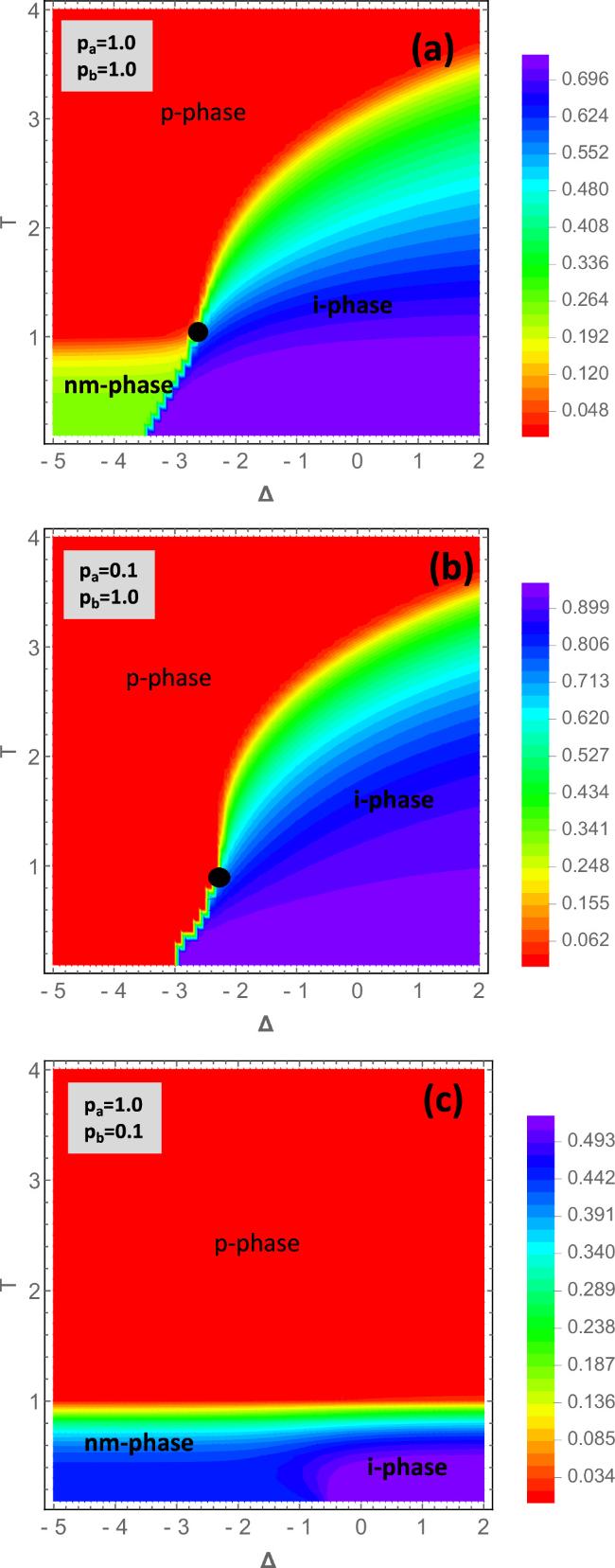

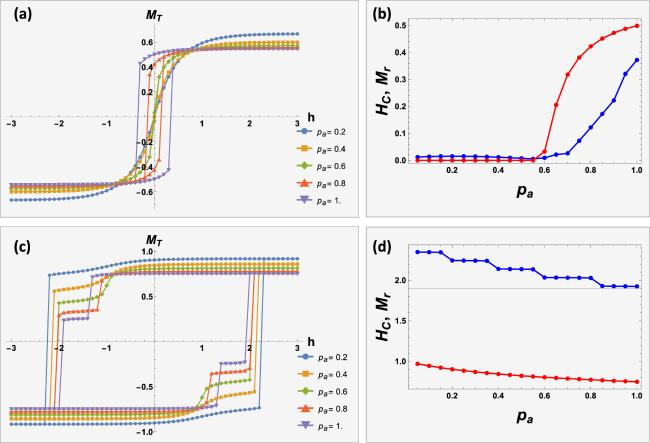

In this subsection, the hysteresis characteristics of the system are examined with regard to their dependence on temperature, segment dilutions, and crystal field and are presented in figures

6–

8. The investigation of hysteresis loops in low-dimensional nanostructures has been conducted through the utilization of MCS [

43,

65–

69]. Kantar [

70] examined the thermal and magnetic properties of a hexagonal Ising nanowire and various other systems [

25,

71] using EFT. When analyzing the hysteresis behavior in the figures, two different states of

pb were taken into account, such as

pb = 0.1 and

pb = 1.0. Initially, the effect of increasing

pa was examined for the

pb = 0.1 case, which revealed a decrease in HLA as

pa increased, as seen in figure

6(a). Upon analyzing the

HC and

Mr values corresponding to these

pa values, it was found that the system was paramagnetic up to a certain value of

pa, beyond which the values of these two parameters began to increase, as seen in figure

6(b). In contrast, the hysteresis behavior observed for the second case, where

pb = 1.0, displayed distinct behavior. As the value of

pa increases, the HLA becomes narrower and the

HC and

Mr tend to decrease, as seen in figures

6(c) and (d). The reason for this difference is that at small values of

pb and

pa, the system is in the paramagnetic region, and then at increasing values of

pa, the system reaches the ferrimagnetic region. In this case, the dominant segment on the magnetic character of the system is the spin-1/2 segment. Figure

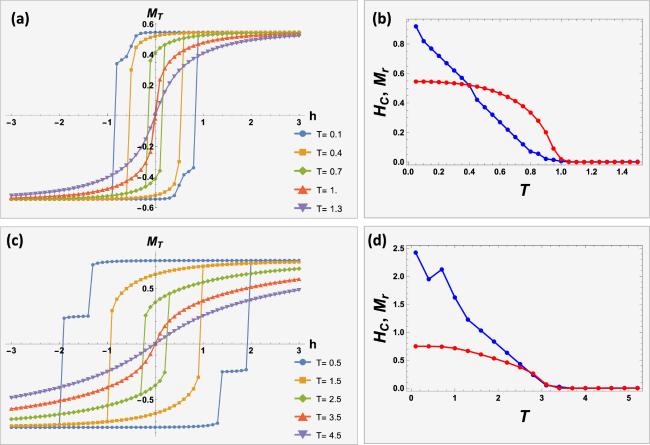

7 presents the variation of hysteresis characteristics with temperature for both

pb = 0.1 and

pb = 1.0. It is evident that as the temperature rises, the area enclosed by the hysteresis loop narrows, and the

HC and

Mr decrease until the hysteresis disappears below the critical temperature, indicating the loss of ferromagnetic properties at lower temperatures. At colder temperatures, a single hysteresis loop with a rectangular shape is observed, as the magnetization quickly reaches saturation. This results in the system displaying hard magnetic characteristics with a broad hysteresis loop. As the temperature increases, the loops begin to round due to fluctuations. The magnetizations no longer saturate after completing a cycle, and the slope of the increase decreases with rising temperature. At higher temperatures, the system exhibits soft magnetic characteristics with a smaller hysteresis loop, where all moments fluctuate with a relaxation time that is shorter than the measuring time. Consequently, the magnetization decreases to a point where less magnetic field is required to reverse the magnetic moments. Similar hysteresis loop behavior has been noted in nanostructure systems within both theoretical and experimental frameworks. In figure

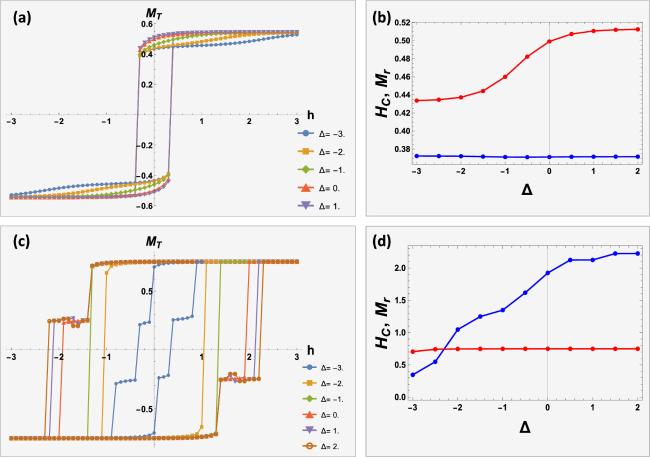

8, the influence of the crystal area parameter on the hysteresis characteristics is examined. For

pb = 0.1, the increase in crystal field did not alter the HLA, but the

Mr increased within a specific crystal field range. Conversely, for

pb = 1, the

HC increased as the HLA increased.