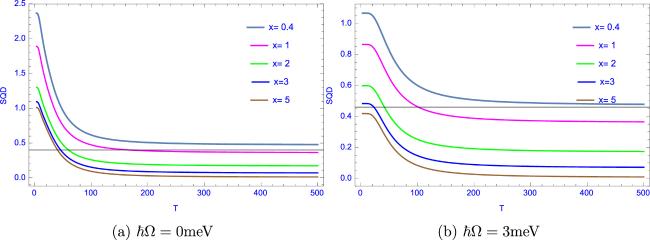

Figure

2(a) shows that the quantity of super quantum discord decreases whenever we increase the electric field parameter

ℏΩ. Physically, this decrease is attributed to the alignment of all dipoles in a singular direction under the influence of an external electric field. This alignment results in an intensified dipole-dipole repulsive interaction, precipitating a reduction in Coulomb-induced correlations [

29]. Furthermore, it shows that the pace of this decrease is broadly influenced by the variation of the measurement strength. Interestingly, in this figure, we observe that the super quantum discord attains notably smaller values at larger

x even when the electric field is deactivated, which is particularly intriguing because under typical conditions, one would anticipate it to reach its maximum value. Additionally, we observe that at smaller values of

x, this super quantum correlation diminishes slowly with the increase of the electric field parameter, and even for large values of this parameter its quantity remains considerable. These observations imply that weak measurement slows up the influence of external electric field on super quantum correlation. Moving into figure

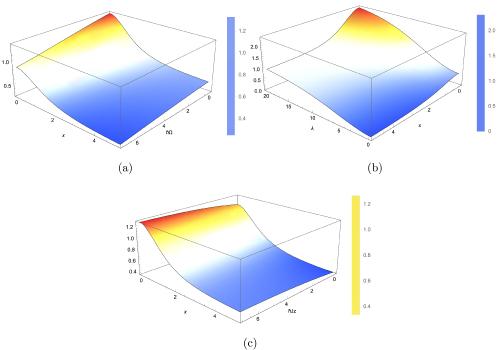

2(b), it is seen that increasing the Förster interaction parameter

λ amplifies the super quantum correlation in the system, a consequence of the heightened exciton–exciton interaction. Further, it is seen that for higher measurement strength

x, this correlation vanishes whenever this parameter vanishes then increases until reaching its stabilized value, however, for vanishing or weak measurement strength

x, it is present even for vanishing Förster interaction and it attains its zenith for large values of this latter. Besides, figure

2(c) illustrates that an increase in the exciton–exciton dipole interaction energy enhances the super quantum discord (SQD) between the excitonic qubits of the system. Furthermore, it demonstrates that for smaller or vanishing values of the parameter

x, this correlation reaches its maximum. Interestingly, despite the decrease in the coupling

ℏJz, it manages to maintain its higher values. However, as this parameter attains higher values, the super quantum discord (SQD) quantity reaches its minimum, even in the presence of larger coupling

ℏJz. As a matter of fact, from the three plots of figure

2 we state that the influence of varying the measurement strength

x significantly surpasses the effects of Förster interaction, exciton–exciton dipole interaction energy and external electric field on the system. In light of these findings, we deem that our system and its exciton–exciton interactions can be controlled by manipulating the measurement strength

x parameter.