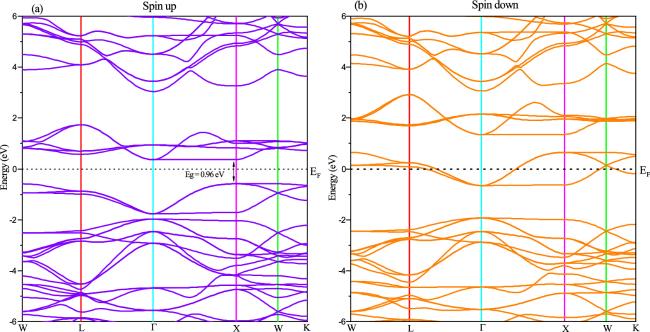

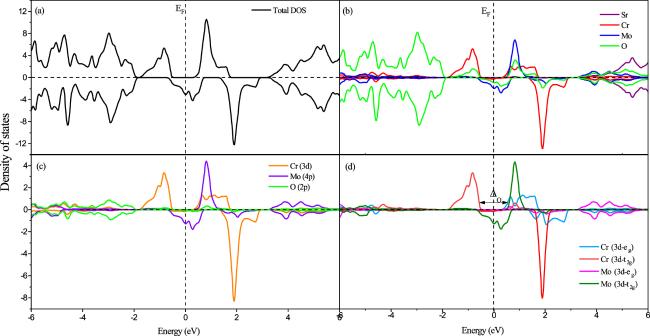

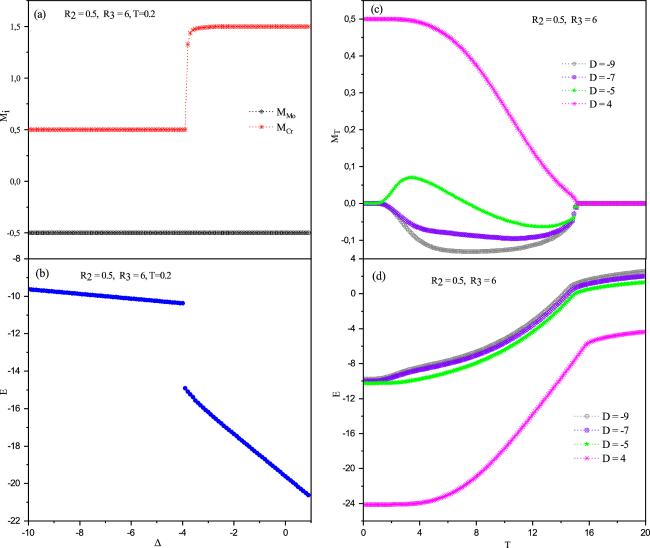

The partial and total electronic densities of states (PDOS and TDOS) in relation to the energy of the SCMO compound are shown in figure

4. Based on the TDOS depicted in figure

4(a), we have determined that the Sr

2CrMoO

6 is a half-metal. This conclusion is drawn from the observation that the spin-down channel displays metallic characteristics due to the band intersection with

EF, whereas the spin-up channel has a band gap of about 0.96 eV at

EF. To comprehend the source of this behavior in the band structure shown in figure

3. We illustrated in figure

4(b) the contribution of each individual atom of this compound. We can see that the spin-down states of Mo and O are clearly visible at

EF. This is accountable for a band gap discovered between the electronic spin-up states of Mo and Cr. Additionally, the oxygen and strontium atoms are not magnetic due to the symmetry of their electronic density of states, while the magnetic properties of SCMO arise from the asymmetry of the density of states of molybdenum and chromium between the density of states for spin-up and spin-down. It is also observed from figure

4(c) that there is a strong hybridization between the 4

d orbitals of molybdenum and 3d orbitals of chromium at

EF for the spin-down state. The presence of a gap between unoccupied Mo (4d) and Cr (3d) states indicates that there is a separation in energy between these orbitals and that they are not fully hybridized. This hybridization and gap can have a significant impact on the magnetic and electronic properties of the material. More specifically, in figure

4(d), the band gap corresponds to an energy gap between the subbands Cr (3d −

eg) and Cr (3d −

t2g) which is primarily due to the octahedral crystal field Δ

o created by the six oxygen atoms that encircle each chromium cation in the crystal structure. Moreover, in figure

4(d), it can be seen that the band Cr (3d −

t2g) contains the orbitals (d

xz, d

yz and d

xy) occupied by low energy electrons, it is evident that they are occupied by spin-up states. On the other side, the orbitals (d

x2−y2 and d

z2) of the band Cr (3d −

eg) that have high energy are unoccupied. The band Mo (4d −

eg) that exists above the Fermi level is unoccupied. Meanwhile the band Mo (4d −

t2g) that exists at

EF contains only one electron with a spin-down state. This fact, which conforms to Hund's rule, clarifies that the molybdenum (Mo

5+) has a spin of $\tfrac{1}{2}$ and element chromium (Cr

3+) has a spin of $\tfrac{3}{2}$.