1. Introduction

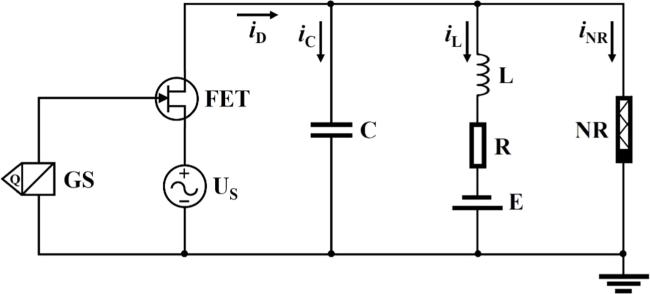

2. Model and scheme

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of a gas-sensitive neural circuit incorporated within a gas sensor and an FET. GS represents the gas sensor, C is a linear capacitor, L is a linear inductor, R is a linear resistor, E is a constant voltage source, US is an alternating voltage source, and NR is a nonlinear resistor. Gas sensor is considered a voltage source. |

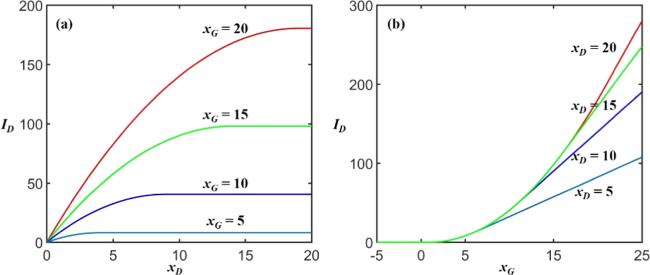

Figure 2. Typical electrical characteristics of an ideal FET with $K=1,$ $\eta =1$ and ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$. |

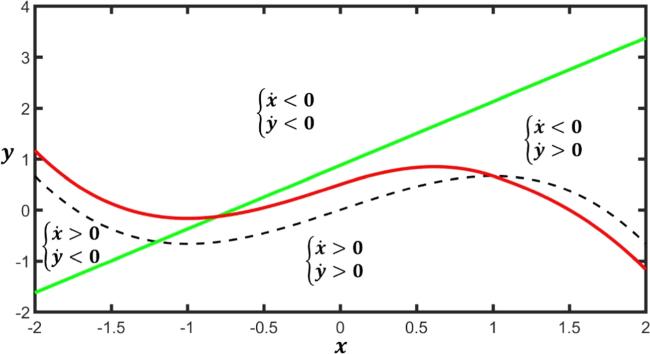

Figure 3. Fixed point analysis of system (6). Parameters are taken as $a=0.7,$ $b=0.8,$ $c=0.1,$ ${u}_{{\rm{s}}}=1,$ $K=1,$ ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2,$ ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1\,$and $\eta =1$ . |

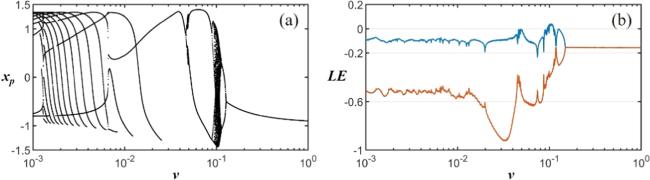

3. Numerical results and discussion

Figure 4. Bifurcation diagram and Lyapunov exponents of the gas-sensitive neural circuit with initial values ($0.1,$ $0.3$). Parameters are taken as $a=0.7,$ $b=0.8,$ $c=0.1,$ ${u}_{{\rm{s}}}=1,$ $K=1,$ ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2,$ ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and $\eta =1.$ ${x}_{{\rm{p}}}$ is the peak value of signal $x$ and LE is the Lyapunov exponent. |

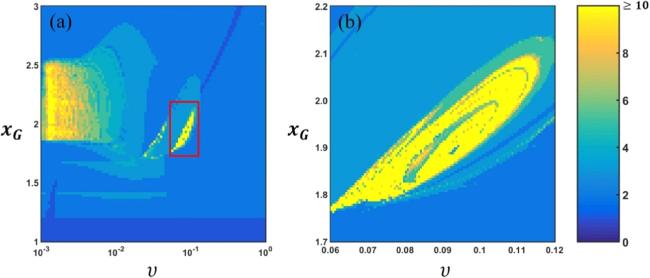

Figure 5. Dual parameter bifurcation diagram with gate voltage and frequency. Parameters are taken as $a=0.7,$ $b=0.8,$ $c=0.1,$ ${u}_{{\rm{s}}}=1,$ $K=1,$ ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1,$ $\eta =1$ and initial values ($0.1,$ $0.3$). Each color represents the number of peaks with different values. (a) Dual parameter bifurcation diagram, (b) the local enlarged drawing of the area enclosed by the red box. |

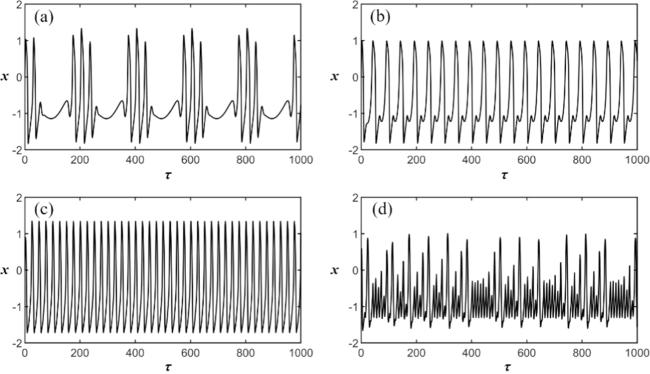

Figure 6. Time evolution of signal x by applying different frequencies to the alternating voltage source. Parameters are $a=0.7,$ $b=0.8,$ $c=0.1,$ ${u}_{{\rm{s}}}=1,$ $K=1,$ ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2,$ ${x}_{T}=1,$ $\eta =1,$ and initial values ($0.1,$ $0.3$). (a) Bursting mode with $\nu =0.005,$ (b) spiking mode with $\nu =0.02,$ (c) periodic firing mode with $\nu =0.04\,$and (d) chaotic mode with $\nu =0.1$. |

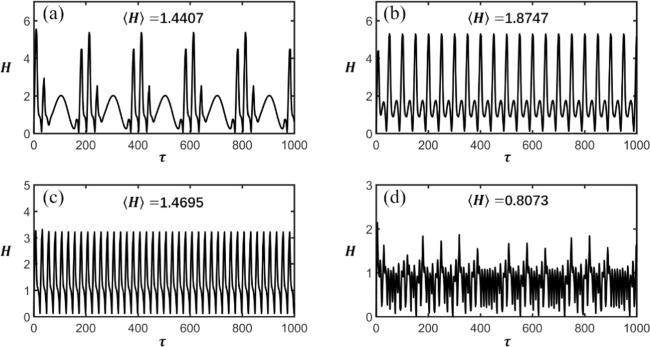

Figure 7. Time evolution of Hamiltonian energy with different frequencies. Parameters are $a=0.7,$ $b=0.8,$ $c=0.1,$ ${u}_{{\rm{s}}}=1,$ $K=1,$ ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2,$ ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1,$ $\eta =1$ and initial values ($0.1,$ $0.3$). (a) $\nu =0.005,$ (b) $\nu =0.02,$ (c) $\nu =0.04$ and (d) $\nu =0.1$. |

3.1. The bursting mode

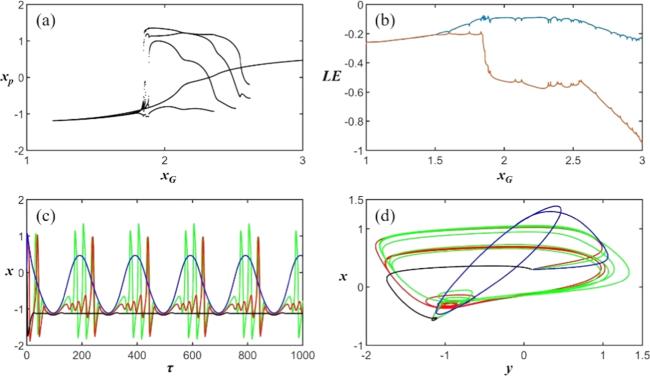

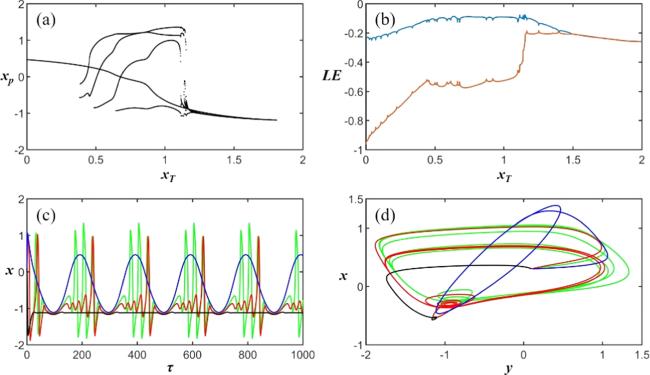

Figure 8. State in the bursting mode with different gate voltages. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and $\eta =1.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Black color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=1.5,$ red color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=1.85,$ green color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2$ and blue color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=3$. |

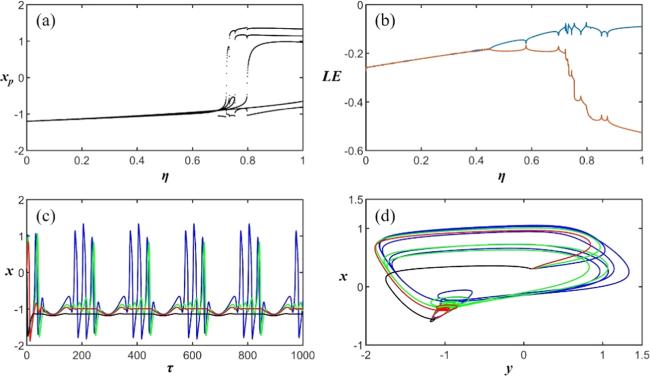

Figure 9. State in the bursting mode with different threshold voltages. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2$ and $\eta =1.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Blue color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=0,$ green color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1,$ red color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1.15$ and black color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1.5$. |

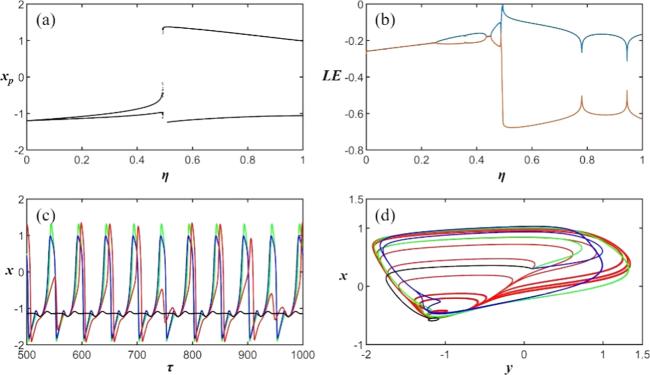

Figure 10. State in the bursting mode with different activation coefficients. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Black color represents $\eta =0.2,$ red color represents $\eta =0.6,$ green color represents $\eta =0.73$ and blue color represents $\eta =1$. |

3.2. The spiking mode

Figure 11. State in the spiking mode with different gate voltages. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and $\eta =1.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Black color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=1.5,$ red color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=1.704,$ green color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2$ and blue color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=3$. |

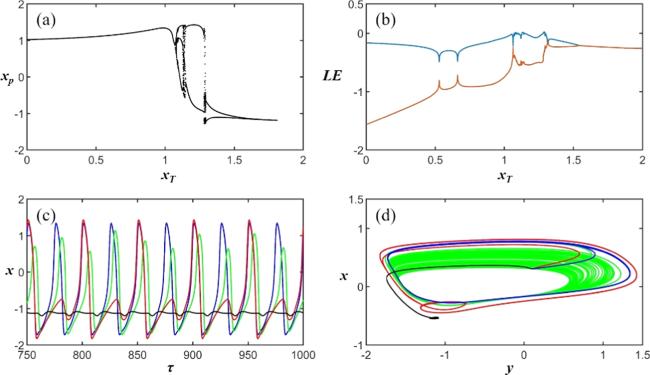

Figure 12. State in the spiking mode with different threshold voltages. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2$ and $\eta =1.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Blue color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=0,$ green color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1,$ red color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1.296$ and black color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1.5$. |

Figure 13. State in the spiking mode with different activation coefficients. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Black color represents $\eta =0.2,$ red color represents $\eta =0.4936,$ green color represents $\eta =0.6$ and blue color represents $\eta =1$. |

3.3. The periodic firing mode

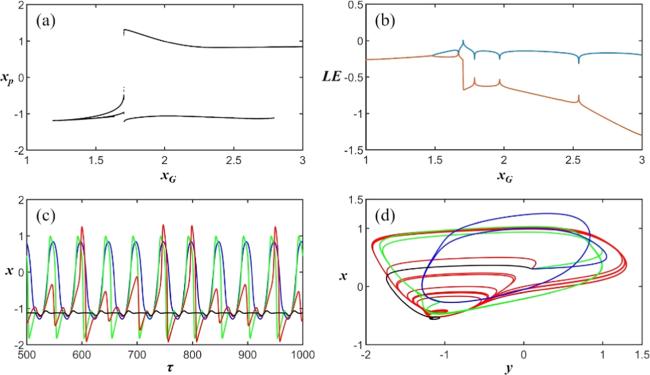

Figure 14. State in the periodic firing mode with different gate voltages. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and $\eta =1.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Black color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=1.5,$ red color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=1.709,$ green color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=1.8$ and blue color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2$. |

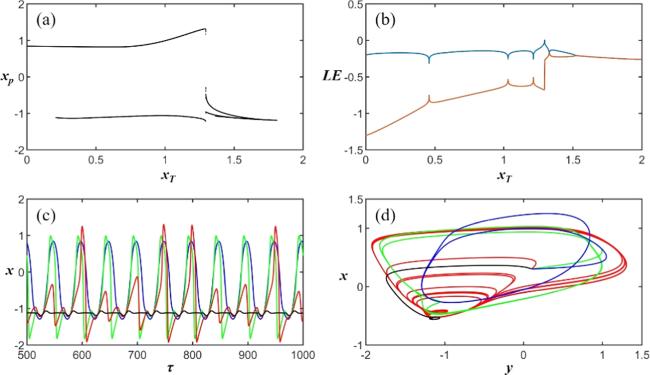

Figure 15. State in the periodic firing mode with different threshold voltages. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2$ and $\eta =1.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Blue color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1,$ green color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1.081,$ red color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1.2$ and black color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1.5$. |

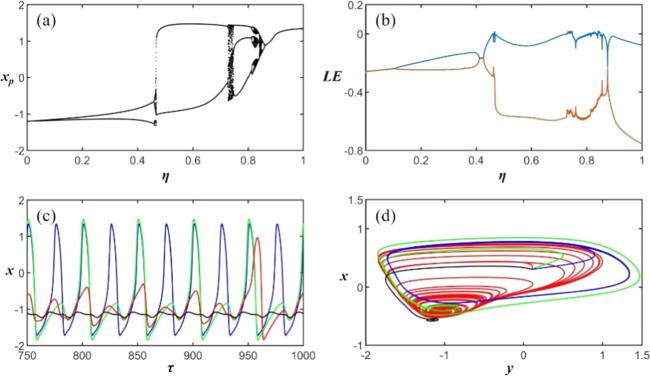

Figure 16. State in the periodic firing mode with different activation coefficients. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Black color represents $\eta =0.2,$ red color represents $\eta =0.467,$ green color represents $\eta =0.6$ and blue color represents $\eta =1$. |

3.4. The chaotic mode

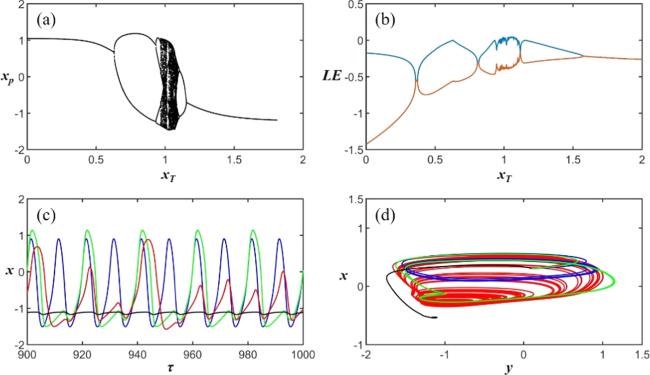

Figure 17. State in chaotic mode with different gate voltages. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and $\eta =1.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Black color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=1.5,$ red color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=1.85,$ green color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2$ and blue color represents ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2.5$. |

Figure 18. State in chaotic mode with different threshold voltages. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2$ and $\eta =1.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Blue color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=0.5,$ green color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=0.85,$ red color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and black color represents ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1.5$. |

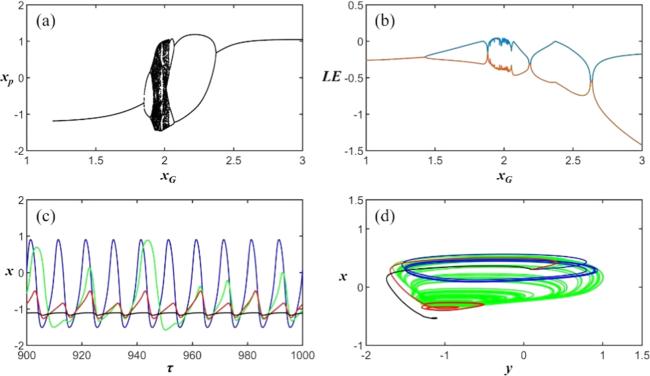

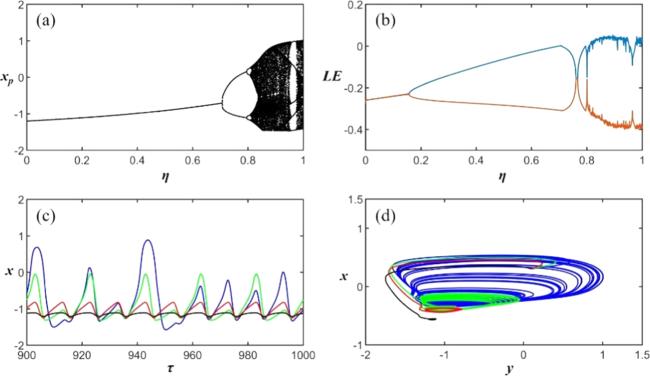

Figure 19. State in chaotic mode with different activation coefficients. Fixed parameters ${x}_{{\rm{T}}}=1$ and ${x}_{{\rm{G}}}=2.$ (a) Bifurcation diagram, (b) Lyapunov exponent, (c) time evolution of signal $x$ and (d) attractors. Black color represents $\eta =0.2,$ red color represents $\eta =0.6,$ green color represents $\eta =0.75$ and blue color represents $\eta =1$. |