1. Introduction

2. Modeling and simulation

2.1. Assumption

| (1)the materials are all linear elastic and isotropic, | |

| (2)the film and the substrate are perfectly bonded at the boundary, | |

| (3)the structure is in a stable temperature field environment, | |

| (4)no initial residual stress, | |

| (5)the temperature dependence of CTE is negligible. |

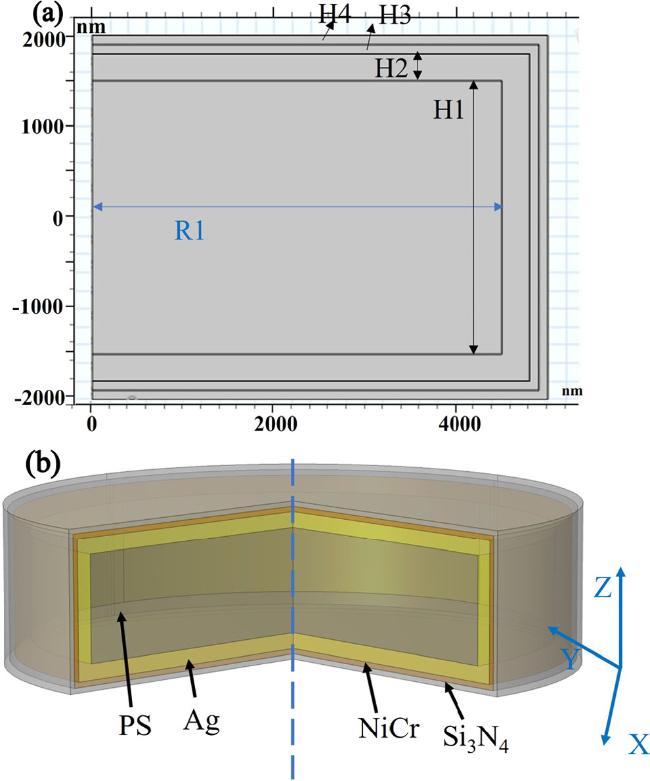

2.2. Establishment of a structural model

Figure 1. (a) 2D axisymmetric diagram of the structure; (b) 3D view of the structure. |

Table 1. Mechanical and thermal parameters of each material. |

| Materials | Young's modulus (Pa) | Poisson's ratio | Density (kg m−3) | Thermal expansion coefficient (1/K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | 3.3 × 109 | 0.32 | 1120 | 8.0 × 10−5 |

| Ag | 7.3 × 1010 | 0.38 | 10490 | 1.9 × 10−5 |

| NiCr | 2.0 × 1011 | 0.29 | 8200 | 1.3 × 10−4 |

| Si3N4 | 3.7 × 1011 | 0.25 | 3100 | 3.0 × 10−6 |

Table 2. List of symbols. |

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| α | Coefficient of thermal expansion | 1/K |

| αf | Coefficient of thermal expansion of film | Pa |

| αs | Coefficient of thermal expansion of substrate | Pa |

| γ | Shear strain on the plane | — |

| ϵ | Stress on the plane | Pa |

| σ | Strain on the plane | — |

| &ugr; | Poisson's ratio | — |

| &ugr;f | Poisson's ratio of film | — |

| &ugr;s | Poisson's ratio of substrate | — |

| τ | Shear stress on the plane | Pa |

| E | Young's modulus | Pa |

| Ef | Young's modulus of film | Pa |

| Es | Young's modulus of substrate | Pa |

| Fx | Components of the unit volume force on the x axis | N |

| Fy | Components of the unit volume force on the y axis | N |

| Fz | Components of the unit volume force on the z axis | N |

| G | Shear modulus | — |

| h | Thickness of film | nm |

| H | Thickness of substrate | nm |

| T | Temperature | K |

| Tr | Room temperature | K |

| Td | Ambient temperature | K |

3. Thermal stress analysis in multilayers

3.1. Mathematical model of thermodynamic analysis

3.2. Thermal stress analysis in multilayer structure

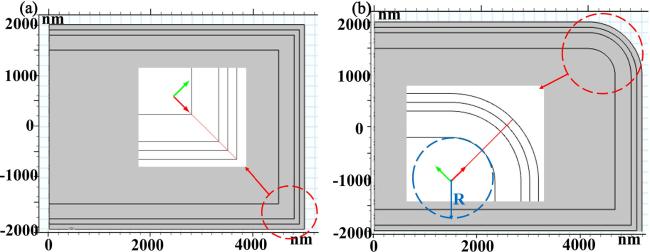

Figure 2. (a) Selection method for 2D cutting lines with right angles; (b) selection method for 2D cutting lines with rounded corners. |

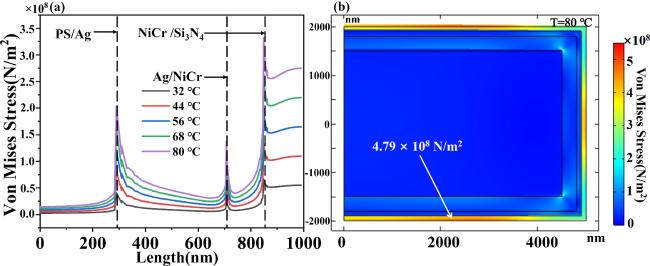

Figure 3. (a) Thermal stress value from 32 °C to 80 °C obtained at the 2D cut line; (b) thermal stress distribution at the structural temperature of 80 °C. |

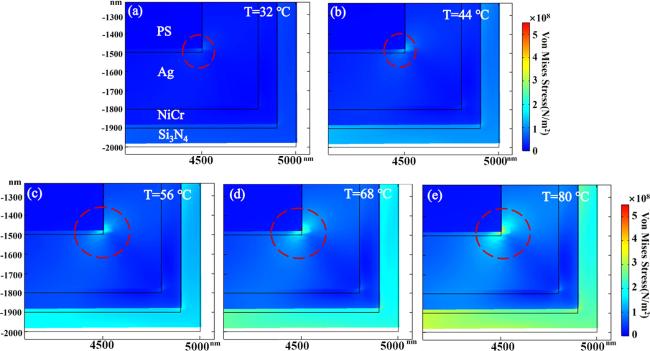

Figure 4. (a)–(e) Thermal stress between and in the film when the structure temperature increases from 32 °C to 80 °C. |

4. Reducing the thermal stress mismatch in multilayers

4.1. The influence of chamfering on the thermal stress concentration point

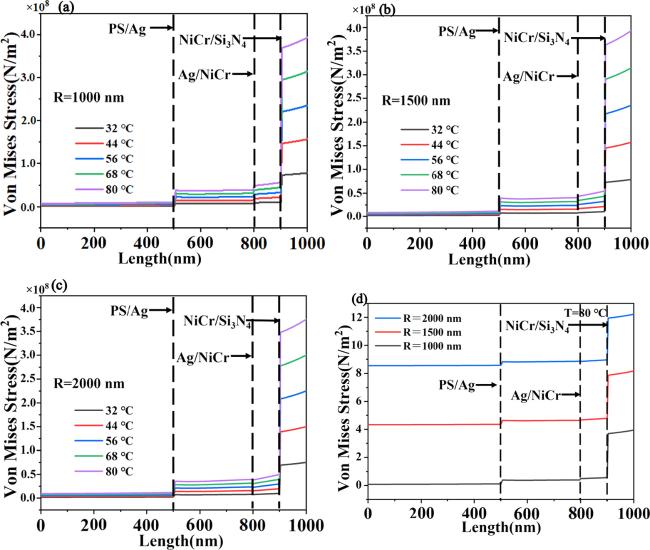

Figure 5. (a)–(c) When the chamfer radius is 1000, 1500 and 2000 nm, respectively, the thermal stress value with the temperature rises from 32 °C to 80 °C. (d) When the temperature is 80 °C, the thermal stress at three chamfer radii are compared. |

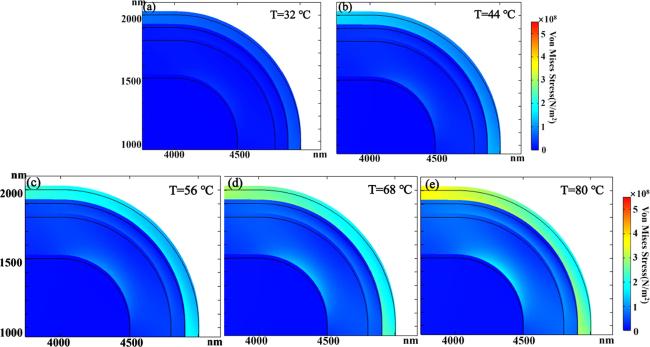

Figure 6. When temperature is at 80 °C, the thermal stress diagrams of three different chamfer radii. |

Table 3. When the temperature is 80 °C, the thermal stress difference between the film layers under three chamfer radii. |

| Chamfer radius | Thermal stress difference of PS-Ag (N m−2) | Thermal stress difference of Ag-NiCr (N m−2) | Thermal stress difference of NiCr-Si3N4 (N m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 nm | 2.73 × 107 | 0.99 × 107 | 31.48 × 107 |

| 1500 nm | 2.73 × 107 | 0.32 × 107 | 30.87 × 107 |

| 2000 nm | 2.36 × 107 | -0.07 × 107 | 29.82 × 107 |

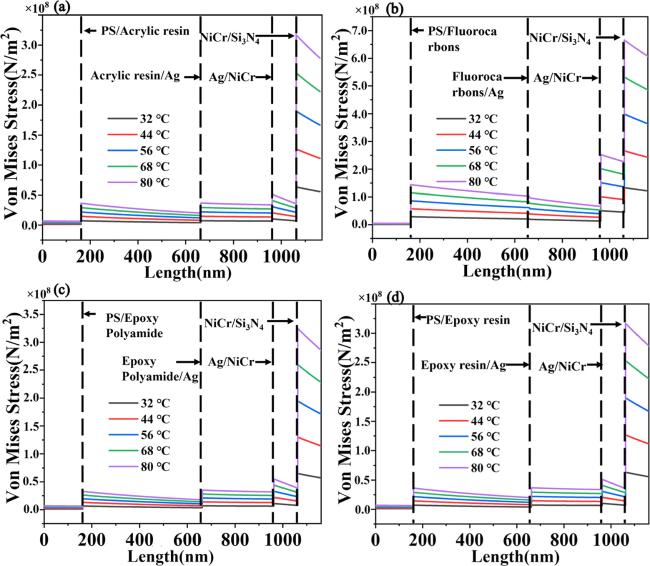

4.2. The effect of increasing the intermediate layer on the sudden change of thermal stress

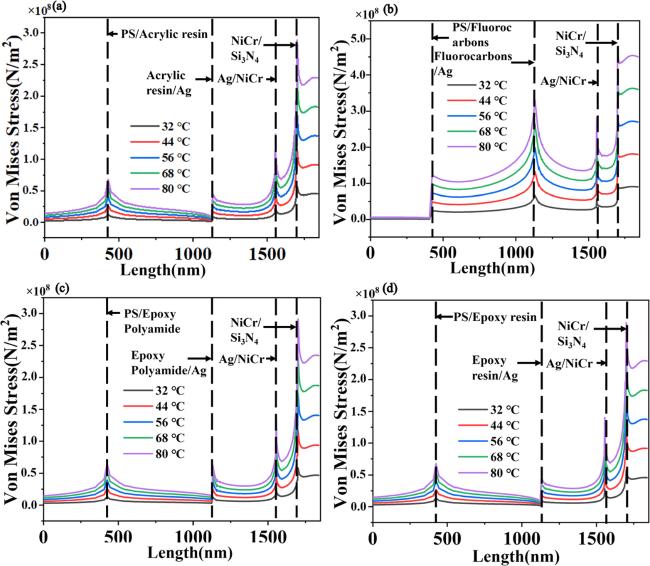

Figure 7. Different intermediate layer added between the PS and Ag layers without chamfering. Added intermediate layers are (a) acrylic resin; (b) fluorocarbons; (c) epoxy polyamide; (d) epoxy resin. |

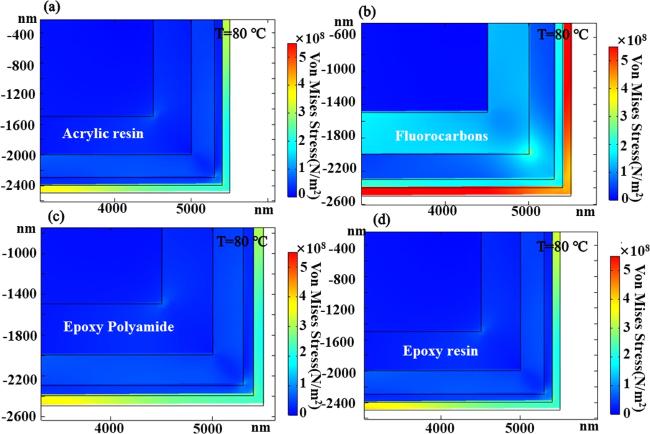

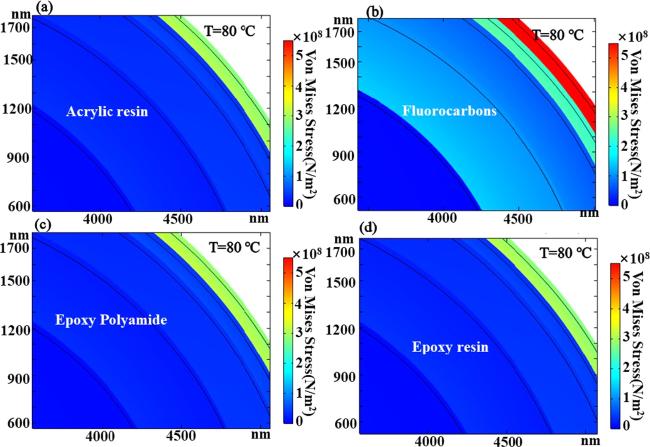

Figure 8. Thermal stress diagrams at 80 °C with different intermediate layers. |

Table 4. Mechanical and thermal parameters of different intermediate layers. |

| Materials | Young's modulus (Pa) | Poisson's specific | Density (kg m−3) | Thermal expansion coefficient (1/K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylic resin | 1.00 × 1010 | 0.17 | 1090 | 1.00 × 10−6 |

| Fluorocarbons | 6.60 × 1010 | 0.17 | 1280 | 5.76 × 10−5 |

| Epoxy polyamide | 1.00 × 1010 | 0.17 | 1300 | 6.00 × 10−6 |

| Epoxy resin | 1.00 × 1010 | 0.193 | 1300 | 1.00 × 10−6 |

Figure 9. (a)–(d) After adding different intermediate layers, the thermal stress changes with the increase in temperature. |

Figure 10. Intermediate layer added while the chamfer radius is 2000 nm. |

Table 5. The thermal stress difference between the film layers when different intermediate layers are added, respectively. |

| Intermediate layer | Thermal stress difference of PS intermediate layer (N m−2) | Thermal stress difference of intermediate layer Ag (N m−2) | Thermal stress difference of Ag NiCr (N m−2) | Thermal stress difference of NiCr Si3N4 (N m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylic resin | 3.02 × 107 | 1.68 × 107 | 1.74 × 107 | 28.15 × 107 |

| Fluorocarbons | 9.71 × 107 | −0.63 × 107 | 18.64 × 107 | 43.93 × 107 |

| Epoxy polyamide | 2.65 × 107 | 1.75 × 107 | 2.32 × 107 | 28.61 × 107 |

| Epoxy resin | 3.00 × 107 | 1.69 × 107 | 1.75 × 107 | 28.15 × 107 |