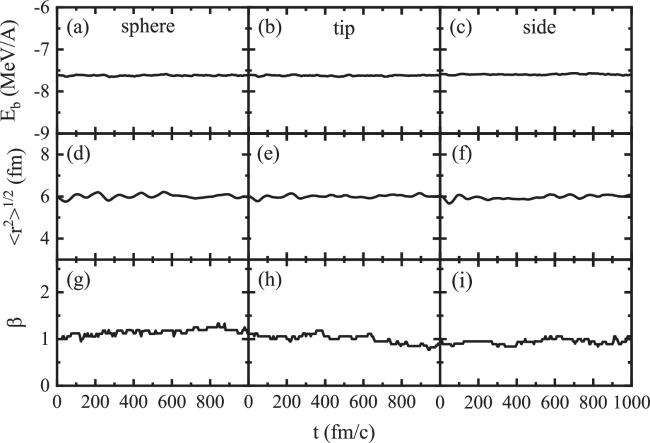

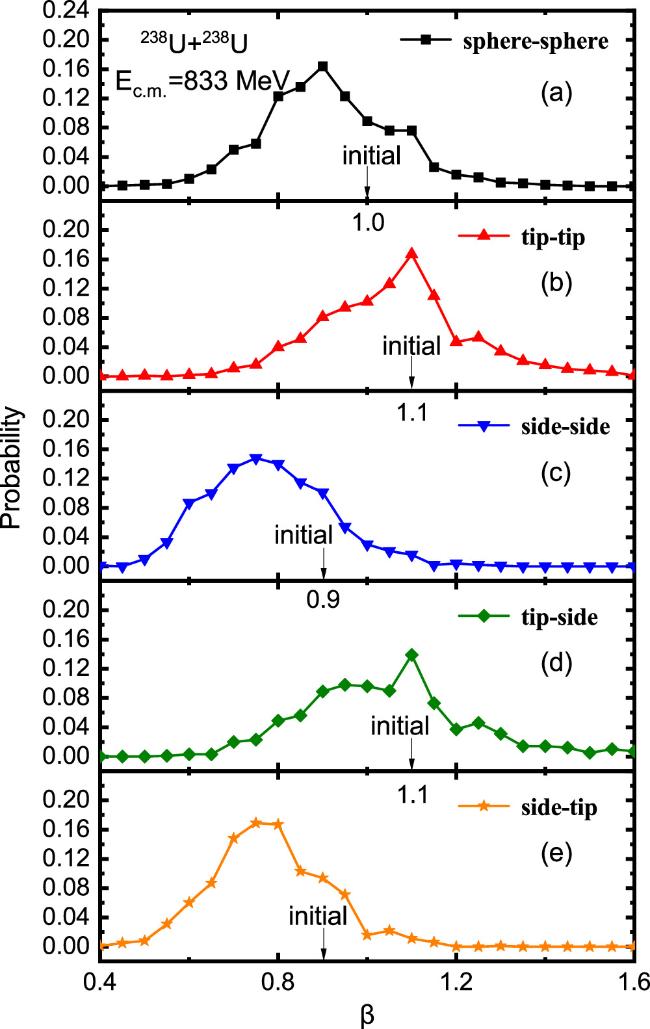

This section aims to statistically analyze the deformation physical quantity

β values of the projectile at the contact moment for all events to investigate the influence of the orientation effect on nuclear deformation. Figure

5 illustrates the probability distribution of

β value for the projectile at the contact moment in the

238U+

238U reaction with a collision parameter

b = 1 fm. The arrows indicate the initial

β value, which is the statistically averaged value obtained from all sampling events, and (a)–(e) denote the cases of the sphere–sphere, tip–tip, tip–side, side–side, and side–tip collisions, respectively. The most available

β values of the projectile for sphere-sphere, tip-tip, tip-side, side-side, and side-tip collisions are 0.9, 1.1, 1.05, 0.75, and 0.75, respectively, while the initial

β values in the sphere, tip orientation, and side orientation are 1.0, 1.1 and 0.9, respectively. This result indicates that the projectile retains its initial orientation characteristics to some extent at the contact moment. Meanwhile, the most available

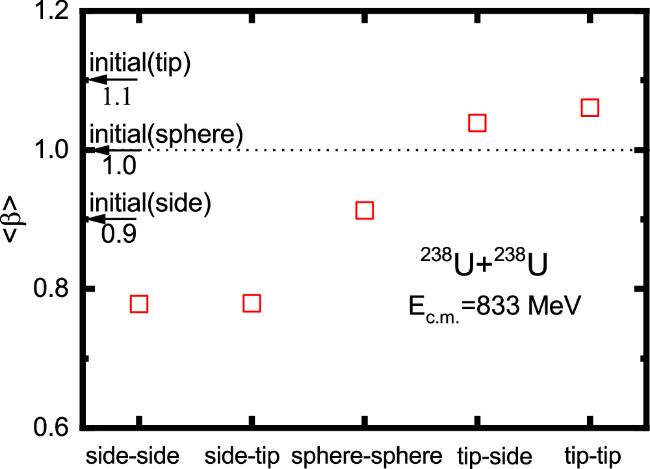

β value is lower than its initial value. This phenomenon is particularly evident in figure

6, which shows statistical average values of the

β. The average values of

β at the contact moment are 0.78, 0.78, 0.91, 1.04 and 1.06 in side–side, side–tip, sphere–sphere, tip–side, and tip–tip collisions, respectively; all of these values are lower than their respective initial values. This trend is mainly due to the Coulomb repulsion that causes the nuclei to suffer compression in the collision direction from the initial time to the contact moment. Additionally, upon analyzing figures

5(b) and (d), it can be found that the probability distributions of

β values show a similar shape, as well as the most available

β values and their corresponding locations are very similar. In these cases, the corresponding projectiles are in the tip orientation, and the targets are in the tip and side orientations. Similarly, in figures

5(c) and (e), the shapes of the probability distributions of

β, the most available values, and their locations are also very close. At this time, the corresponding projectile is in side orientation, and the target nuclei are in the side and tip orientations, respectively. These results indicate that the

β value of the projectile at the contact moment is less affected by the target orientation and vice versa. It can also be seen from figure

6 that statistical mean values of the

β are almost the same when the projectile is both in the tip orientation (side orientation).