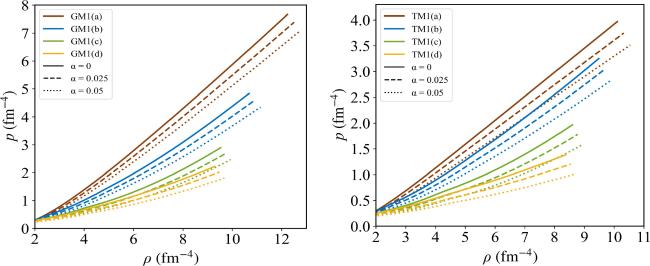

The EOSs for traditional neutron stars and the hyperon stars mixing dark energy are shown in figure

1. With the attendance of dark energy, the EOSs are softened and the degree of softening becomes more pronounced as the fraction of dark energy increases in both the traditional neutron stars and the hyperon stars. After solving equations (

8) and (

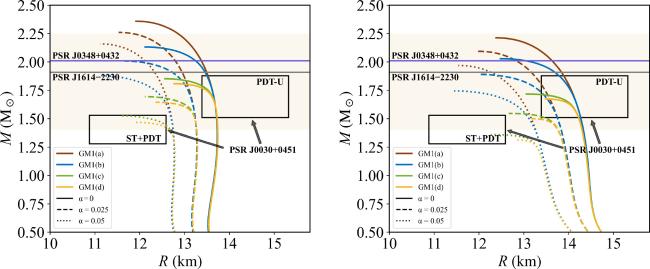

9) for the traditional neutron stars and the hyperon stars with dark energy combining the mass and radius measurements from the astronomical observations of PSRs J1614-2230 (1.908 ± 0.016

M⊙) [

31], J0348+0432 (2.01± 0.04

M⊙) [

32] and J0030+0451 (${1.40}_{-0.12}^{+0.13}$

M⊙, ${11.71}_{-0.83}^{+0.88}$ km for ST+PDT model and ${1.70}_{-0.19}^{+0.18}$

M⊙, ${14.44}_{-1.05}^{+0.88}$ km for PDT-U model) [

33], the mass–radius relationships are shown in figure

2. It can be seen that the radius of a given mass traditional neutron star (or hyperon star) decreases with the increase of the fraction of dark energy, which enhances the compactness of the traditional neutron star (or hyperon star). Furthermore, in a dark energy environment, the mass–radius relationships of the traditional neutron stars and the hyperon stars are consistent with the observed mass and radius ranges of PSRs J1614-2230, J0348+0432 and J0030+0451. Especially, the numerical results for the stars with a mass range of 1.35-1.53

M⊙ can satisfy the mass (${1.40}_{-0.12}^{+0.13}$

M⊙) and radius (${11.71}_{-0.83}^{+0.88}$ km) constraints of PSR J0030+0451 only in the case involving dark energy. The theoretical values of the maximum mass and the corresponding radius, the surface gravitational redshift and the Keplerian frequency of the traditional neutron and the hyperon stars are listed in table

2. As illustrated in figure

2 and table

2, the emergence of dark energy causes the maximum mass of the traditional neutron star in the GM1 (TM1) parameter set to decrease from 2.360

M⊙ (2.213

M⊙) to 2.159

M⊙ (1.969

M⊙), and the maximum mass of the hyperon star decrease from 2.132

M⊙ (2.029

M⊙) to 1.525

M⊙ (1.361

M⊙).