1. Introduction

2. Model and basic theory

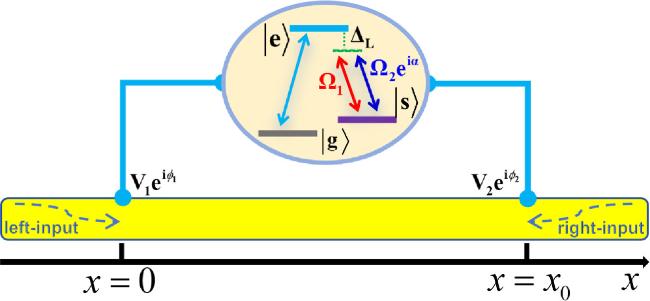

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the giant waveguide-QED system. Giant atom contains a ground state $\left|g\right\rangle ,$ an excited state $\left|e\right\rangle $ and a metastable state $\left|s\right\rangle .$ Transition between states $\left|e\right\rangle $ and $\left|g\right\rangle $ is coupled by the waveguide mode at two separate points $x=0$ and $x={x}_{0}$ with coupling strengths ${V}_{j}{{\rm{e}}}^{{\rm{i}}{\phi }_{j}}$($j=1,2$) and ${\phi }_{j=1,2}$ are the corresponding coupling phases. Transition between states $\left|e\right\rangle $ and $\left|s\right\rangle $ is driven by two classical fields with detuning ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{L}.$ ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{1},$ ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{2}$ and $\alpha $ are the corresponding Rabi frequencies and phase difference between the two driven lasers. |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Nonreciprocal single-photon scattering with ${\rm{\Omega }}=0$

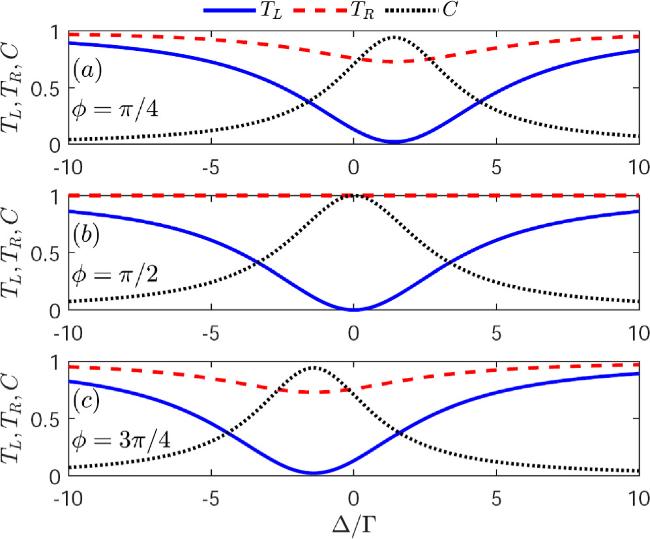

Figure 2. Transmission probabilities ${T}_{L},$ ${T}_{R}$ and the contrast ratio $C$ as a function of the frequency detuning ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ for different phase differences $\phi .$ Other common parameters are ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{1}={{\rm{\Omega }}}_{2}=0,$ $\theta =\pi /2$ and ${\gamma }_{e}=4{\rm{\Gamma }}$. |

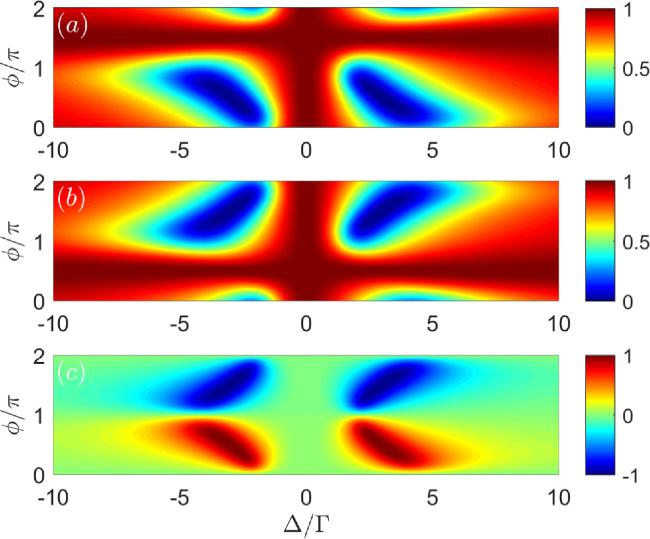

Figure 3. Contour map of the transmission probabilities ${T}_{L},$ ${T}_{R}$ and the contrast ratio $C$ as the function of both ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ and $\phi /\pi $ in (a), (b) and (c), respectively. Other common parameters are the same as those shown in figure 2. |

3.2. Nonreciprocal single-photon scattering with ${\rm{\Omega }}\ne 0$

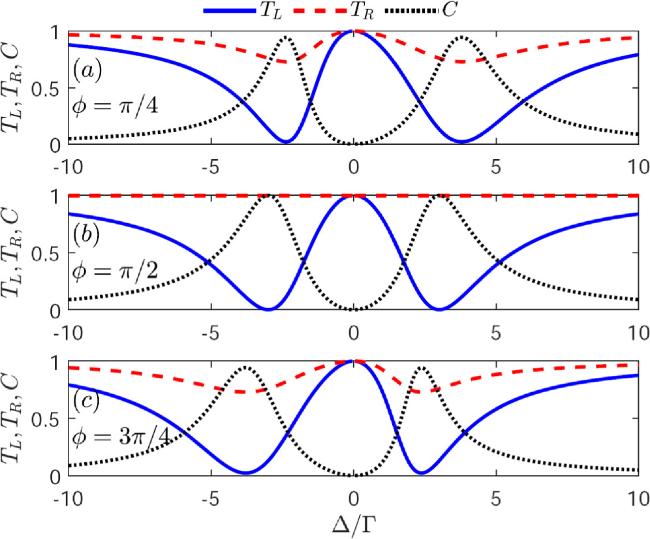

Figure 4. Transmission probabilities ${T}_{L},$ ${T}_{R}$ and the contrast ratio $C$ as a function of the frequency detuning ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ for different phase differences $\phi .$ Other common parameters are ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{1}=3{\rm{\Gamma }},$ ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{2}=0,$ $\theta =\pi /2$ and ${\gamma }_{e}=4{\rm{\Gamma }}$. |

Figure 5. Contour map of the transmission probabilities ${T}_{L},$ ${T}_{R}$ and the contrast ratio $C$ as the function of both ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ and $\phi /\pi $ in (a), (b) and (c), respectively. Other common parameters are the same as those shown in figure 4. |

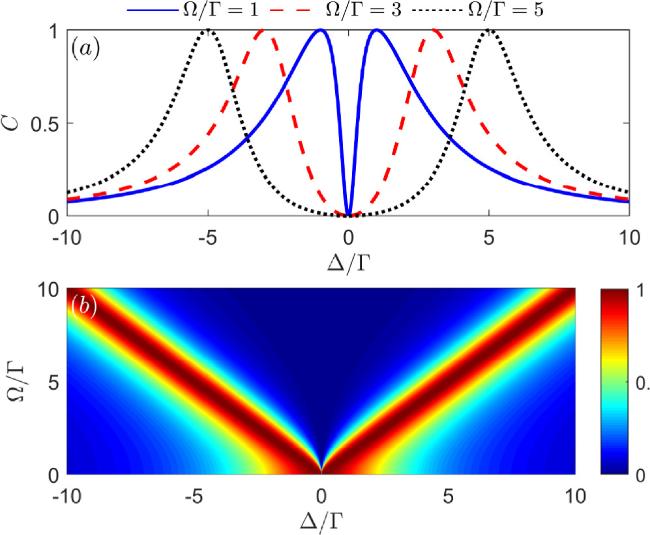

Figure 6. Contrast ratio C as a function of the detuning ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ for different Rabi frequencies in (a) and the corresponding contour map with respect to ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ and ${\rm{\Omega }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ in (b). Other common parameters are $\phi =\theta =\pi /2,$ ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{2}=0$ and ${\gamma }_{e}=4{\rm{\Gamma }}$. |

Figure 7. Contrast ratio as a function of the detuning ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ and phase difference $\alpha $ in (a) and the corresponding profiles of the contour map with different $\alpha $ in (b). Other common parameters are $\phi =\theta =\pi /2,$ ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{2}={{\rm{\Omega }}}_{1}=3{\rm{\Gamma }}$ and ${\gamma }_{e}=4{\rm{\Gamma }}$. |

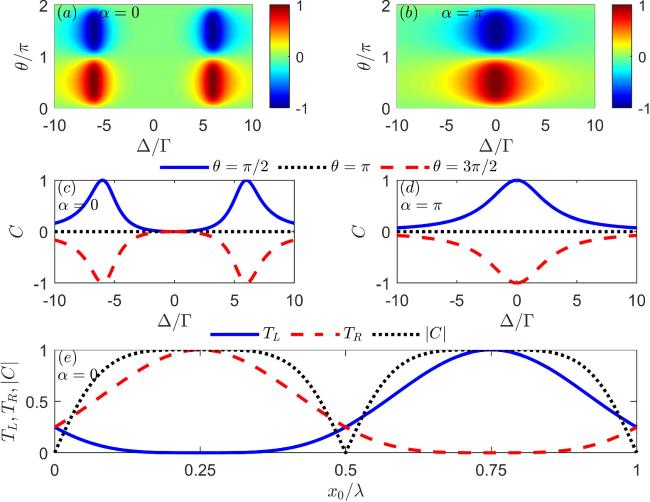

Figure 8. Contrast ratio $C$ versus detuning ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ and accumulated phase $\theta $ in (a) and (b), and the corresponding profiles of the contour map with different $\theta $ in (c) and (d). Transmission probabilities ${T}_{L},$ ${T}_{R}$ and the contrast ratio $\left|C\right|$ as a function of the distance between the two coupling points ${x}_{0}/\lambda $ with ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}=6$ in figure 8(e). Other common parameters are $\phi =\pi /2,$ ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{2}={{\rm{\Omega }}}_{1}=3{\rm{\Gamma }}$ and ${\gamma }_{e}=4{\rm{\Gamma }}$. |

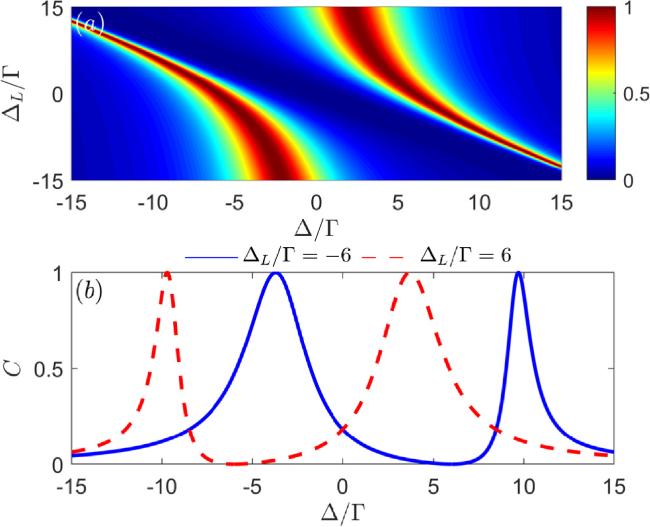

Figure 9. Contrast ratio $C$ as a function of the frequency detuning ${\rm{\Delta }}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ and driving detuning ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{L}/{\rm{\Gamma }}$ in (a), and the corresponding profiles of the contour map with different ${{\rm{\Delta }}}_{L}$ in (b). Other common parameters are $\phi =\theta =\pi /2,$ $\alpha =0,$ ${{\rm{\Omega }}}_{2}={{\rm{\Omega }}}_{1}=3{\rm{\Gamma }}$ and ${\gamma }_{e}=4{\rm{\Gamma }}$. |