1. Introduction

2. Basic formalism of matter creation

3. Basic field equations

4. VGCG model with matter creation

5. Particular solution

6. Observational data

6.1. Baryon acoustic oscillations

Table 1. The constraints on the parameters of the VGCG and VCG models with matter creation and the ΛCDM model. The combined dataset of BAO + CC + SC is refereed as ‘BASE'. |

| Model | Parameters | BASE | BASE + R21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| H0 [kms−1Mpc−1] | ${69.791}_{-1.070}^{+1.008}$ | ${71.432}_{-1.038}^{+1.111}$ | |

| ΛCDM | Ωm | ${0.271}_{-0.016}^{+0.018}$ | ${0.274}_{-0.018}^{+0.015}$ |

| ΩΛ | ${0.721}_{-0.027}^{+0.023}$ | ${0.726}_{-0.022}^{+0.022}$ | |

| | |||

| H0 [kms−1Mpc−1] | ${69.649}_{-2.379}^{+1.265}$ | ${72.674}_{-0.758}^{+0.355}$ | |

| Ωb | ${0.021}_{-0.019}^{+0.012}$ | ${0.020}_{-0.019}^{+0.011}$ | |

| VGCG | As | ${0.758}_{-0.056}^{+0.027}$ | ${0.767}_{-0.046}^{+0.026}$ |

| β | ${0.290}_{-0.254}^{+0.166}$ | ${0.260}_{-0.241}^{+0.155}$ | |

| n | ${0.114}_{-0.110}^{+0.090}$ | ${0.119}_{-0.114}^{+0.091}$ | |

| α | ${0.509}_{-0.457}^{+0.332}$ | ${0.450}_{-0.392}^{+0.284}$ | |

| | |||

| H0 [kms−1Mpc−1] | ${69.638}_{-2.491}^{+1.207}$ | ${72.680}_{-0.775}^{+0.399}$ | |

| Ωb | ${0.020}_{-0.011}^{+0.013}$ | ${0.020}_{-0.016}^{+0.013}$ | |

| VCG | As | ${0.756}_{-0.046}^{+0.021}$ | ${0.765}_{-0.022}^{+0.021}$ |

| β | ${0.484}_{-0.025}^{+0.012}$ | ${0.481}_{-0.032}^{+0.011}$ | |

| n | ${0.105}_{-0.105}^{+0.088}$ | ${0.109}_{-0.105}^{+0.088}$ | |

6.2. Cosmic chronometers

6.3. Standard candles

6.4. R21 measurement

7. Results and discussion

Figure 1. 2D contour at 68.3% and 95.4% confidence levels for the ΛCDM model using BASE and BASE + R21 datasets. |

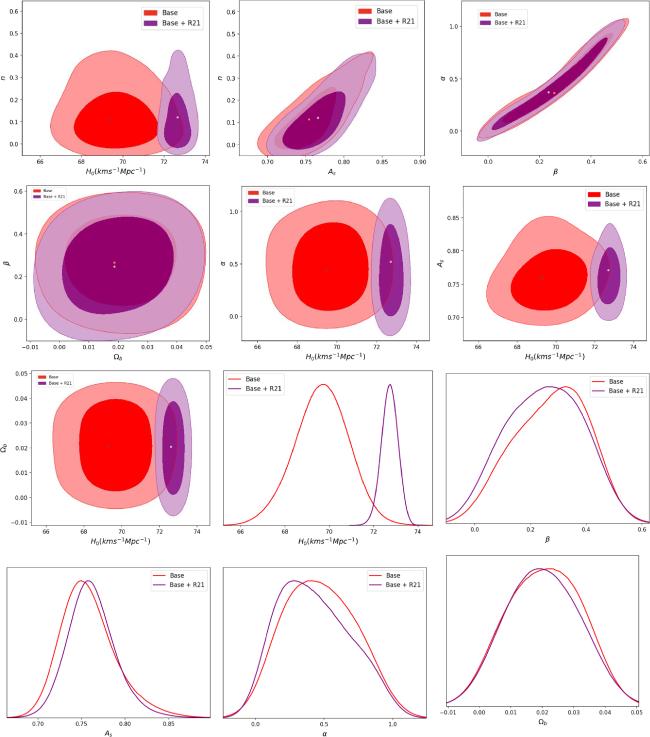

Figure 2. 2D contours at 68.3% and 95.4% confidence levels for pairs (n, H0), (n, As), (α, β), (β, Ωb), (α, H0), (As, H0) and (Ωb, H0), and 1D posterior distribution of H0, β, As, α and Ωb for the VGCG model with matter creation using BASE and BASE+R21 datasets, repsectively. |

Figure 3. 2D contour at 68.3% and 95.4% confidence levels for pairs (β, H0), (As, H0), (β, As), (As, Ωb), (Ωb, H0), (n, H0), (n, As) and (β, Ωb), and 1D posterior distribution of H0, As, β and Ωb for the VCG model with matter creation using BASE and BASE+R21 datasets. |

Table 2. The constraints on the parameters of VGCG and VCG models without matter creation. The combined dataset of BAO + CC + SC is referred to as ‘BASE'. |

| Model | Parameters | BASE | BASE + R21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| H0 [kms−1Mpc−1] | ${69.674}_{-0.563}^{+1.217}$ | ${72.670}_{-0.412}^{+1.326}$ | |

| Ωb | ${0.020}_{-0.024}^{+0.015}$ | ${0.020}_{-0.015}^{+0.014}$ | |

| VGCG | As | ${0.767}_{-0.033}^{+0.012}$ | ${0.770}_{-0.016}^{+0.021}$ |

| n | ${0.129}_{-0.026}^{+0.101}$ | ${0.116}_{-0.011}^{+0.004}$ | |

| α | ${0.040}_{-0.017}^{+0.021}$ | ${0.042}_{-0.061}^{+0.072}$ | |

| | |||

| H0 [kms−1Mpc−1] | ${69.870}_{-0.365}^{+1.133}$ | ${72.640}_{-0.352}^{+1.362}$ | |

| Ωb | ${0.030}_{-0.036}^{+0.025}$ | ${0.030}_{-0.021}^{+0.005}$ | |

| VCG | As | ${0.994}_{-0.002}^{+0.001}$ | ${0.994}_{-0.021}^{+0.017}$ |

| n | ${1.140}_{-0.101}^{+0.032}$ | ${0.128}_{-0.035}^{+0.041}$ | |

7.1. Evolution of cosmological parameters

Figure 4. Evolution of H(z) with redshift z in VGCG and VCG models with matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using the BASE dataset. The grey points with uncertainty bars corresponds to the H(z) sample. The black bold line represents the ΛCDM model. |

Figure 5. Evolution of H(z) with redshift z in VGCG and VCG models with matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using the BASE+R21 dataset. The grey points with uncertainty bars corresponds to the H(z) sample. The black bold line represents the ΛCDM model. |

Figure 6. Evolution of H(z) with redshift z in VGCG and VCG models without matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using the BASE dataset. The grey points with uncertainty bars corresponds to the H(z) sample. The black bold line represents the ΛCDM model. |

Figure 7. Evolution of H(z) with redshift z in VGCG and VCG models without matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using the BASE+R21 dataset. The grey points with uncertainty bars corresponds to the H(z) sample. The black bold line represents the ΛCDM model. |

Figure 8. Evolution of q(z) with z in VGCG and VCG models with matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using the BASE dataset. The dots represent the present value of q(z). |

Figure 9. Evolution of q(z) with z in VGCG and VCG models with matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using the BASE+R21 dataset. The dots represent the present value of q(z). |

Table 3. The present values of different cosmological and geometrical parameters of ΛCDM, VGCG and VCG models with matter creation. |

| Models → | ΛCDM | VGCG | VCG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parametrs | BASE | +R21 | BASE | +R21 | BASE | +R21 |

| ztr | ${0.692}_{-0.029}^{+0.034}$ | ${0.689}_{-0.033}^{+0.028}$ | ${0.610}_{-0.022}^{+0.030}$ | ${0.631}_{-0.023}^{+0.037}$ | ${0.674}_{-0.016}^{+0.029}$ | ${0.687}_{-0.031}^{+0.036}$ |

| q0 | $-{0.591}_{-0.01}^{+0.01}$ | $-{0.590}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ | $-{0.541}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ | $-{0.542}_{-0.05}^{+0.05}$ | $-{0.553}_{-0.03}^{+0.03}$ | $-{0.555}_{-0.03}^{+0.03}$ |

| w0 | $-{0.726}_{-0.04}^{+0.04}$ | $-{0.728}_{-0.01}^{+0.01}$ | $-{0.730}_{-0.11}^{+0.11}$ | $-{0.740}_{-0.13}^{+0.13}$ | $-{0.721}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ | $-{0.728}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ |

| t0 (Gyr) | ${13.73}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ | ${13.76}_{-0.04}^{+0.04}$ | ${13.91}_{-0.03}^{+0.03}$ | ${13.94}_{-0.07}^{+0.07}$ | ${13.87}_{-0.03}^{+0.03}$ | ${13.89}_{-0.01}^{+0.01}$ |

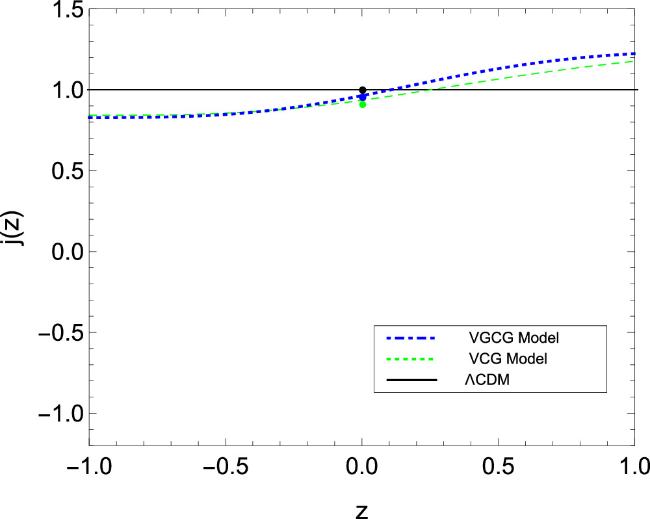

| j0 | 1 | 1 | ${0.933}_{-0.21}^{+0.21}$ | ${0.941}_{-0.10}^{+0.10}$ | ${0.979}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ | ${0.966}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ |

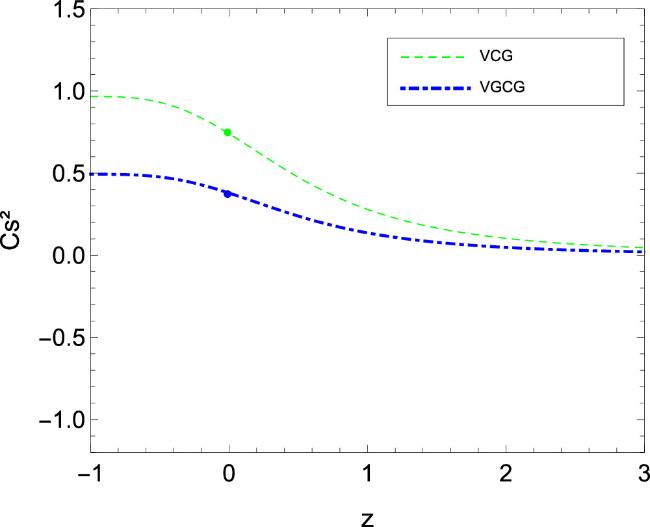

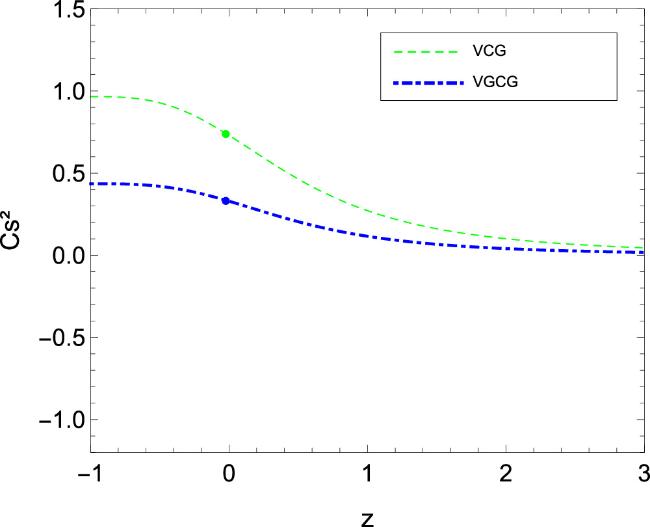

| ${C}_{s}^{2}$ | — | — | 0.329 | 0.379 | 0.730 | 0.740 |

Table 4. The present values of different cosmological and geometrical parameters of VGCG and VCG models without matter creation. |

| Models → | VGCG | VCG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parametrs | BASE | +R21 | BASE | +R21 |

| ztr | ${0.689}_{-0.021}^{+0.023}$ | ${0.694}_{-0.024}^{+0.019}$ | ${0.955}_{-0.023}^{+0.018}$ | ${0.922}_{-0.014}^{+0.018}$ |

| q0 | $-{0.652}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ | $-{0.617}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ | $-{0.590}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ | $-{0.573}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ |

| w0 | $-{0.589}_{-0.11}^{+0.11}$ | $-{0.595}_{-0.15}^{+0.15}$ | $-{0.838}_{-0.01}^{+0.01}$ | $-{0.842}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ |

| t0 (Gyr) | ${13.77}_{-0.01}^{+0.01}$ | ${13.83}_{-0.03}^{+0.03}$ | ${13.91}_{-0.02}^{+0.02}$ | ${13.93}_{-0.01}^{+0.01}$ |

| j0 | ${0.959}_{-0.19}^{+0.19}$ | ${0.742}_{-0.21}^{+0.21}$ | ${0.892}_{-0.11}^{+0.11}$ | ${1.01}_{-0.12}^{+0.12}$ |

| ${C}_{s}^{2}$ | 0.414 | 0.490 | 0.781 | 0.805 |

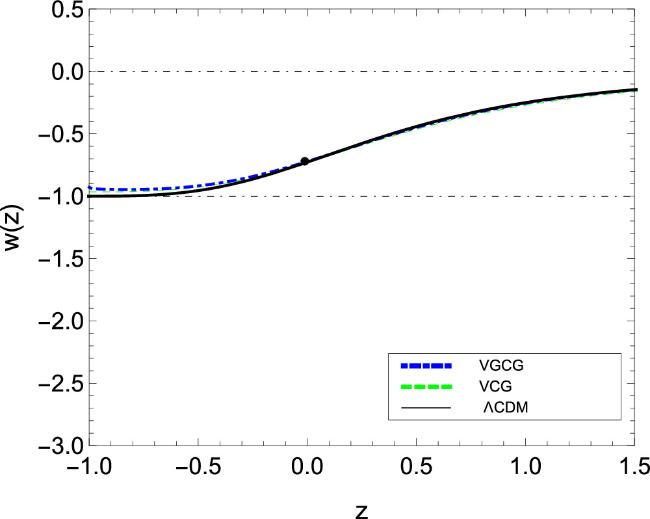

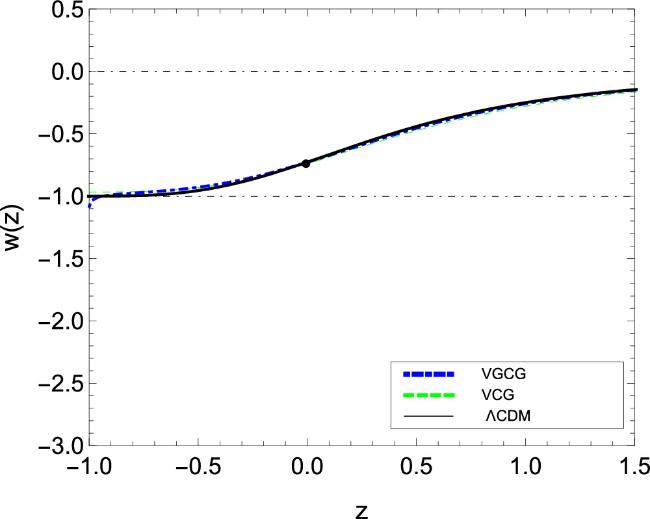

Figure 10. Evolution of w(z) with z in VGCG and VCG models with matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using the BASE dataset. The dots represent the present value of w(z). |

Figure 11. Evolution of w(z) with z in VGCG and VCG models with matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using the BASE+R21 dataset. The dots represent the present value of w(z). |

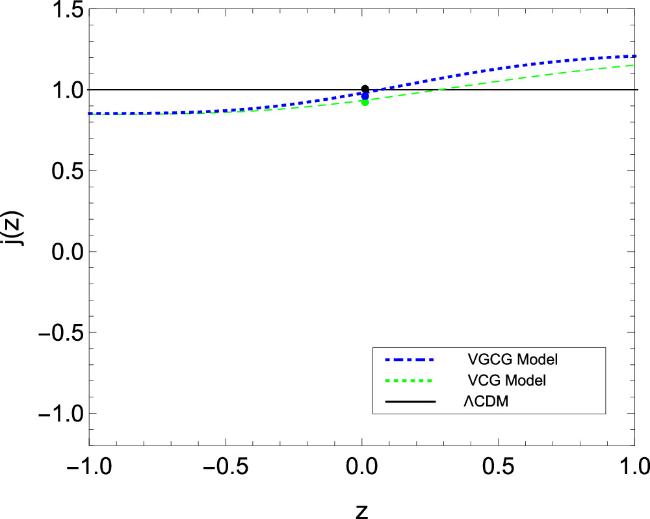

Figure 12. Trajectories of j(z) for VGCG and VCG models with matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using best-fit values from the BASE dataset. The dots represent the present value of j0. |

Figure 13. Trajectories of j(z) for VGCG and VCG models with matter creation, and the ΛCDM model using the BASE+R21 datasets The dots represent the present value of j0. |

7.2. Stability of the model

Figure 14. Trajectories of ${{ \mathcal C }}_{s}^{2}$ for VGCG and VCG models with matter creation using best-fit values of the BASE dataset. |

Figure 15. Trajectories of ${{ \mathcal C }}_{s}^{2}$ for VGCG and VCG models with matter creation using best-fit values of the BASE+R21 dataset. |

7.3. Model selection

Table 5. ${\chi }_{{red}}^{2}$, AIC (BIC), Bayesian evidence and Bayes factor values for ΛCDM, VGCG and VCG models with matter creation. Here the ΛCDM model is taken as a reference model to calculate ΔAIC, ΔBIC and $\mathrm{ln}B$. |

| Model | Parameters | BASE | +R21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}$ | 253.92 | 254.17 | |

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}/{dof}$ | 0.94 | 0.94 | |

| ΛCDM | AIC | 260.01 | 260.26 |

| BIC | 270.75 | 271.00 | |

| $\mathrm{ln}E(M1)$ | −123.824 | −124.116 | |

| | |||

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}$ | 255.51 | 257.74 | |

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}/{dof}$ | 0.965 | 0.953 | |

| AIC | 267.82 | 270.05 | |

| VGCG | BIC | 289.16 | 291.41 |

| ΔAIC | 7.81 | 9.79 | |

| ΔBIC | 18.41 | 20.41 | |

| $\mathrm{ln}\ E(M2)$ | −125.938 | -126.099 | |

| lnB12 | 2.114 | 1.983 | |

| Evidence interpretation | positive | positive | |

| | |||

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}$ | 254.59 | 257.63 | |

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}/{dof}$ | 0.95 | 0.96 | |

| AIC | 264.81 | 267.86 | |

| VCG | BIC | 282.64 | 285.70 |

| ΔAIC | 4.80 | 7.60 | |

| ΔBIC | 11.89 | 14.70 | |

| $\mathrm{ln}E(M2)$ | −126.513 | −126.697 | |

| lnB12 | 2.689 | 2.581 | |

| Evidence interpretation | moderate | moderate | |

Table 6. ${\chi }_{{red}}^{2}$, AIC (BIC), Bayesian evidence and Bayes factor values for VGCG and VCG models without matter creation. Here, the ΛCDM model is taken as a reference model to calculate ΔAIC, ΔBIC and $\mathrm{ln}B$. |

| Model | Parameters | BASE | +R21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}$ | 255.32 | 257.94 | |

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}/{dof}$ | 0.956 | 0.962 | |

| AIC | 265.54 | 268.16 | |

| VGCG | BIC | 283.36 | 286.01 |

| ΔAIC | 5.53 | 7.92 | |

| ΔBIC | 12.61 | 15.01 | |

| $\mathrm{ln}E(M2)$ | −126.095 | −125.486 | |

| lnB12 | 2.271 | 1.370 | |

| Evidence interpretation | Positive | Positive | |

| | |||

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}$ | 254.21 | 255.76 | |

| ${\chi }_{\min }^{2}/{dof}$ | 0.959 | 0.950 | |

| AIC | 262.36 | 263.91 | |

| VCG | BIC | 276.65 | 278.21 |

| ΔAIC | 2.35 | 3.67 | |

| ΔBIC | 5.90 | 7.21 | |

| $\mathrm{ln}E(M2)$ | −132.818 | −132.434 | |

| lnB12 | 8.994 | 8.318 | |

| Evidence interpretation | Decisive | Decisive | |

7.4. Bayesian evidence analysis

Table 7. Jeffrey' Interpretive scales for the strength of evidence when comparing two models, M1 and M2. |

| lnB12 | Strength of evidence |

|---|---|

| <1 | Inconclusive |

| 1.0 − 2.5 | Positive evidence |

| 2.5 − 5.0 | Moderate evidence |

| >5 | Decisive |