{\rm{p}}}$ (blue line) are treated as functions of the distance $\bar{H}$ between the two particles. The dots in (c) indicate the corresponding points calculated in (a) and (b). (d) The relationship between the effective force $\bar{F}$ and the distance $\bar{H}$. The radii of particles are 0.8 (black line), 1.0 (red line), and 1.2 (blue line), respectively. (e) The relationship between $\mathrm{ln}(-\bar{F})-{A}_{0}\bar{R}$ and $\bar{H}$. Only the parts below the x-axis are drawn. The constant A0 = 5.2. The radii of particles are 0.8 (black line), 1.0 (red line), and 1.2 (blue line), respectively. |

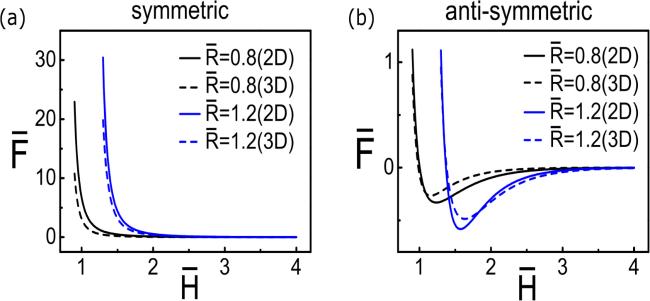

Figure 7. Comparison between 2D and 3D cases. (a, b) The relationship between the effective force $\bar{F}$ and the distance $\bar{H}$ in 2D (solid line) and 3D (dash line) with symmetric homeotropic anchoring conditions in (a) and anti-symmetric homeotropic anchoring conditions in (b). The radii of particles are 0.8 (black line) and 1.2 (blue line), respectively. |

4. Discussion

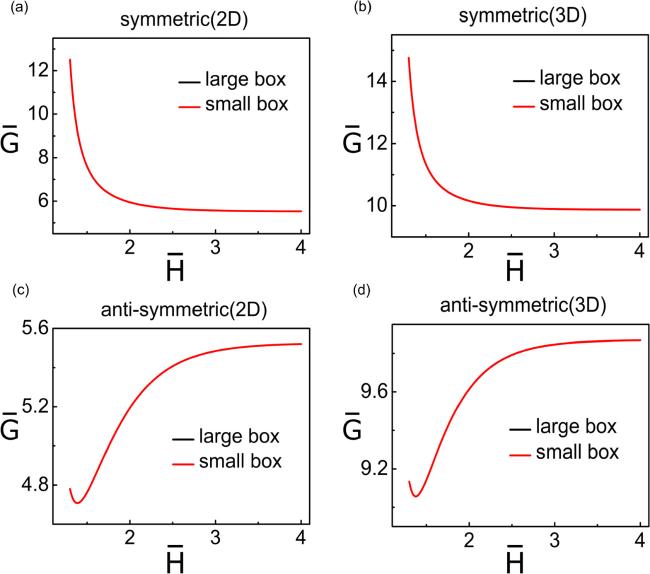

Figure 8. The relationship between the free energy $\bar{G}$ and the distance $\bar{H}$ in a large box and in a small box for a particle size $\bar{R}=1.2$. (a, b) The results with symmetric homeotropic anchoring conditions in 2D (a) and 3D (b). (c, d) The results with anti-symmetric homeotropic anchoring conditions in 2D (c) and 3D (d). For 2D geometry, the small box has a length of 80L0 and a width of 40L0, and the large box has a length of 120L0 and a width of 60L0. For 3D geometry, the small box has a height of 80L0, and a radius of 20L0, and the large box has a length of 120L0 and a radius of 60L0. The small boxes in (a) and (c) are the same as in figures 2 and 3; those in (b) and (d) are the same as in figures 5 and 6. |