Nickel-based single-crystal superalloys are widely used in manufacturing turbine blades in aerospace engines due to their excellent high-temperature resistance to fatigue, creep, and oxidation [

1–

5]. Numerous solute atoms (e.g., Al, Ta, W, Mo, Cr, Co, Re, and Ru) were introduced into the nickel-based single-crystal superalloys [

6–

8]. They play roles in stabilizing the alloy structure, increasing the volume fraction of

γ′ phase, strengthening

γ and

γ′ phases, inhibiting the precipitation of harmful phases, and resisting oxidation [

9–

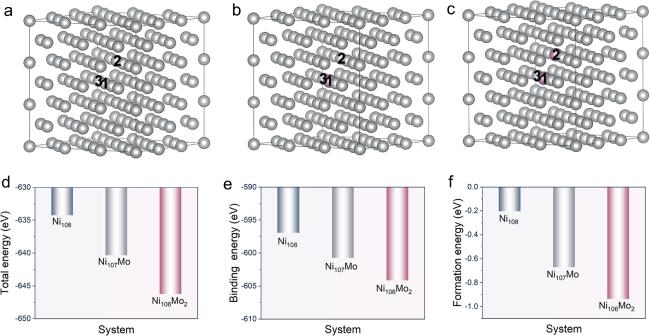

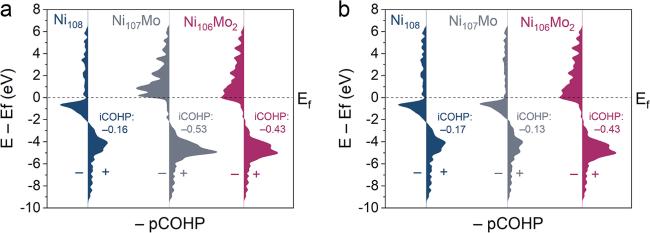

13]. Adding Mo will cause the local lattice distortion of the

γ phase, generating a large stress field and hindering the movement of dislocations, thereby achieving a solid solution-strengthening effect [

14–

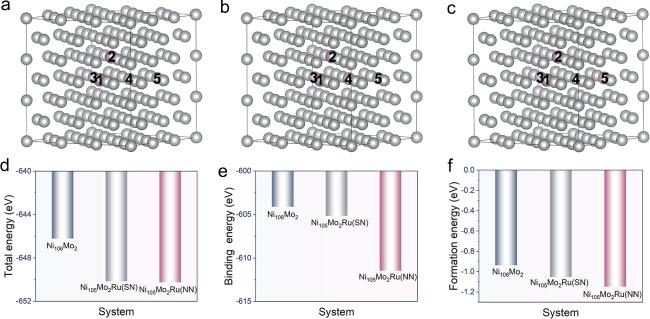

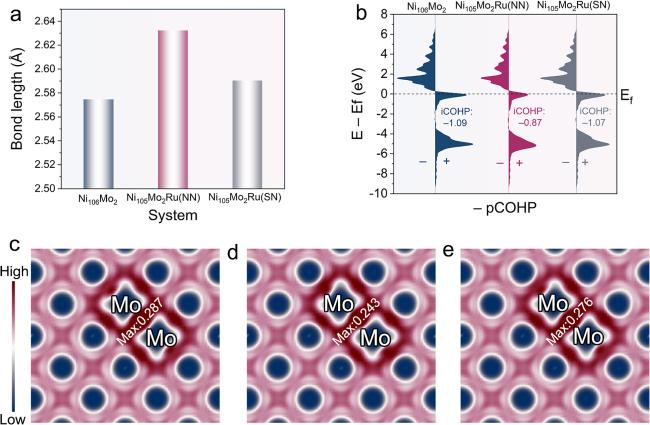

17]. The Ru element can suppress the precipitation of harmful phases in the matrix, reducing the occurrence of cracks and thereby improving the high-temperature structural stability of the alloy [

18–

21].