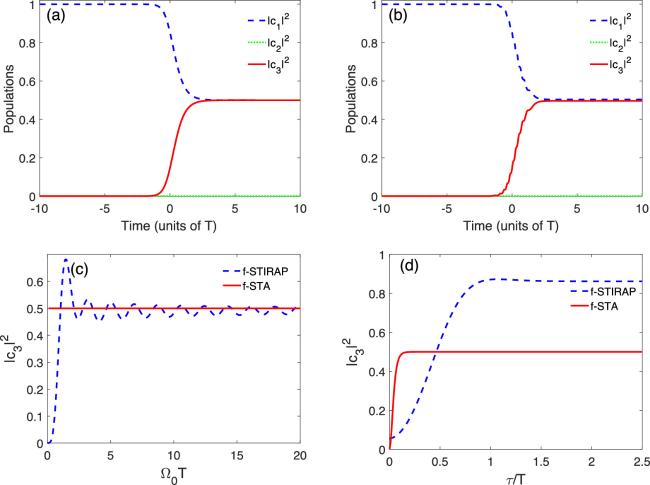

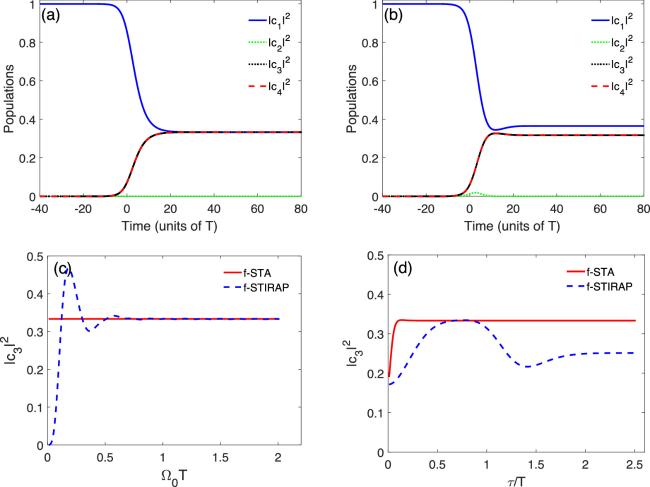

The evolution of the populations for the f-STA and the f-STIRAP via the dark-state passage ∣

λ0(

t)⟩ is demonstrated in figures

2(a) and (b), respectively. The population is assumed to stay on state ∣1⟩ at the initial time, and then 50% of it is transferred to state ∣3⟩ at the final time for the f-STA in figure

2(a). There is no population in the state ∣2⟩ during the whole process. By contrast, the final population on ∣3⟩ does not reach 0.5 for the f-STIRAP in figure

2(b), because there is some population loss due to the nonadiabatic transitions. The f-STA introduces three auxiliary pulses (

9) to eliminate the nonadiabatic transitions, perfectly achieving a coherent superposition state of ∣1⟩ and ∣3⟩ with equal proportion. Figure

2(c) shows the effect of the peak pulse intensity Ω

0 on the population transfer. The final population on ∣3⟩ for the f-STA does not change with Ω

0 and always keeps at 0.5 for the f-STA. The transfer is not sensitive to the change of the pulse intensity. However, the final population on ∣3⟩ for the f-STIRAP increases rapidly with increasing the pulse intensity first, then drops to 0.5 after reaching a peak, and finally oscillates around 0.5 with the characteristic of amplitude attenuation. Obviously, the transfer for the f-STIRAP is affected dramatically by the change in the pulse intensity. Figure

2(d) shows the effect of the time delay

τ on the population transfer. The final population on ∣3⟩ for the f-STA increases rapidly with increasing

τ and reaches 0.5 during a small time delay. For the larger time delay, the population always stays at 0.5. This means the presence of the three auxiliary pulses lessens the requirement that the two driving pulses must overlap. The final population on ∣3⟩ for the f-STIRAP increases with increasing the value of

τ, but the growth of the population is relatively slow, and 50% of the population can be achieved only at

τ ≈ 0.47

T. With increasing the time delay, the population on ∣3⟩ continues to rise and stabilizes after reaching to about 0.86. As the time delay is increased, the overlap between the two driving pulses becomes smaller and smaller. Eventually, the two pulses no longer overlap, leading to a situation where the adiabatic condition is not satisfied. Consequently, the f-STIRAP cannot give reliable results for a larger time delay.