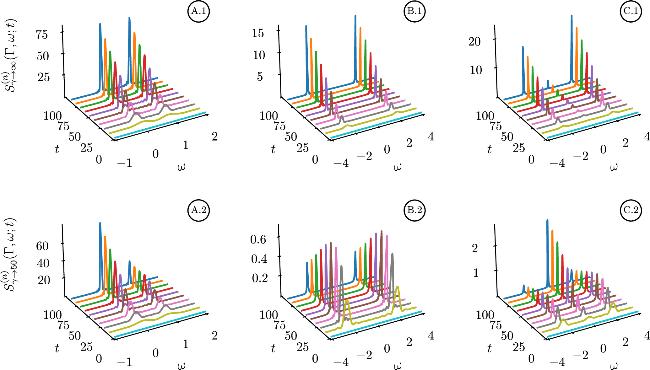

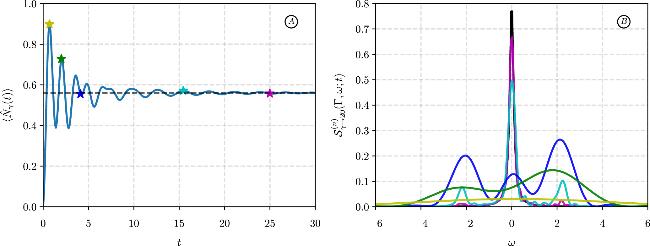

At first, the intention to include the quadratic term responds to the fact that the preservation of harmonic behavior when just linear coupling is considered, has an upper bound; thus, higher regimes preserving the semi-positiveness of the eigenvalues, needs the quadratic and upper orders in the interaction. On the other hand, including dephasing over dissipation is intended to represent, for example, results where gravitational decoherence can be mimicked with pure dephasing optomechanical systems [

22–

24], this leads to thinking that exploring such optomechanical analogs may shed light on gravitationally induced dephasing dynamics of macroscopic matter-field superposition states, as it was stated in [

25]. Moreover, other kinds of related systems, like many-bodies, and quantum dots, may exhibit dephasing [

26–

28], or in the quantum sensing realm, where testing on the gravity acceleration can be estimated through the phase readout of the field-resonator coupling phase [

29]. Thus, capturing information about the dephasing mechanism and its influence on the quantum mechanical systems appears to be natural. Considering the dephasing as the mechanism where energy-preserving damping occurs, it can be thought as a scattering process with interference terms proportional to the number operator of the Hamiltonian, where no energy is lost or gained, just a phase changing in time. This process makes the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix of the system to decay to zero, leading inevitably to a stationary diagonal solution, so no thermalization is taking place, with occupation probabilities preserved and coherence erased. In [

30], the phase-damped oscillator to the system exhibits these features, with the specification of using the Lindbladian master equation to describe its characteristics. Here an alternative approach is proposed, which will be equivalent. As dephasing will be relevant, the mechanism devised by Milburn [

31], where the assumption that on sufficiently short-time scales the system evolves by a random sequence of unitary phase changes generated by the system’s Hamiltonian, can be thought as a suitable way of dealing with the phase damping. This process, called intrinsic decoherence, has been the subject of numerous studies since its introduction, due to the ability to handle damping in the systems. Despite the former discussion about the background of the proposal [

32,

33], and recent inquiries about the suitability of this kind of decoherence as a physical theory [

34], we can justify the election as an alternative to modeling a master equation with the Hamiltonian itself as a decaying operator [

35]. As a direct antecedent, investigations in a coupled and displaced harmonic oscillator, along a simple moving-mirror system have been done [

36–

38], but a large corpus of results exists within the literature [

39–

49]. As a final ingredient in this manuscript, the use of the well-developed non-stationary spectroscopy proposed by Eberly and Wódkiewicz [

50] is considered, which has been successfully used for many kinds of system and processes; pure atomic [

51–

53], atom-field [

54,

55], and thermalization process [

56,

57]. The advantage of capturing information about the energetic transitions and resonances in the system as a function of time is notable, and whose limit in the long-time is the well-known Wiener–Khinchin power spectrum, it then leads to a natural choice to explore the energetic setting of the system evolution in time. Notably, there have been contributions to resolve the single-photon spectra of the usual optomechanical interaction [

58], up to the linear coupling term, resulting in the formation of the well-known sidebands, providing insights on how these features arise. Conjuring the system, the pure dephasing evolution scheme and the spectroscopic visualization process, the proposal of this paper is to ask how the dynamics of an optomechanical system, with linear and quadratic couplings, experiencing a damping due to phase decoherence is presented, and also the spectral response in the evolution of the mechanical system. Particularly, the single-photon influence in the resonator is described, plus a comparison when the cavity field and the resonator are prepared initially in coherent states as well.