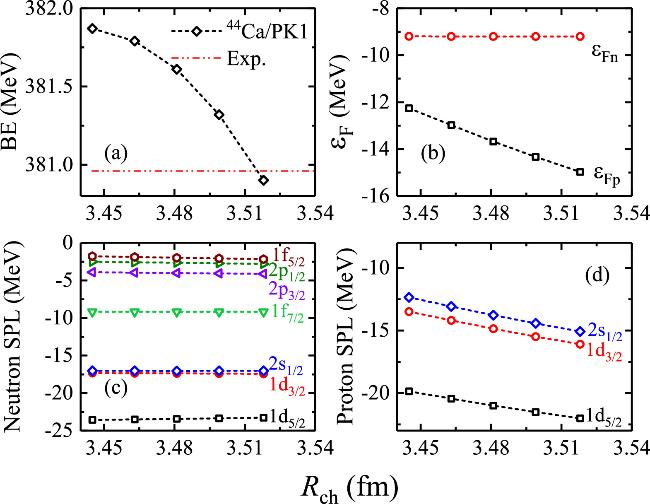

Before and after the constrained calculations, the apparent differences can be found in the binding energies, charge radii, proton density distributions, and the proton Fermi surface, etc. Furthermore, it is necessary to analyze in detail the changes of the binding energy, neutron and proton Fermi surface, shape deformation, neutron and proton single-particle levels, and the corresponding occupation probabilities with respect to the constrained charge radii. As shown in figure

4, the binding energies, Fermi energies

ϵF, neutron single-particle levels, and proton single-particle levels of

44Ca isotope are depicted as a function of the constrained charge radius with effective force PK1. From this figure, one can find that the binding energy of

44Ca is smoothly decreased with the increasing values of the constrained charge radii. Meanwhile, as shown in figures

4(b) and (c), the neutron Fermi energy

ϵFn and neutron single-particle levels (SPLs) are almost not changed with the increasing values of the constrained charge radii. By contrast, as shown in figures

4(b) and (d), the proton Fermi energy

ϵFp and proton SPLs are almost linearly decreased with respect to the target charge radius of the constrained calculations. With the increasing charge radii, the corresponding occupation probabilities are almost not changed. In addition, the absolute values of the deformation parameters

β20 are less than 0.0005. This means the nucleus

44Ca is almost spherical shape with the increasing charge radii. That is why the spherical quantum numbers are used to remark the evolution of the neutron and proton single-particle levels in figure

4, respectively.