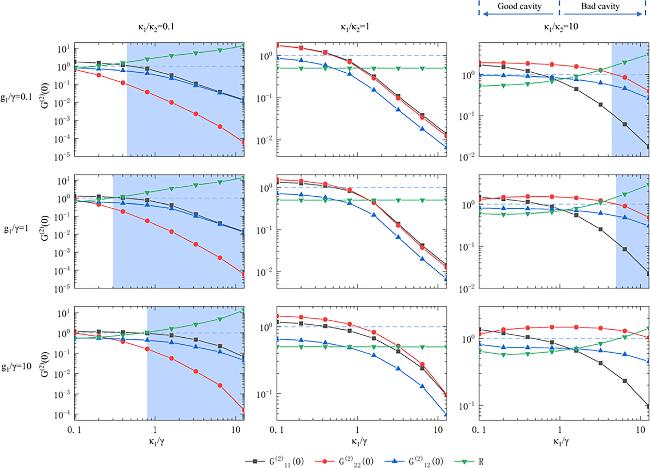

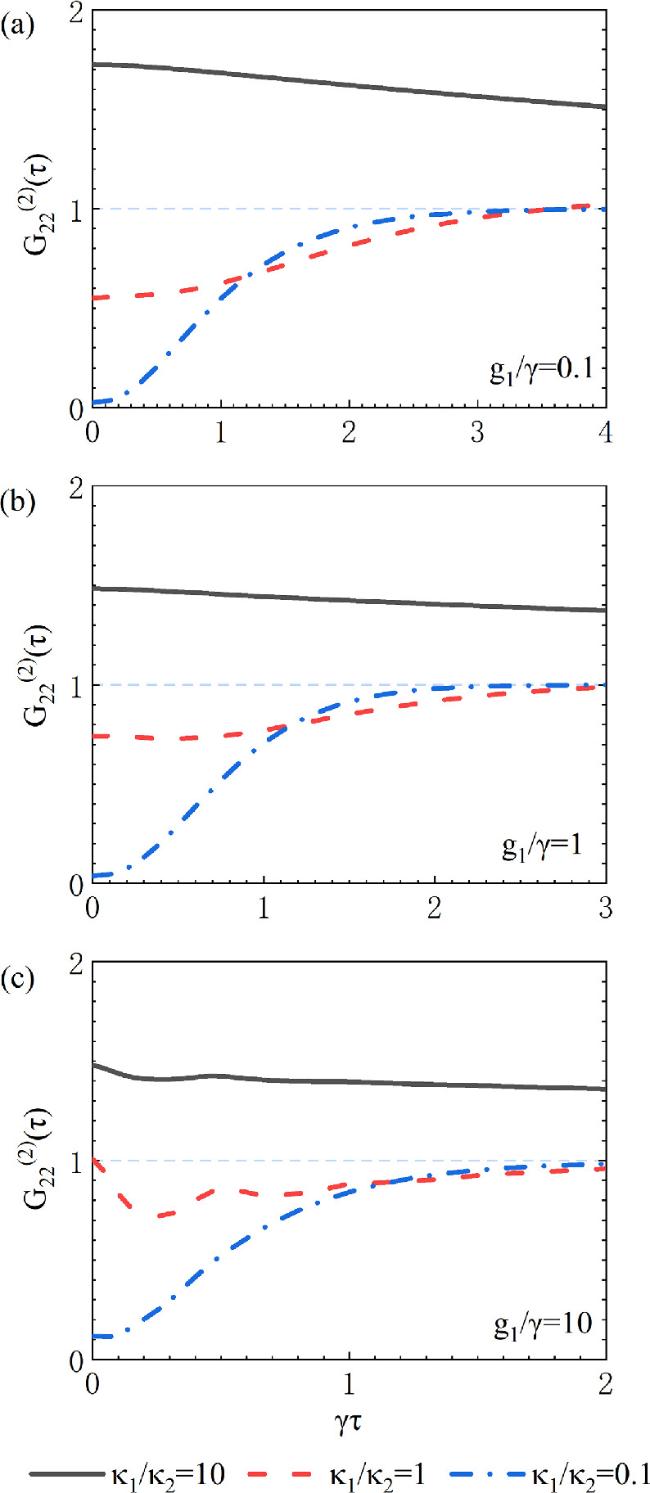

The blue-shaded region in figure

4 represents the parameter space where both

${G}_{1,1}^{(2)}(0)$ and

${G}_{2,2}^{(2)}(0)$ are less than 1 and

R exceeds 1, that is, single-field correlations and their cross field correlation all exhibit nonclassical behaviors (i.e., full nonclassicality). When

κ1/

κ2 = 0.1, the threshold point for the onset of full nonclassicality does not vary linearly with the coupling strength. Specifically, the threshold points are 0.45, 0.2, and 0.8 for

g1/

γ = 0.1,

g1/

γ = 1, and

g1/

γ = 10, respectively. Notably, the threshold point is smallest for

g1/

γ = 1, where the violation area is also the largest among all nine cavity configurations. This phenomenon is primarily driven by the behavior of the nonclassical threshold of field 1,

${G}_{1,1}^{(2)}(0)$. Its threshold point decreases initially with increasing coupling strength but then increases, showing a non-monotonic trend. In contrast,

${G}_{2,2}^{(2)}(0)$ and

${G}_{1,2}^{(2)}(0)$ exhibit minimal variations, primarily because the relatively large

κ2 reduces the influence of field 2 on the system. This also results in a lower photon number within the cavity, causing field 2 to remain in a nonclassical state throughout. Under these three conditions, the violation factor

R reaches values exceeding 13 at

κ1/

γ = 12.8, and it continues to show an increasing trend.