1. Introduction

2. Model

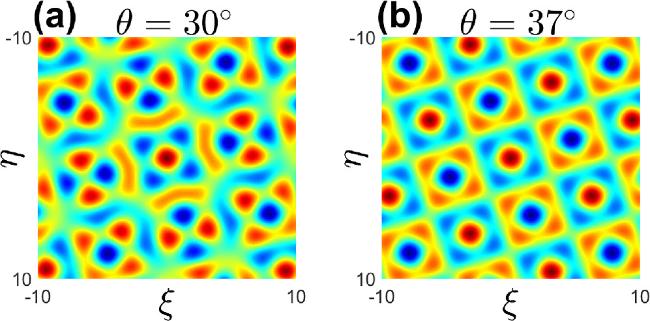

Figure 1. (a−b) The square Moiré lattice is formed by two sub-lattices with equal lattice depths (p1 = p2 = 1), each rotated by angles θ = 30° and θ = 37° (θ = arctan(3/4)), respectively, to create an external potential field. |

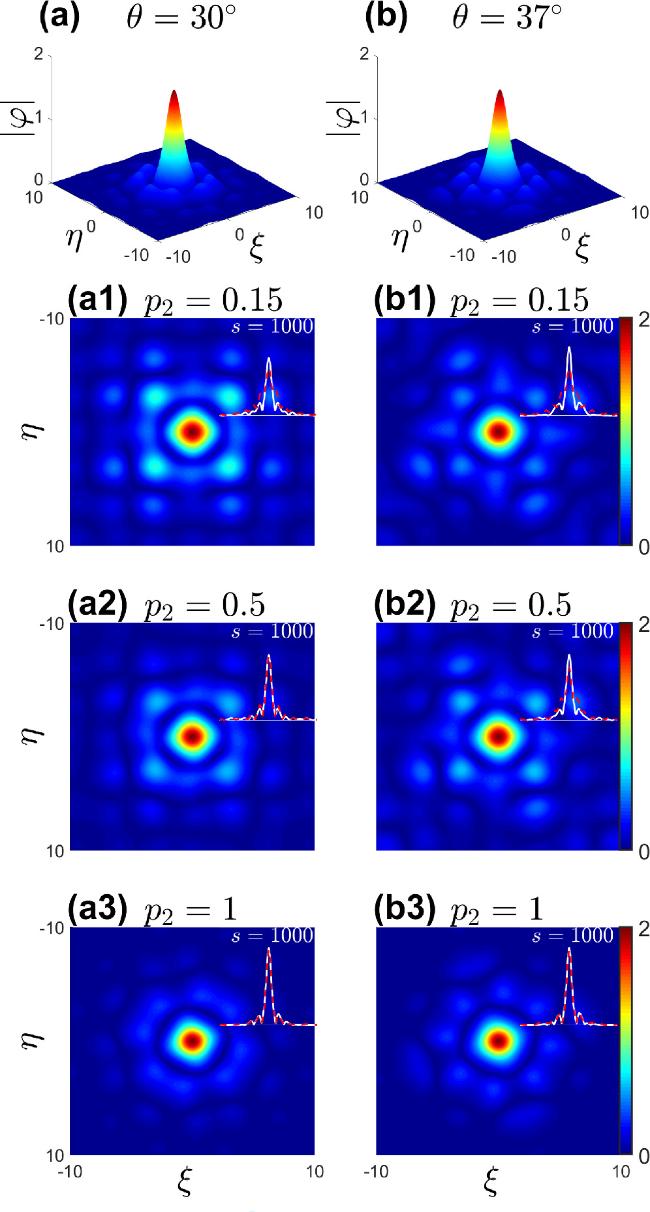

3. Soliton excited at the center of the potential field

Figure 2. (a-b) When p1 = p2 = 1, there are stable soliton solutions under the Moiré lattice external potential fields at rotation angles θ = 30° and θ = 37°. (a1-a3) show top-down views of soliton solutions were depicted at the same angle θ = 30°, with respective values of p2 = 0.15 (a1), p2 = 0.5 (a2), and p2 = 1 (a3). Under this parameter setting, the insets depict a comparison of soliton profiles before and after soliton evolution (where η = 0). The solid white line represents the soliton profile before evolution, while the red dotted line represents the soliton profile after evolution, with an evolution duration of s = 1000. (b1-b3) follow the same format. |

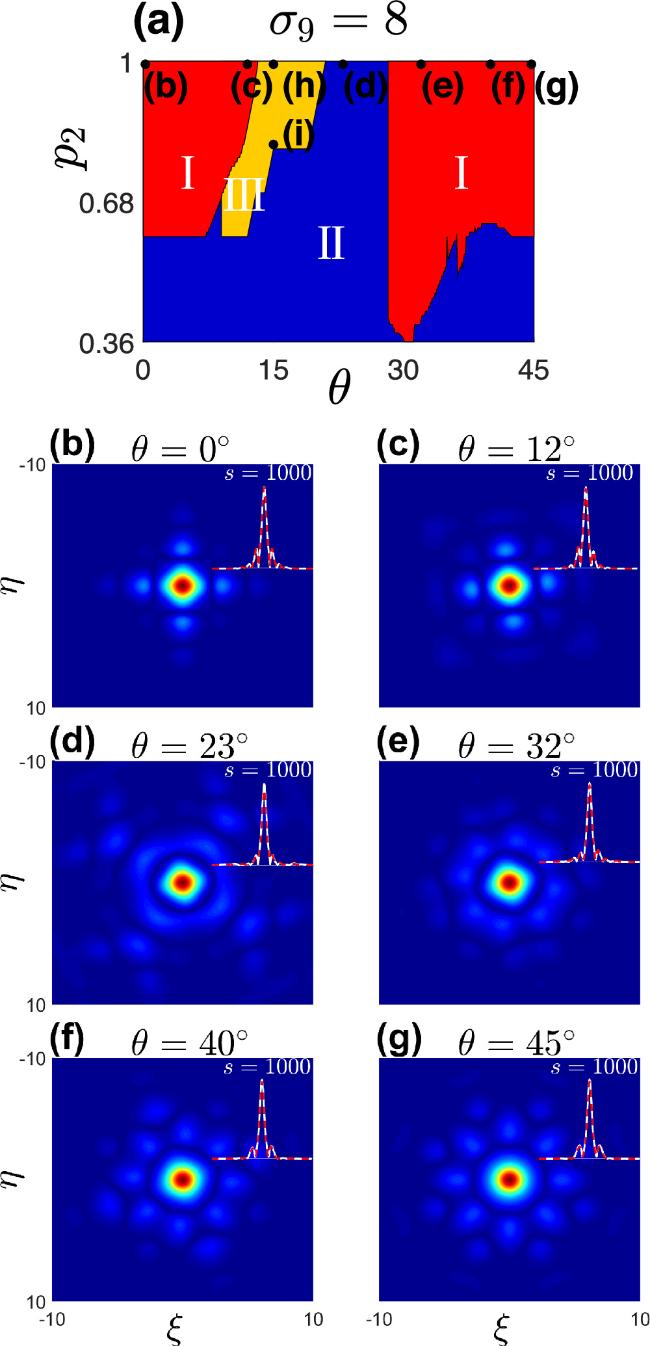

Figure 3. (a) The various solitons exist different regions under varying rotation angles θ and secondary sub-lattice depths p2: red Region I, blue Region II and orange Region III. (b-g) When p2 = 1, the top-view of the soliton at different rotation angles is shown, and the insets depicts a comparison of soliton profiles before and after soliton evolution (where η = 0). These solutions correspond to points (b-g) in diagrams (a). |

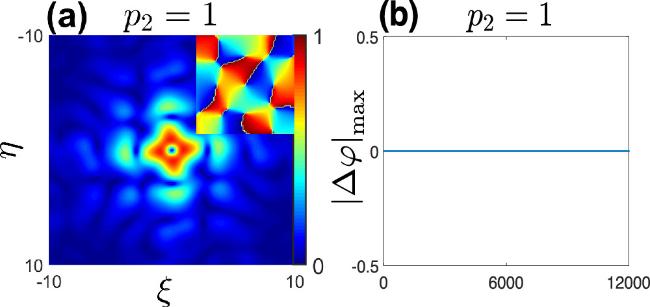

Figure 4. (a) For θ = 15° and p2 = 1, a top-down view of the square bright vortex soliton solution is presented, accompanied by an inset that illustrates the phase profiles of the square bright vortex soliton solution. (b) shows the changes in ${\left|{\rm{\Delta }}\varphi \right|}_{{\rm{\max }}}$ of the square bright vortex soliton solution during its evolution at s = 12000. This bright vortex result corresponds to the middle (h) point in figure 3(a). |

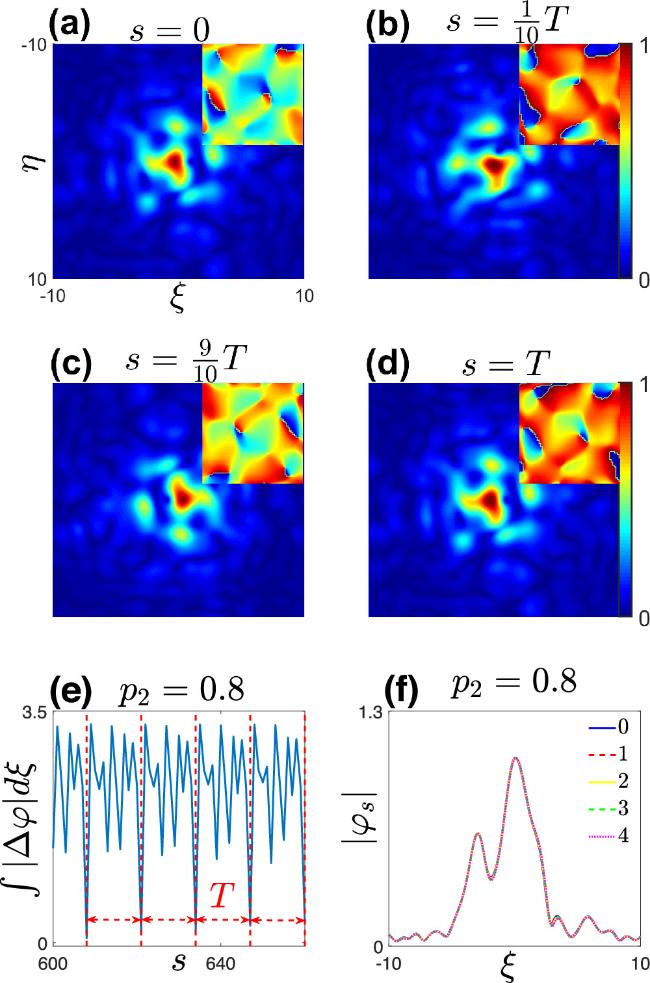

Figure 5. (a)–(d) For θ = 15° and p2 = 0.8, a top-down view of the square bright vortex soliton solution is presented and show the morphology of the bright vortex at different times within one period. These insets illustrate the phase profiles of the square bright vortex soliton. (e) shows the changes in $\int \left|{\rm{\Delta }}\varphi \right|d\xi $ of the square bright vortex soliton solution during its evolution at s = 12000. (f) shows the bright vortex profile along the ξ direction at a selected time s = 0 (the blue solid line, legend 0), compared with the soliton solution profiles after one (the red dotted line, legend 1), two (the yellow solid line, legend 2), three (the green dotted line, legend 3), and four (the purple dot line, legend 4) periods. The period is T = 13. This bright vortex result corresponds to the middle (i) point in figure 3(a). |

4. Soliton excited at the off-center of the potential field

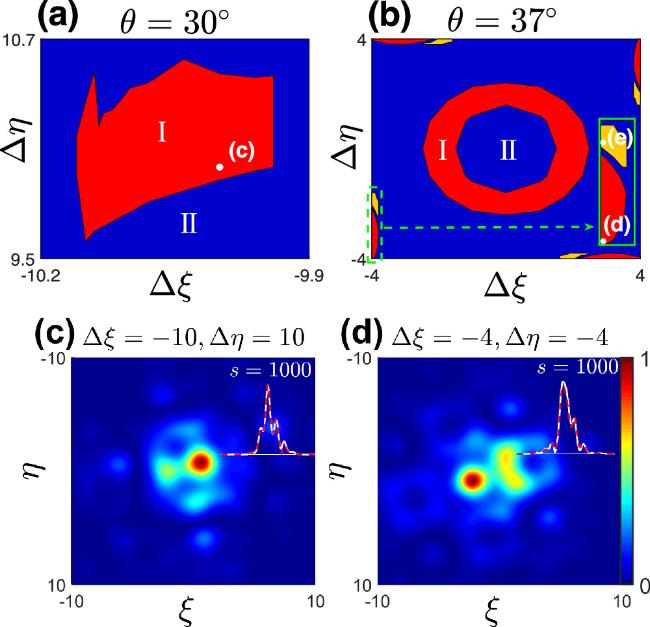

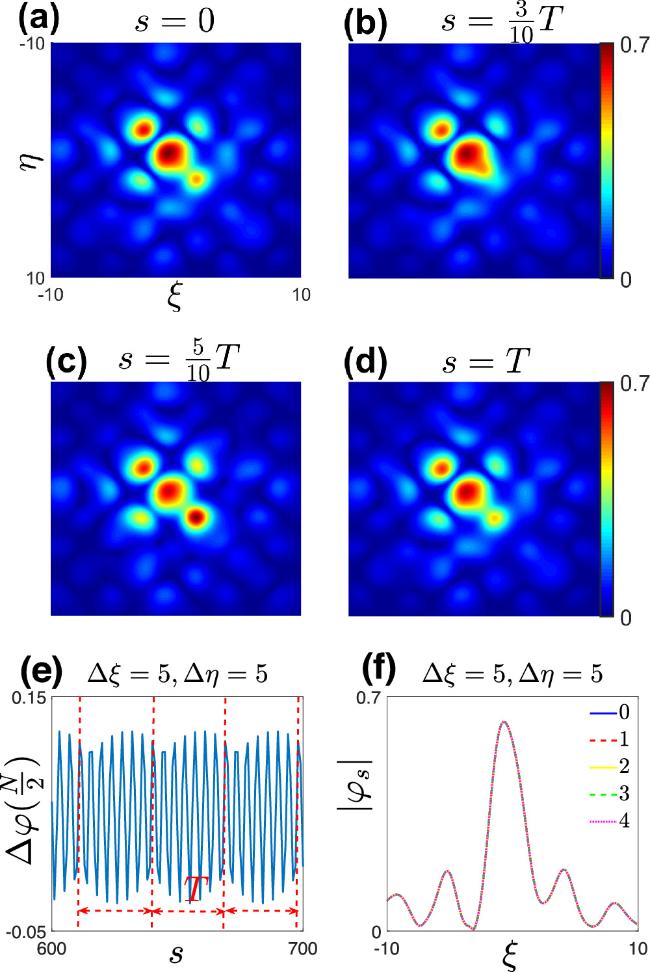

Figure 6. (a) When θ = 30°, in the vicinity of the region where the displacement from the external potential center is Δξ = − 10 and Δη = 10, statically stable solitons exist in the red region I. (b) When θ = 37°, in the vicinity of the region where the displacement from the external potential center is ${\rm{\Delta }}\xi \in \left[-4:\,4\right]$ and ${\rm{\Delta }}\eta \in \left[-4:\,4\right]$, statically stable solitons exist in the red Region I and periodic dynamic solitons exist in the orange Region. The inset shows an enlarged view of the area enclosed by the green dotted line. (c) When Δξ − 10 and Δη = 10, the statically stable soliton is shown, and the inset depicts a comparison of soliton profiles before and after soliton evolution. The solution correspond to points (c) in diagrams (a). (d) When Δξ = − 4 and Δη = − 4, the statically stable soliton is shown, and the inset depicts a comparison of soliton profiles before and after soliton evolution. The solution correspond to points (d) in diagrams (b). |

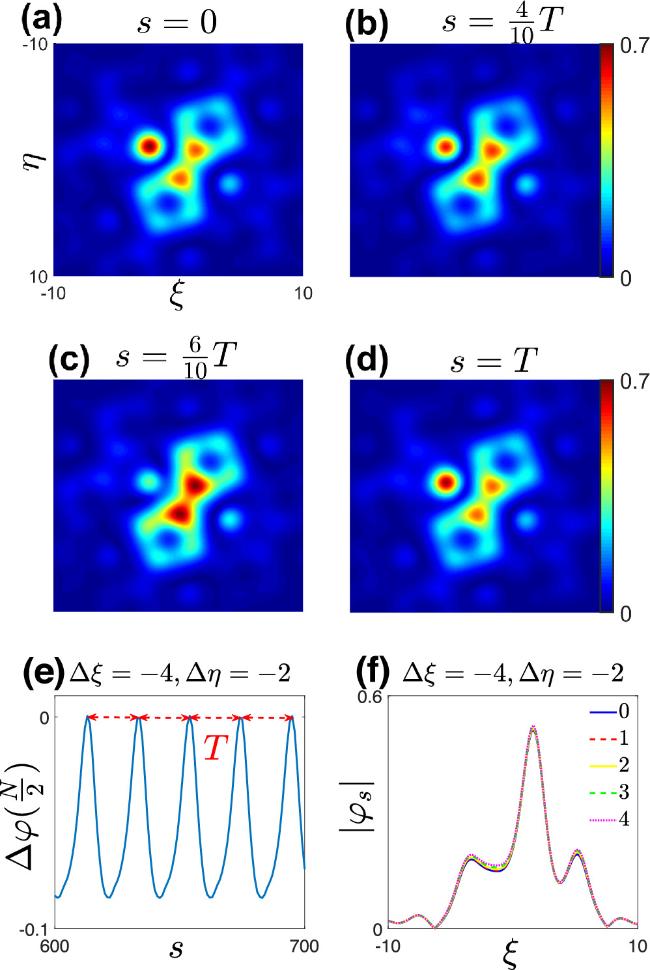

Figure 7. (a)–(d) When the rotation angle θ = 37°, a three-peak periodic dynamic soliton at the displacement from the external potential center Δξ= -4 and Δη= -2. And they show the morphology of the bright soliton at different times within one period. (e) shows the changes in ${\rm{\Delta }}\varphi (\frac{N}{2})$ of the soliton during its evolution at s = 12000. (f) shows the soliton profile along the ξ direction at a time s = 0, compared with the soliton profiles after one, two, three, and four periods. And T = 20. This periodic dynamic soliton corresponds to the (e) point in figure 6(b). |

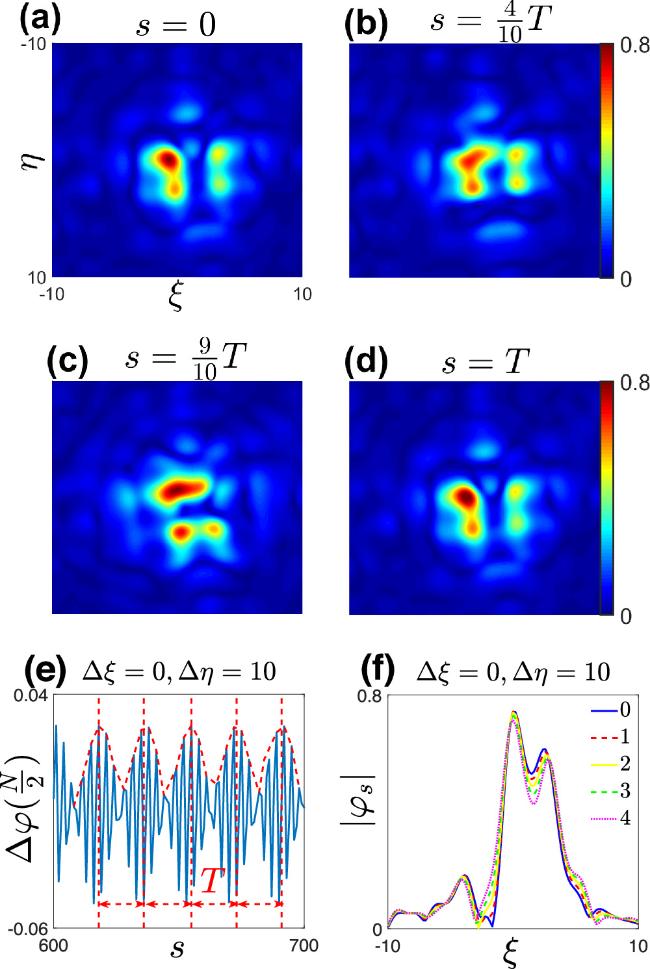

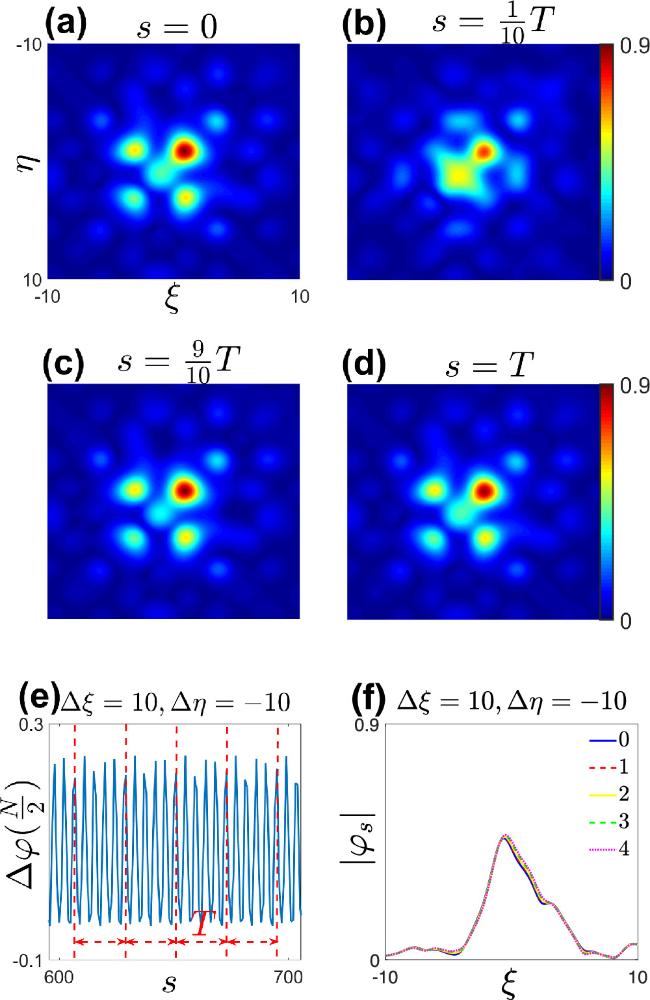

Figure 8. (a)–(d) When the rotation angle θ = 15°, a four-peak periodic dynamic soliton at the displacement from the external potential center Δξ = 0 and Δη = 10. And they show the morphology of the bright soliton at different times within one period. (e) shows the changes in ${\rm{\Delta }}\varphi \left(\frac{N}{2}\right)$ of the soliton during its evolution at s = 12000. (f) shows the soliton profile along the ξ direction at a time s = 0, compared with the soliton solution profiles after one, two, three, and four periods. And T = 18. |

Figure 9. (a)–(d) When the rotation angle θ = 45°, a five-peak periodic dynamic soliton at the displacement from the external potential center Δξ = 5 and Δη = 5. And they show the morphology of the bright soliton at different times within one period. (e) shows the changes in ${\rm{\Delta }}\varphi \left(\frac{N}{2}\right)$ of the soliton during its evolution at s = 12000. (f) shows the soliton profile along the ξ direction at a time s = 0, compared with the soliton solution profiles after one, two, three, and four periods. And T = 29. |

Figure 10. (a)–(d) When the rotation angle θ = 45°, a five-peak periodic dynamic soliton at the displacement from the external potential center Δξ = 10 and Δη = −10. And they show the morphology of the bright soliton at different times within one period. (e) shows the changes in ${\rm{\Delta }}\varphi \left(\frac{N}{2}\right)$ of the soliton during its evolution at s = 12000. (f) shows the soliton profile along the ξ direction at a time s = 0, compared with the soliton solution profiles after one, two, three, and four periods. And T = 22. |

5. Summary

Appendix A. Relevant definitions of stable soliton

Appendix B. The impact of Gaussian amplitude σ9

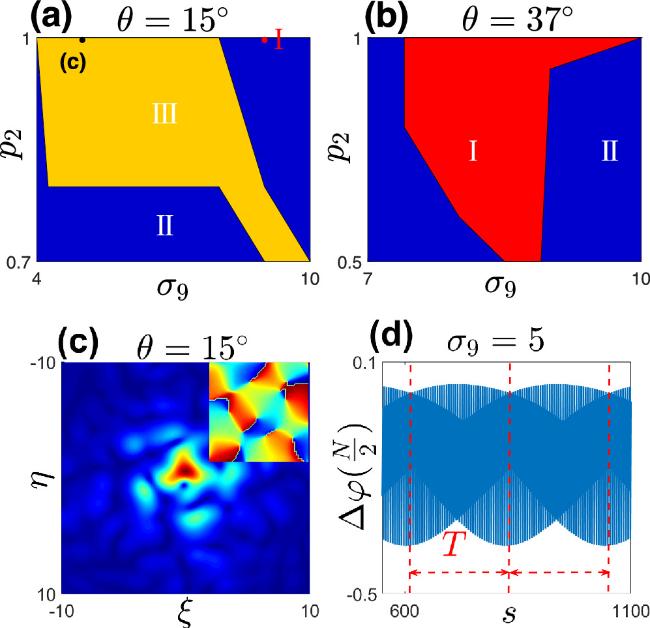

Figure 11. (a–b) When θ = 15° and θ = 37°, the various solitons exist different regions under varying secondary sub-lattice depths p2 and Gaussian amplitude σ9. (c) For θ = 15° p2 = 0.8 and σ9 = 5, a top-down view of the square periodic dynamic bright vortex soliton is presented. The inset shows the phase profiles of the bright vortex. The solution correspond to points (c) in diagrams (a). (d) shows the changes in ${\rm{\Delta }}\varphi (\frac{N}{2})$ of the periodic dynamic soliton during its evolution at s = 12000. And T = 223. |

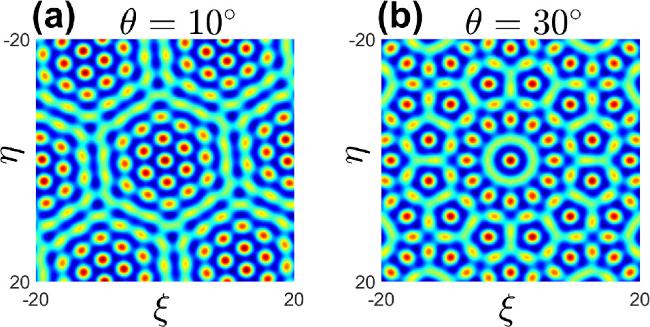

Appendix C. The impact of the hexagonal Moiré lattice

Figure 12. (a–b) The hexagonal Moiré lattice is formed by two sub-lattices with equal lattice depths (p1 = p2 = 1), each rotated by angles θ = 10° and θ = 30°, respectively, to create an external potential field. |

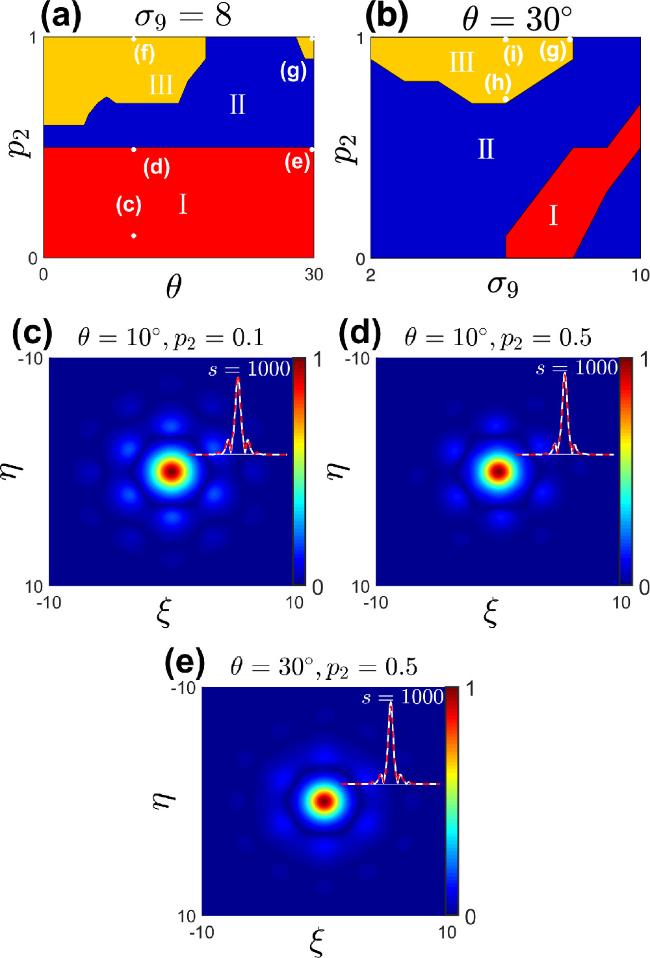

Figure 13. (a-b) When σ9 = 8 and θ = 30°, the various solitons exist different regions. (c-d) When θ = 10° and σ9 = 8, the top-view of the soliton at different p2 is shown, and the insets depicts a comparison of soliton profiles before and after soliton evolution. These solutions correspond to points (c) and (d) in diagram (a). (e)When θ = 30°, σ9 = 8 and p2 = 0.5, the top-view of the soliton is shown, and the insets depicts a comparison of soliton profiles before and after soliton evolution. The solution correspond to points (e) in diagram (a). |

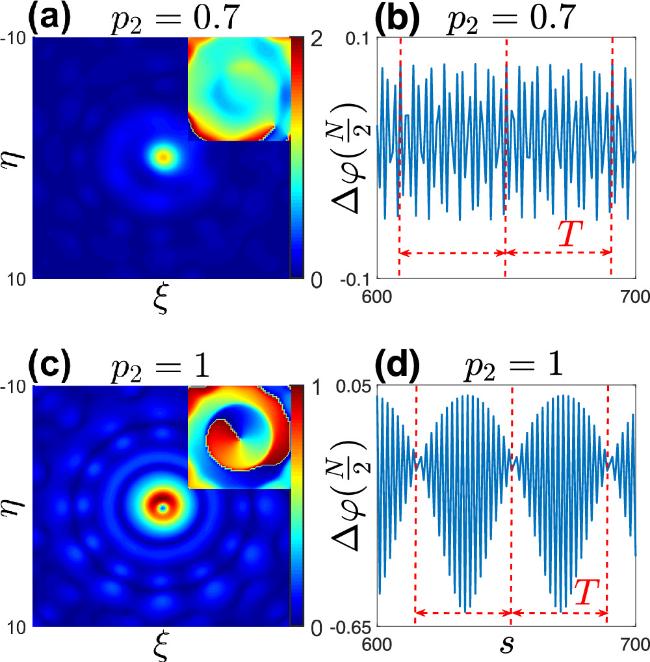

Figure 14. (a), (c) show two periodic dynamic bright vortices, while θ = 30° and σ9 = 6. The insets show the phase profiles of the bright vortices. These solutions correspond to points (h) and (i) in figure 13(b). (b) shows the changes in ${\rm{\Delta }}\varphi (\frac{N}{2})$ of the periodic dynamic vortex (a) during its evolution at s = 12000. And T = 41. (d) shows the changes in ${\rm{\Delta }}\varphi (\frac{N}{2})$ of the periodic dynamic vortex (c) during its evolution at s = 12000. And T = 37. |

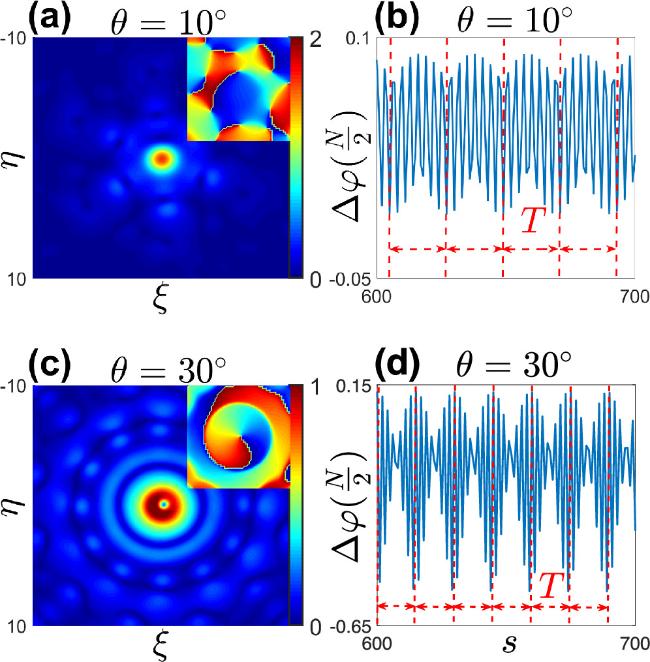

Figure 15. (a), (c) show two periodic dynamic bright vortices, while p2 = 1 and σ9 = 8. The insets show the phase profiles of the bright vortices. These solutions correspond to points (f) and (g) in figure 13(a). (c) also correspond to points (g) in figure 13(b). (b) shows the changes in ${\rm{\Delta }}\varphi (\frac{N}{2})$ of the periodic dynamic vortex (a) during its evolution at s = 12000. And T = 22. (d) shows the changes in ${\rm{\Delta }}\varphi (\frac{N}{2})$ of the periodic dynamic vortex (c) during its evolution at s = 12000. And T = 15. |