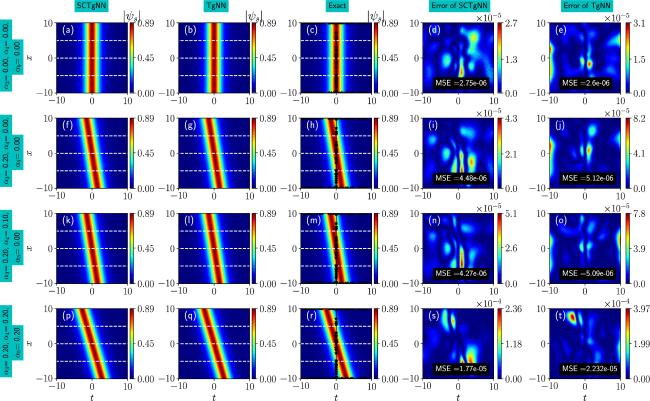

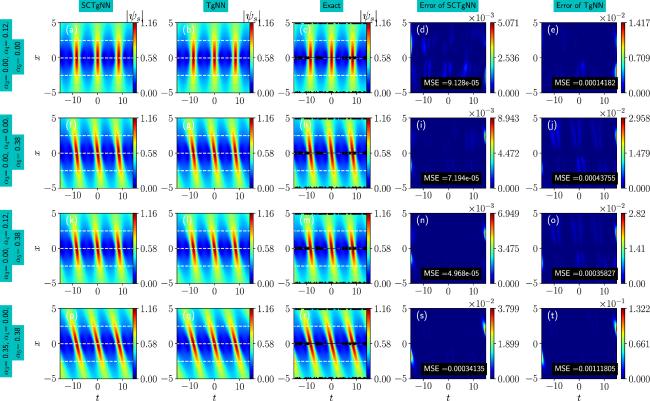

In figure

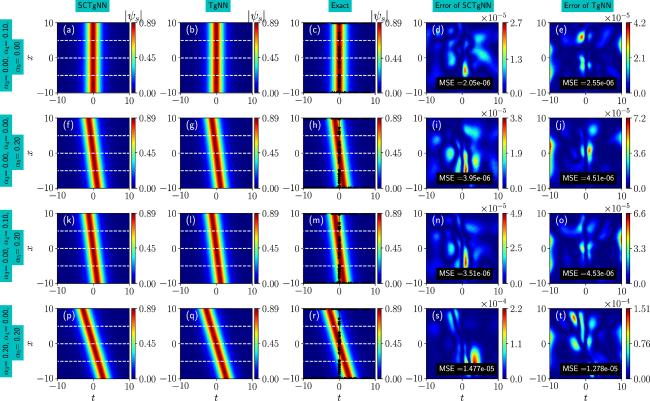

8, we present the results of the dynamical prediction of breather solutions and their error estimations using the SCTgNN and TgNN, where

α2 = 1 and

c = 1. Unlike solitons and rogue waves, breathers can be predicted using the following initial values when

x = 0. Here,

t ranges from −15 to 15 and

x ranges from −5 to 5, while the other

αi's remain the same. The figures in the first row (figures

8 (a)–(c)) represent the solution of the standard NLS equation, corresponding to

α3 =

α4 =

α5 = 0. In addition, figures

8 (d) and

(e) display the error diagram, highlighting the discrepancies between the SCTgNN and TgNN. Upon increasing the value of

α3 to 0.2, while maintaining the other parameters constant, we observe subtle changes in the orientation of the breathers, as depicted in figures

8 (f)–(h). The corresponding error diagrams are provided in figures

8 (i) and

(j). Furthermore, when we set

α4 = 0.1 and keep the parameters consistent with the previous case (figures

8 (f)–(h)), the width of the breathers undergoes a change, as shown in figures

8 (k)–(m). The error diagrams for this situation can be observed in figures

8(n) and

(o). Similarly, by introducing the fifth-order dispersion parameter (

α5 = 0.2) while maintaining the other parameters from the previous case, we again observe changes in the orientation of the breathers, as illustrated in figures

8 (p)–(r). The corresponding error diagrams are presented in figures

8(s) and

(t). In figures

8 (c), (h), (m) and

(r), the star markers indicate randomly chosen data points on the initial and boundary conditions. For our analysis, we used 2000 data points for each condition, including

α3,

α4 and

α5. Overall, the results demonstrate that the inclusion of higher-order dispersion parameters

α3,

α4 and

α5 in the standard NLS equation leads to changes in the width and orientation of the breathers. Similarly, the SCTgNN and TgNN models demonstrate superior error prediction capabilities, as illustrated in the MSE prediction figures. These findings indicate that the new SCTgNN and TgNN models excel at estimating the breather solution for the generalized NLS equation, with only a few minor errors. Figure

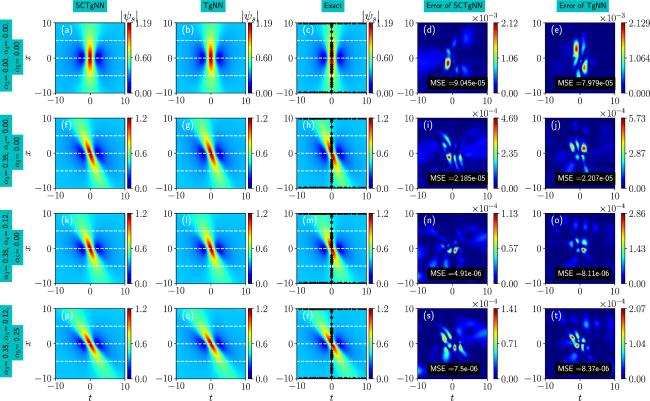

9 shows the results of breathers for the generalized NLS equation (

1) for four different sets of system parameters. The first two rows depict the LPD equations (figures

9 (a)–(e)) and the fifth-order NLS equations (figures

9 (f)–(j)). The last two rows represent the system's behavior with randomly chosen parameters. In the third row (figures

9 (k)-(o)), with parameters

α3 = 0,

α4 = 0.12 and

α5 = 0.38, the orientation of the breathers shows a slight deviation from the original. In the fourth row (figures

9 (p)–(t)), with different values of

α3 = 0.35,

α4 = 0 and

α5 = 0.38, the orientation change is more pronounced.