1. Introduction

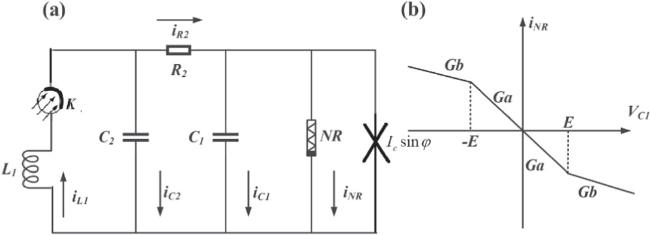

2. Model and Scheme

Figure 1. (a) Double membrane, magnetic sensitive, light sensitive neuron model constructed by Chua’s circuit. (b) I-V characteristic curve of the Chua’s diode, it’s a nonlinear resistance (NR). |

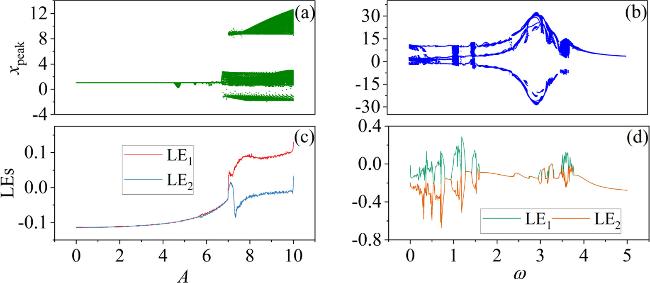

3. Calculation results and analysis

Figure 2. Bifurcation and LEs’diagrams of the uK’s A and ω in the neuron model. The parameters corresponding to the diagrams: (a), (c) ω = 0.01; (b), (d) A = 8.8. Other parameters: $\alpha $ = 10, $\beta $ = 9, Ic = 8, m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, d = 1. The initial values: (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |

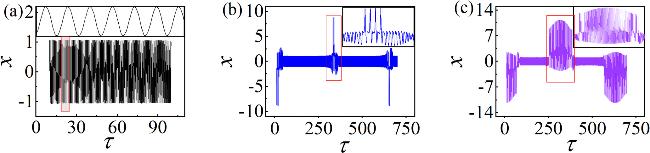

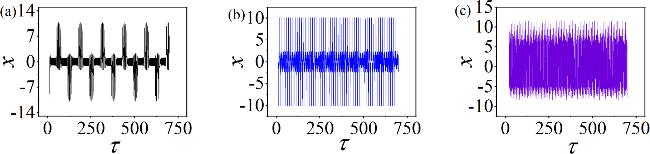

Figure 3. Time sequences of membrane potentials under varying A (the small image is a partial enlargement of the area with red borders). Corresponding A: (a) A = 5; (b) A = 7; (c) A = 9. Other parameters: $\alpha $ = 10, $\beta $ = 9, Ic = 8, m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, ω = 0.01, d = 1. The initial values: (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |

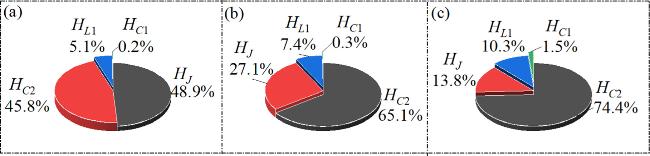

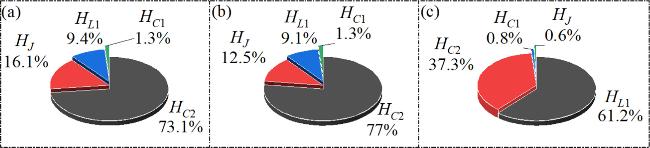

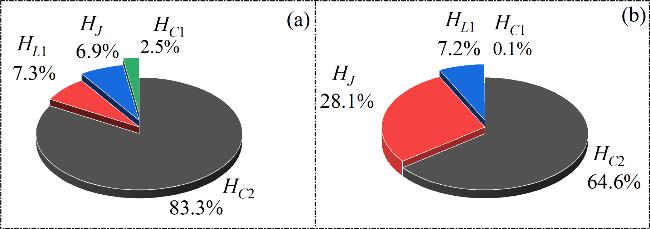

Figure 4. The proportion of field energy in each component to the Hamiltonian energy under different light illumination conditions, (a) A = 5, (b) A = 7, (c) A = 9; Other parameters: $\alpha $ = 10, $\beta $ = 9, Ic = 8, m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, ω = 0.01, d = 1. The initial values are set to: (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |

Figure 5. Time sequences of membrane potentials under different ω, with: (a) ω = 0.05; (b) ω = 0.5; (c) ω = 3.5. Other parameters: $\alpha $ = 10, $\beta $ = 9, Ic = 8, m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, A = 8.8, d = 1. The initial values are set to: (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |

Figure 6. Proportions of energy in various components by different ω. with(a) ω = 0.05; (b) ω = 0.5; (c) ω = 3.5. Other parameters: $\alpha $ = 10, $\beta $ = 9, Ic = 8, m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, A = 8.8, d = 1. The initial values: (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |

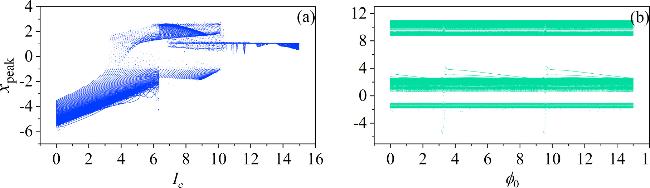

Figure 7. Fixed external illumination, the bifurcation of Josephson current parameter Ic and the initial value of ${\phi }_{0}$. The parameters corresponding to: (a) ${\phi }_{0}$ = 2; (b) Ic = 8. Other parameters: a = 10, b = 9, m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, $\omega $ = 0.01, A = 8.8, d = 1. The initial values (0.1, 0.1, 0.1). |

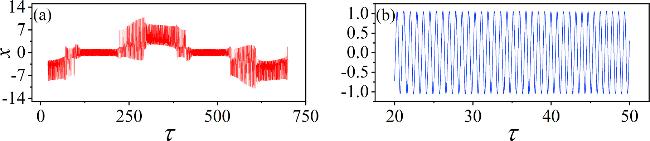

Figure 8. Time series of membrane potential for different Josephson junction current parameters Ic. (a) Ic = 6; (b) Ic = 11. Other parameters: α = 10, β = 9, m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, $\omega $ = 0.01, A = 8.8, d = 1. The initial values (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |

Figure 9. The energy percentage of the individual components under different Ic. (a) Ic = 6; (b) Ic = 11. Other parameters: α = 10, β = 9, m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, $\omega $ = 0.01, A = 8.8, d = 1. The initial values: (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |

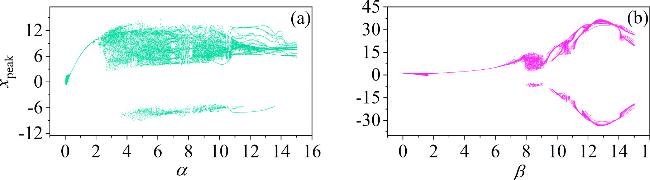

Figure 10. Bifurcation diagram of the neuron circuit corresponding to variations in α and β. The parameters are set as follows: (a) $\beta $ = 9; (b) α = 10. The other parameter: m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, $\omega $ = 3.5, d = 1, A = 8.8, and Ic = 8. The initial conditions (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |

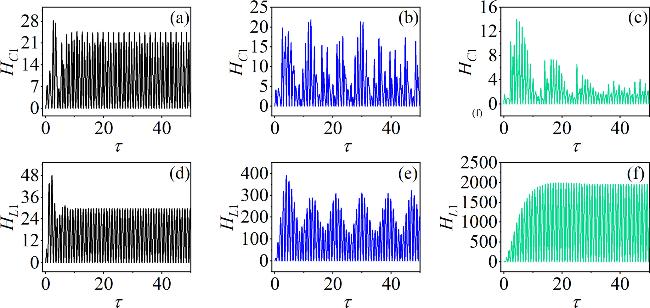

Figure 11. Time evolution of the electric field energy stored in C1 and the magnetic field energy stored in L1 corresponding to different values as: (a) α = 2, (b) α = 4, (c) α = 11; (d) β = 4, (e) β = 8.5, (f) β = 13.5. For (a)–(c) β = 9; for (d)–(f) α = 10. Other parameters: m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, $\omega $ = 3.5, A = 8.8, and Ic = 8, d = 1. The initial conditions are set to (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |

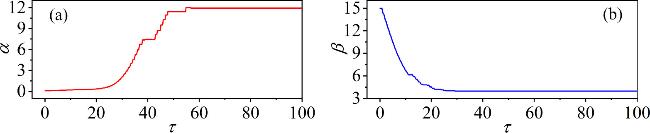

Figure 12. Targeted modulation of the field energy in the capacitor and inductor corresponding to their time-varying parameters $\alpha (\tau )$ and $\beta (\tau )$. The parameters: (a)${\alpha }_{0}$ = 0.01, ${\sigma }_{1}$ = 0.3, ${\varepsilon }_{1}$ = 4.5; (b)${\beta }_{0}$ = 15, ${\sigma }_{2}$ = −0.1, ${\varepsilon }_{2}$ = 30. Other parameters: m0 = −1, m1 = 0.9, $\omega $ = 3.5, A = 8.8, Ic = 8, d = 1. The initial conditions: (0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 2). |