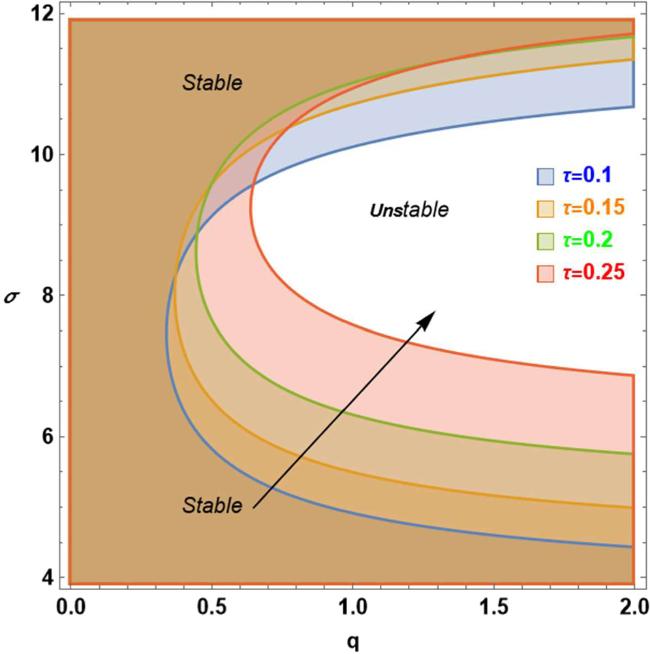

The stability criterion presented in equation (

39) is visualized in figure

2. This criterion is essential as it ensures the validity of the solution derived in equation (

35), contingent upon the damping coefficient

μeq being positive. The plot depicts the (

σ–

q) plane, where the stable and unstable regions are delineated. Within the stable region, it is observed that very small values of

q have negligible effects on the stability behavior. However, as

q increases, an unstable zone emerges within the stable region at a specific value of

q for

τ = 0.1. This unstable zone takes the shape of a parabola, starting at the position of (0.3355, 7.679). The width of this unstable zone increases with increasing

q, illustrating how the amplitude of the stimulated force can lead to instability. Furthermore, the behavior of the unstable region's parabola changes with variations in the delay parameter

τ. Specifically, as

τ increases, the width of the unstable region's parabola decreases, indicating a stabilizing effect. This behavior suggests that raising the delay parameter

τ has a stabilizing influence on the system, leading to a reduction in the potential for instability. Overall, the visualization provided in figure

2 offers insights into how changes in parameters such as q and

τ affect the stability behavior of the system, highlighting the importance of considering these factors in the analysis of resonance phenomena. For the identical system depicted in figure

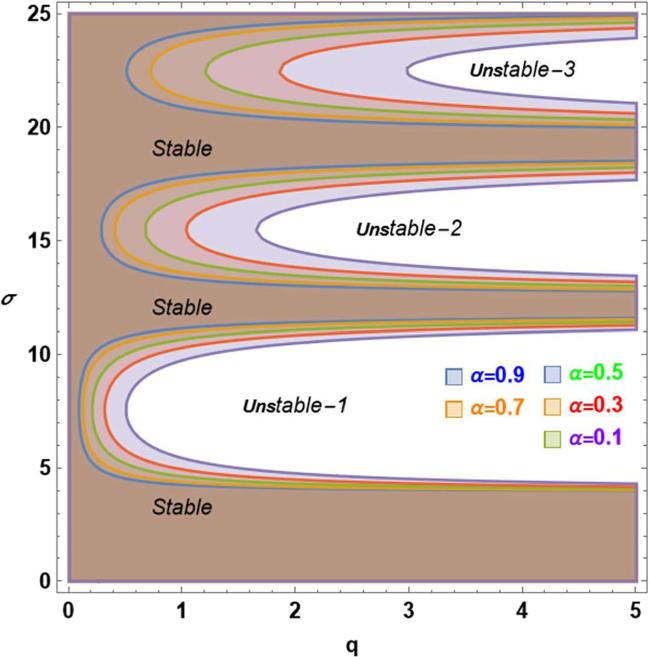

2, the effect of increasing the damping parameter on the stability landscape is investigated and illustrated in figure

3. The variation of the damping coefficient

μ is represented on the graph in figure

3. Upon examination of this graph, it becomes evident that as

μ increases, the diameter of the unstable zone expands, and its position shifts towards lower values along the

q-axis. This behavior implies that an increase in the parameter

μ results in a destabilizing effect on the system. However, it is important to note that this behavior is specifically observed in the context of resonance response. Conversely, in the non-resonance scenario, the stabilizing effect of

μ is well established, indicating that variations in the damping coefficient can have contrasting effects depending on the system's response regime. Overall, the insights provided by figure

3 shed light on the dynamic interplay between the damping coefficient

μ and the stability behavior of the system, particularly in the context of resonance phenomena.