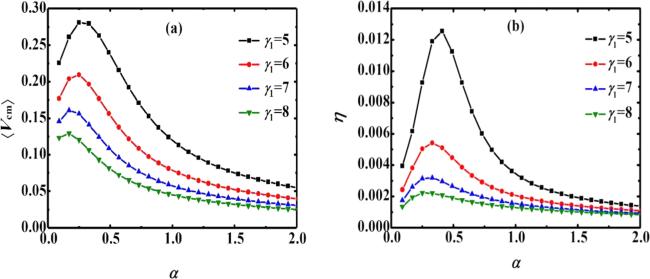

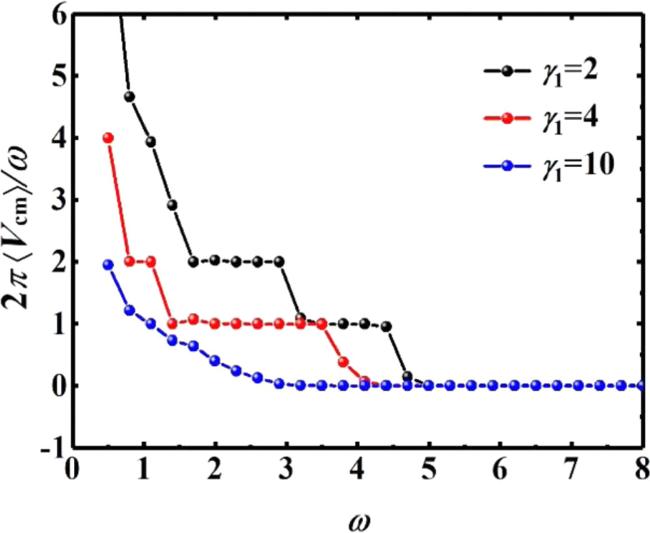

In addition to the driving amplitude $A,$ the frequency of the harmonic force is another important factor to induce the formation of resonant steps. Figure

7 shows the scaled average velocity $2\pi \left\langle {V}_{{\rm{c}}{\rm{m}}}\right\rangle /\omega $ of the dimer as a function of frequency $\omega .$ It can be found that the scaled current could present a series of defined resonance steps. The values of these steps can be given by the ratio $n/m,$ where $n$ and $m$ are integers. The resonance steps in figure

7 can actually be understood as the synchronization regions under the periodic driving effects of harmonic force. The detailed structure of resonance steps in over-damped open-loop ratchets [

50] and under-damped deterministic feedback ratchets [

51] has been reported. It should be noted that the resonance step is, theoretically, a series of defined steps, and its theoretical prediction has been given in [

51]. However, it can be observed only for a part in this inertial frictional ratchet. The property can be well interpreted as that the friction coefficients between the dimer components are different, thus breaking the dynamics of the inertial frictional systems under weak noise intensity (e.g. $D=0.001$) circumstances. Therefore, we can only clearly see part of the steps displayed by the particle current. In addition, as seen in figure

7, the presence of friction has an additional dependency on the resonant steps. This means that the lower the damping force, the more resonance steps. In addition, the decrease in the friction coefficient means that the inertia of the ratchet motion is increased, and the oscillatory fluctuation effect of the velocity caused by the inertial term is strengthened. The oscillation and the mode-locking effect caused by periodic external forces can lead to more resonant steps of directed current. As expected, with the increase in friction, e.g. ${\gamma }_{1}=10,$ the scaled average velocity exhibits a smooth curve and the structure of the resonant steps is broken. This means that some high-order resonance steps will be smoothed out. Nevertheless, the current values scaled in this way are very large under the low-frequency driving conditions. Due to the fact that the average velocity of the dimer is a finite value, the scale current $2\pi \left\langle {V}_{{\rm{c}}{\rm{m}}}\right\rangle /\omega $ increases as the driving frequency decreases. When the frequency of external driving increases, e.g. $\omega \to \infty ,$ it means that the change in external driving is very fast and, at this time, the two coupled particles are generally unable to feel the continuous driving in a short period of time. Therefore, the directional transport of the two coupled particles occurs only under the effects of external loading $f,$ and the corresponding average velocity of the dimer decreases with the increase in the external driving frequency $\omega .$